Intu collapse: What went wrong for the retail giant?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShopping centre giant Intu has entered administration, placing thousands of jobs in doubt.

But there have long been problems at the firm, which sought help with its debt in January.

What went wrong at Intu, which was one of the UK's biggest shopping centre group?

Debt piling up

Intu had been struggling even before the coronavirus outbreak.

One area of concern for potential investors is Intu's £4.5bn debt, given the declining value of its shopping centres, which will stay open under administrators KPMG.

They "just aren't worth the value they once were", retail expert Kate Hardcastle told BBC News.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe value of its the centres it owns fell by 22% in 2019 to £6.6bn. The company also posted a £2bn loss for that year.

The firm, which owns the Trafford Centre, the Lakeside complex and Braehead, also has a "very complex infrastructure" at its heart, Ms Hardcastle said.

Another shopping centre owner might use a separate services company to run operations, such as cleaning, security or its car parks. But "at Intu, there's a web of companies involved in the organisation", she said.

Retailer woes

Shopping centre landlords such as Intu rely on big retailers for their revenues.

But in recent years, stores have been asking landlords for rent reductions due to the pressures they are under, Ms Hardcastle said.

The coronavirus lockdown imposed by the government on 23 March has meant that rent collection fell even further for retail landlords.

Shop landlords typically collect rent on a quarterly basis. But when UK retailers had to pay rent for the three months to 29 September this Wednesday, just 14% of the £2.5bn due was paid, according to property data company Re-Leased.

"The old relationship was quite adversarial between landlords and tenants," says retail analyst Richard Hyman.

"That's not going to work anymore. Everyone is going to have to take the pain, and it's always best to share it."

Changing habits

"In many ways, the pandemic is an accelerator, and will really have forced change that would have taken five years or more to happen now," Mr Hyman told BBC News.

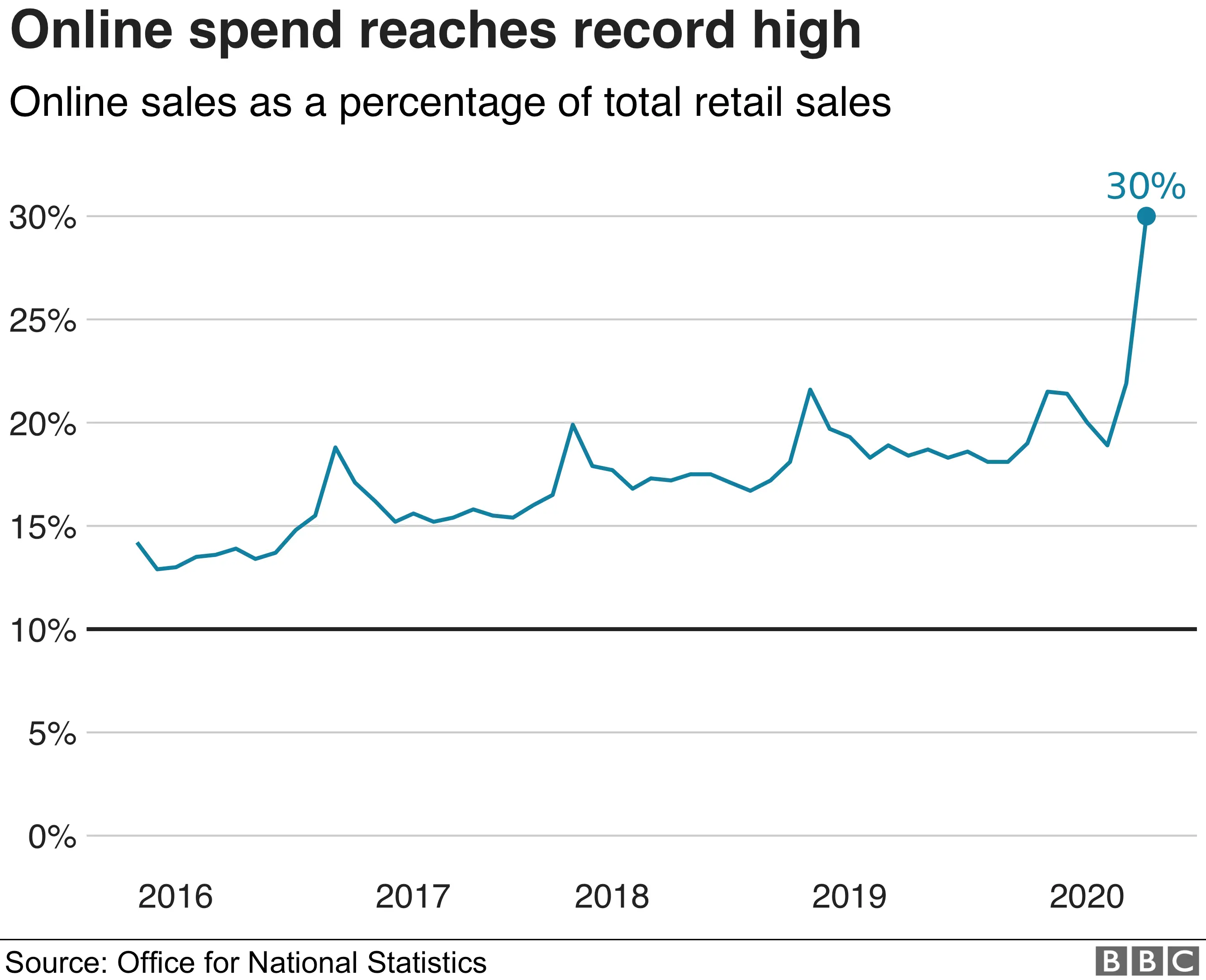

Although the proportion of spending online had been increasing steadily, it reached new highs during lockdown.

Online sales rose to their highest proportion on record in May while consumers stayed at home. They accounted for 33.4% of total spending, compared with 30.8% in April, according to the Office for National Statistics.

With the "turbo-charge of online", shopping centre owners such as Intu need "to understand that they no longer have the monopoly on bringing the customers and the retailers together", Mr Hyman said.

"Millions of people in Britain have been shopping happily in lockdown who've never done it before, and a lot of people will change their behaviour as a result."

Regeneration challenge

The collapse and contraction of large retailers in the face of rising costs and the ever-increasing online shopping trend had already seen retailers closing outlets.

That left a number of landlords, such as Intu, struggling to fill empty space as conditions get tougher.

Kate Hardcastle points out: "We've seen in other shopping centres replacing those big units with offices or gyms, but Intu don't have those relationships - it is pretty dependent on retail."

She argues that it could be time for its "glossy infrastructure" and large units to be repurposed.

"Intu have come in and created something quite sterile, without a celebration of its placing... Now they're relying on those communities to keep them going."

But she added that the outlook could be gloomy for the shopping centre giant as it appoints administrators.

"This isn't a typical trading market. Rents not being paid fully which isn't enticing, consumer confidence is low and we are facing one of the greatest economic challenges of our time ahead."