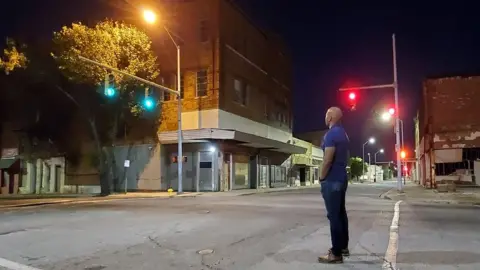

The frustration of trying to invest in my hometown

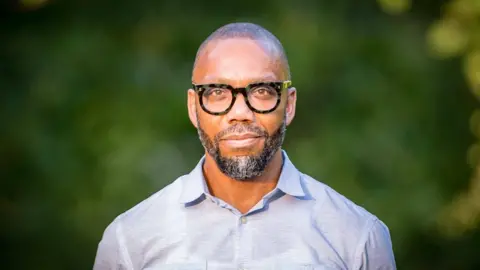

Brian Rice

Brian RiceAfter years of working in states across the US, engineer and entrepreneur Brian Rice decided he wanted to invest in his hometown of Birmingham, Alabama.

He had enough cash to buy eight buildings, all around 100 years old, in his majority black neighbourhood of Ensley, but he needed a banking loan to redevelop them. He thought it would be just a formality.

What he discovered was a system stacked against people like him.

"I thought it was the worst appraisal in the United States," he says, recalling the moment he opened the valuation the bank had given him for his properties and read its justification.

"They compared my eight historic properties to farmland 14 or so miles away, and they compared my buildings to an abandoned car wash. Nothing about my properties resembles those."

Brian Rice

Brian RiceFive of his properties were in a decent state of repair and some had sitting tenants, while three needed a complete refurbishment. He had grand plans to build apartments and restaurants, as well as exhibition spaces for local artists and incubator hubs for fledgling businesses. He wanted to make money, while supporting his neighbours and their aspirations.

By the time he received the bank's letter, he had already faced three months of stress and delays. He had approached half a dozen banks, confident that with his track record and "solid credit score", he could secure the financing within four to six weeks.

It didn't happen and Mr Rice believes the fact that Ensley is a black neighbourhood was the main factor, especially after being asked questions about the "demographics of Ensley".

One bank finally sent someone on location to assess his properties 12 weeks later. They valued the buildings at zero dollars and just over a dollar per square foot for the land only. As the rules for most banks say a property must be valued at a minimum of $50,000 (£39,000) to get a line of credit against it, his case was shut.

Brian Rice

Brian RiceDuring that process, he talked to other investors and friends in a similar position and realised his case was far from unique.

"It's one thing to do this with one building," he says, "if it is small and falling apart. It's another thing to do it with eight buildings with sitting tenants. So I said, 'It's my time to speak up and stand up.' This shouldn't happen to the next person."

Birmingham was one of the most segregated cities in the US, leading Martin Luther King to launch "Project C" in 1963, which was one of the most influential campaigns of the civil rights movement.

After a series of marches, sit-ins and arrests, Birmingham shops and businesses finally agreed to desegregate all restrooms, lunch counters, fitting rooms and drinking fountains and to hire more black workers.

But Mr Rice believes that for black residents, segregation, albeit of a different kind, is still very much a part of their lives.

"The reality is that African Americans have always been locked out of the access to capital from banks. In a lot of cases, they don't own the buildings in their communities or they just have dilapidated ones that they can't move forward with. It is pure frustration."

KATE GOWMAN/MOTORCITYKATE.COM

KATE GOWMAN/MOTORCITYKATE.COMAnd the data corroborates his real-life experience.

The Brookings Institution's Andre Perry is from the black neighbourhood of Wilkinsburg, Pittsburgh. He poured years of research into his new book, Know Your Price - Valuing Black Lives and Property in America's Black Cities.

Properties in black neighbourhoods are priced 23% lower than their equivalents in white areas, an average of $48,000 per home, he says. That amounts to about $156bn in lost equity "simply because of the concentration of black people around it, not because of education, crime, housing quality or demand. It's literally robbing people of the ability to lift themselves up".

Last year, Mr Perry testified before the US House of Representatives Committee on Financial Services looking into racist lending practices and he is calling for the reform of how valuations are done in the US.

For their part, many banks say black lives do matter. JP Morgan Chase, the largest bank in the US, launched its Advancing Black Pathways programme just over a year ago. Programme head Sekou Kaalund says the goal is to "ensure that we have as many of the 2.6 million black businesses in this country ready to receive capital and thrive".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHowever, these lofty ideals are yet to transform the banking landscape. For example, in Chicago, for every dollar banks loaned in the city's white neighbourhoods in 2012-18, they invested just 12 cents in black neighbourhoods. And JP Morgan Chase lent 41 times more money in white areas than in black ones.

Mr Kaalund recognises these results as "disappointing", but stresses that a systemic change is needed if things are to improve for black entrepreneurs and prospective and current homeowners.

He says his bank's Entrepreneurs of Colour Fund highlighted that these borrowers would not have been able to get a loan from any bank. "Your models would have said these borrowers wouldn't have paid you back. They don't have the collateral."

He thinks there is an opportunity to evaluate how lending risk is assessed, but there are challenges.

"When the Federal Reserve examiners come in, and you are making loans that are deemed lower credit quality, then the amount of capital you need increases. So it's not just one lever and that's the banks. It's going to be the system."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome say investing in black-owned banks is one solution to this problem of undervaluing black assets and access to funding. Streaming giant Netflix has recently said it will put 2% of its cash (about $100m) into black-owned financial institutions.

Netflix bosses cited the book, The Colour of Money, Black Banks and the Racial Wealth Gap as the inspiration for this. Yet its author, banking law professor Mehrsa Baradaran, is not so sure that black banks can by themselves right historical wrongs.

"Repeatedly, we've used these soft and anaemic solutions to these massive problems. If you combined assets of all the black banks - and it's only 20 black banks in this country - that's a bad weekend for Citibank," she says.

In 1863, when President Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, black Americans owned less than 1% of US total wealth. Nearly 160 years later, this number has barely budged.

Mehrsa Baradaran

Mehrsa BaradaranProf Baradaran says one key part of solving this is financial reparations, which would put black people in the place where they would have been, were it not for racially discriminatory laws over hundreds of years.

She also wants lawmakers to consider something like a public banking system - akin to those in Europe or China - in areas which might not be profitable in the current system dominated by a handful of banking giants.

While financial institutions and academics are trying to find ways of addressing racial economic inequality, in Birmingham, Brian Rice is still without funding for his development project.

His voice breaks as he talks about friends who support him and why he still keeps knocking on doors, looking for funding.

"The greatest challenge for African Americans is access to resources. If unfair banking is removed from my story, all of my eight historic buildings would be renovated and there would be thriving businesses in them that improve the community.

"It's really operating from hope, dreams and that no give up spirit right now."