The islands that want tourists as well as fish

Adrienne Murray

Adrienne MurrayHundreds of miles from its nearest neighbour, the remote Faroe Islands are surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean. Fishing has always been a way of life, and fish accounts for 90% of all exported goods. But coronavirus is hitting efforts to increase tourism.

The drive to the village of Glyvrar is nothing less than dramatic.

The road from the airport winds past mountains and fjords, and passes through tunnels cut into hillsides and burrowed under the sea.

Glyvrar is home to the Faroe Islands' largest firm, Bakkafrost - which farms salmon.

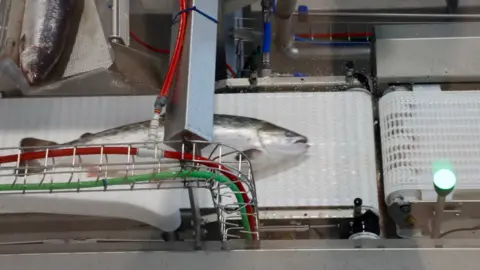

At its state-of-art plant almost 60,000 tonnes of salmon is processed annually.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe operation is highly mechanised, with conveyor belts carrying the fish through a series of machines until the finished product is packaged. Then robotic arms sort boxes ready for shipping.

From hatcheries breeding juvenile salmon to a facility making fish feed, Bakkafrost has a foot in almost every tier of the industry. Even the company's branded Styrofoam boxes are manufactured on site, characteristic of the Faroe islanders' self-sufficiency.

"We were one of the first operations here in the early '80s," says chief executive, Regin Jacobsen. "We saw that being in the middle of North Atlantic, the supplies and logistics to get our products to market were quite difficult."

But there was also opportunity, he says. "[We can] differentiate ourselves… and create high values."

Globally, farming of Atlantic salmon has soared from 1.4m to 2.6m tonnes in a decade. Norway and Chile are the biggest producers by far, but Faroese salmon commands a premium price.

Adrienne Murray

Adrienne MurrayThe Faroe Islands are located approximately 200 miles (320km) north of Scotland, and are an autonomous territory of Denmark. There are 18 main islands, and the population is just 52,000.

Its salmon typically sells for 10% more than average market price because of a number of factors. These include the use of quality fishmeal, high farming standards, sustainability and avoidance of antibiotics.

Mr Jacobsen says 15 years ago most of the country's salmon exports went to the European Union, but today it's sold around the world.

Russia and the US are the biggest buyers. In 2014 Russia banned food imports from the EU, in retaliation to sanctions against it over Ukraine. However, the Faroe Islands is not in the EU, unlike Denmark, and saw its exports to Russia grow.

Mr Jacobsen adds that sales have been boosted in recent years by the growing popularity of salmon sushi, and wider healthy eating trends.

But as the coronavirus pandemic has sent shockwaves around the world they have been felt in the Faroe Islands.

Adrienne Murray

Adrienne MurrayTotal Faroese exports fell 7% in the first quarter of this year, with sales to China falling a whopping 65% as Beijing temporarily froze many food imports.

"The Chinese market has been becoming a more and more important market," says Mr Jacobsen. "For Bakkafrost it's even more important. Around 20% of our sales are in China in recent years."

Conversely though, lockdown restrictions elsewhere have actually boosted business.

"We have very good growth both in the US and the European markets," says Mr Jacobsen. "The supermarkets have had much higher sales than normal, because people are eating more at home."

Adrienne Murray

Adrienne MurrayTo protect its population and economy from coronavirus, the Faroe Islands has one of the highest testing rates worldwide, with a strong track and trace and quarantine strategy. And every person is tested on arrival in the country.

This preparedness was partly thanks to its fisheries. A veterinary laboratory established years ago to monitor disease, was adapted early in January, ready to help test human samples.

This has no doubt contributed to the fact that the territory has reported not a single death from Covid-19. And it has seen only 227 confirmed cases in total.

Global Trade

With the Faroe Islands' economy in good shape, it's well-placed to weather any coronavirus headwinds, thinks Heri a Rogvi, chairman of the Faroe Islands' Economic Council.

"Corona has upset the economy a bit," says Mr Rogvi. "But at the present time, we have an unemployment rate of 1.7%, which is extremely low. I think we're probably the economy in Europe that's doing the best."

Led by its fish sector, which accounts for 20% of economic output, the Faroese economy has prospered. The most recent statistics show that its gross domestic product per capita (a country's economic output per person) totalled $58,950 (£45,102) in 2017. That is almost as high as the US ($59,958), and more than both the UK ($40,361) and France ($40,109).

The territory also receives an annual subsidy from Denmark of about $100m. Keen to diversify their economy the Faroese have been targeting tourists in recent years, but visitor numbers are down sharply this year due to Covid-19.

"This is the only tour we do today. There's 14 people on the boat," says Gunnar Skuvadal, as he steers his motorboat, Froyur, towards the seabird cliffs near the town of Vestamanna. He usually runs tours from April, but the Faroe Islands only opened its borders in mid-June this year.

Adrienne Murray

Adrienne Murray"On a normal day in June, we would have probably done three tours with fairly full boats, meaning about 40 people on each."

Germans, Danes and "staycationing" locals are among the passengers on-board snapping pictures of sea-caves and nesting puffins.

"If I can get through the summer without doing a minus [making a loss], I think we should be satisfied," says Mr Skuvadal.

In recent years tourism has thrived, attracting record visitors. Viral marketing campaigns like Google Sheepview, and 2019's "Closed for maintenance" campaign have put the Faroes on the tourist map.

Last year the country saw 130,000 visitors. New air routes from New York and London were set to launch this year.

"We will probably only have 20-30% of the annual visitors we were supposed to have in 2020," says Gudrid Hoejgaard, director of Visit Faroe Islands. So it will really be a horrible year. But I'm quite positive for 2021."

Visit Faroe Islands

Visit Faroe IslandsShe adds: "Tourism is still a small industry here [2% of the economy]. But it's broadening the labour market. It's created jobs in the service sector and creative area."

The hope is that this economic diversification will encourage young islanders to stay rather than move abroad. A deep recession in the early 1990s saw thousands of people leave.

Then in the early 2000s, unemployment rose sharply again when disease rocked the salmon industry. Of the dozens of salmon companies at the time, most went out of business.

"We're [still] quite vulnerable, but compared to where we were 15-20 years ago, it's much, much stronger at this time," says Mr Rogvi.

"There has been an ongoing struggle for, I think, at least 50 years to get the younger people to stay here."

Many go to university abroad, and often don't return. But with improved job and education prospects that's begun to turnaround.

Meanwhile, rising immigration, coupled with Europe's highest fertility rate, has seen the population climb to the already mentioned 52,000.

"For us that's an enormously high number," says Mr Rogvi.