Coronavirus: The shops refusing to pay their rent

BBC

BBCAndrea Orsini's family has run M Bar in London's Leadenhall Market for 40 years.

But after shutting up shop because of the lockdown, he says he can't afford his next rent bill.

He pays £70,000 a year to his landlord. On top of that, he must also fund a service charge, business rates and a tables and chairs license.

It all adds up to £125,000 which, as he puts it, is a lot of tea and coffee.

Round the corner, Patrick Dudley Williams, who runs the clothing brand Reef Knots, is in a similar position.

He said it would not be sustainable to borrow money to fund rent for his shop, which is currently closed and in a part of the city that is unlikely to see customers return for some time.

Their landlord, the City of London Corporation, says it is aware of the difficulties faced by businesses in Leadenhall Market.

The corporation, which is the local council for the Square Mile, said it has offered three month rent deferrals to selected tenants, adding that it was considering further support.

Can't pay, won't pay

A similar story is being told up and down the country.

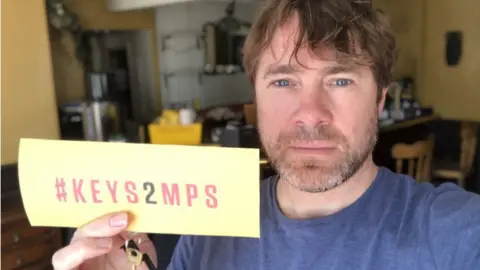

This weekend, Cheltenham publican Ed Anderson handed over his pubs' keys to his local MP to highlight the difficulties that businesses are facing paying rent while they are closed.

Ed Anderson

Ed AndersonHe says rent bills will "break" the hospitality sector and he's encouraging other business owners to join his campaign Keys2MPs.

Since the lockdown, non-payment of commercial rent has become widespread

Michael Old, a partner at EY, said the biggest drop in rent collections had been in the retail, hospitality and leisure sectors.

He said retail landlords had collected less than half of rent due in March. "This compares to 66% in the office sector and 83% in the industrial sector," he said.

He expects to see a further decline in rent collection levels in June. And that's a major problem for landlords who have their own financial obligations.

Changing the locks

The Coronavirus Act has temporarily banned landlords from evicting tenants if they don't pay their rent.

In the more constructive cases, landlords are deferring rent payments or changing them to monthly instalments - sometimes in arrears.

Nick Ridley from Cushman & Wakefield, a commercial real estate firm, says landlords have been taking a harder stance when they think companies are using the crisis as an excuse not to pay - especially when it comes to larger chains and companies such as pharmacies that have remained open.

"My investment fund clients are starting to weed out the genuine hardship payments from the opportunistic tenants," he said.

Lawyer Vicky Khandker, who works at Lodders, says landlords and tenants need to work together to address the issue of where the rent bill should land.

Vicky Khandker

Vicky Khandker "Ultimately, landlords don't want to find that, at the end of this, they've suddenly got a lot of their tenants that simply no longer exist and haven't survived - because they'll be left with a glut of empty properties".

Companies are complaining that some landlords are unwilling to engage.

The owners of pub and brewer BrewDog say that, of their 60 UK landlords, a third have not been willing to communicate and "less than 10% have done anything that offers meaningful help so far".

Large chains such as Burger King UK are refusing to pay their rent until they are properly back in business. This has resulted in a couple of winding up orders, but they have otherwise had a constructive dialogue with their many landlords.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhen it comes to the landlord-tenant relationship, there's no one size fits all model.

While the tenant may be the most visual victim of a demand for rent - that's not always the case.

Professor Andrew Baum from the University of Oxford explains that landlords are not always the more powerful party in the relationship. "The landlord of a property might be a pension fund paying the elderly, and the tenant could be a private equity-owned business," he said.

Ms Khandker agrees. "In some cases, landlords may be much smaller businesses than the tenants that occupy their premises, so the landlords may be left in a much more severe position than the tenants are," she said.

Campaigns for change

The government says it recognises the huge challenges being faced by commercial tenants and landlords during this period. "We're working closely with them to ensure they are supported and would urge landlords and tenants to follow the example of others and find solutions that work for both parties," it said.

Hospitality businesses, led by restaurateur Jonathan Downey, are running a campaign called National Time Out, calling for a nine-month rent holiday, meaning leases are extended and payments postponed to the end of the tenancy.

The retail property association Revo, in conjunction with the British Retail Consortium and the British Property Federation, would like to see a "Furloughed Space Grant Scheme", effectively calling on government to underwrite rents for stores that are closed.

Vivienne King, chief executive of Revo estimates around a third of rent was paid for the second quarter of the year.

"In the majority of cases retailers and property owners are working together to navigate this crisis," she said.

"However, the flexibility shown by both sides is not sustainable in the longer term, and there is a real risk the ecosystem built upon on thriving occupiers could collapse unless there is direct financial support from government."

Professor Baum does not believe this is a viable solution. "It would be such a dangerous game to play - what happens to a retailer paying dividends but not their rent," he asks.

"What about future profits? And why haven't businesses saved for a rainy day?"

Until then, it is up to landlords and tenants to make their own arrangements about where the bill should fall.