Who are the millions of Britons not working, and why?

BBC

BBCIn the Spring Statement, Chancellor Rachel Reeves is announcing a series of measures to cut the welfare bill by making it more difficult for people to claim certain benefits.

The hope is that this will "get Britain working" by incentivising some of those not working to rejoin the labour force.

About a quarter of the working age population - those aged 16 to 64 - do not currently have a job. That's about 11 million people.

How many people are unemployed?

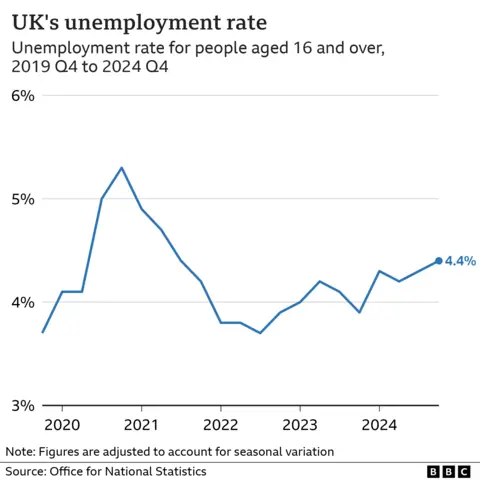

According to the latest figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS), 4.4% of people were unemployed in the period between October and December 2024, which is about 1.6 million people.

While this figure has risen over the past two years, unemployment remains relatively low by historical standards.

However, unemployed people represent only a small part of the nearly 11 million working-age people who don't have a paid job.

About 9.4 million of them are not called "unemployed". That is because they are not actively looking for work, or available to start a job.

Instead people in this group are called "economically inactive".

But 1.6 million of that group - in addition to the unemployed - do say they want a job.

The number of vacancies is currently just 0.8 million - that has been falling consistently for the past two years, with a slight uptick in the latest figures.

Who isn't working - and why?

It varies according to age.

ONS figures for October 2023 - September 2024 show that most of the 2.8 million "inactive" under-25s were students. The majority of them did not want a job.

You can see that in the graphic below. Click on the darker border surrounding any age group to see their reasons for being out of work.

Things are different in other age groups.

Among 25- to 49-year-olds, nearly 1.1 million people did not work because of caring responsibilities, nearly a million of whom were women.

Over one million people in this age group were not working because of illness.

The main reasons that 3.5 million over-50s were out of the job market were illness and early retirement. Very few of those who retired early said they wanted to return to work.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAround half of people with disabilities did not have a paid job, a rate that is more than double the rest of the working-age population.

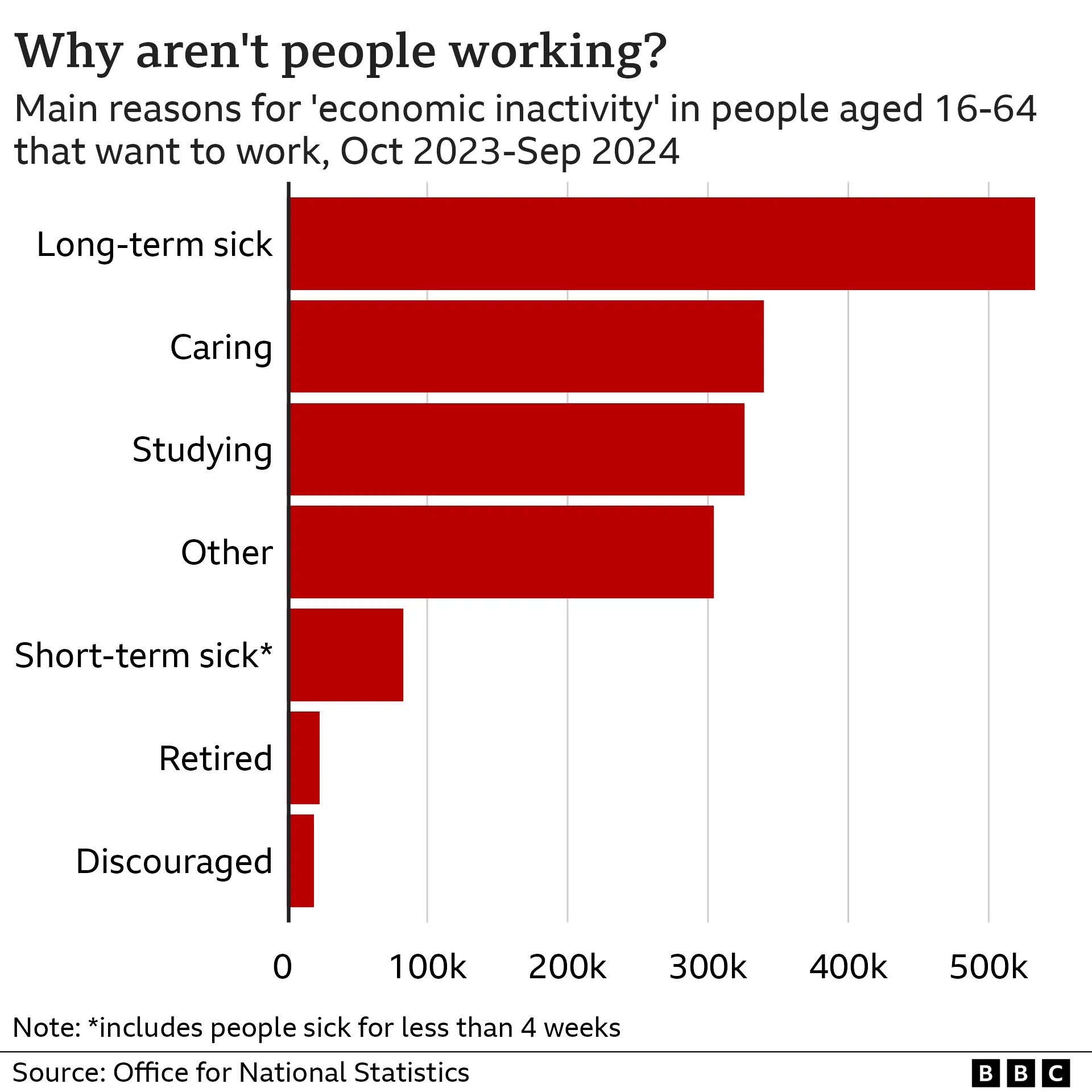

Less than a quarter of all those who were sick or caring said they wanted a job.

Does it matter that people aren't looking for work?

Many people are not looking for work because they are studying, caring or have retired.

Some people want to work but cannot, either because childcare is too expensive or they are not well enough.

As the chart below shows, caring responsibilities and ill-health are the most common reasons for inactivity given by those who would like a paid job.

The number of people not working has a broader effect.

A smaller workforce means the government raises less income tax and National Insurance, which it uses to pay for services like the NHS.

It may also spend more on benefits.

Since people on benefits generally have less money than those in work, it also means less spending on the High Street.

That in turn is bad for businesses, and can affect how many people they employ, which can mean there are fewer jobs for those who do want to work.

How does the UK compare with other countries?

During the Covid pandemic, all major countries saw their workforce shrink.

But while many other leading economies have since recovered, the UK still has more people out of its workforce than it did in 2019.

There is a debate about how much of this is down to problems with how we work out how many people are inactive.

Before Covid, the UK's "inactivity rate" was the second lowest in the G7 club of leading economies, behind Japan.

The increase in the inactive population since then means that now the UK has a higher inactivity rate than Japan, Canada, and Germany.

The independent Office for Budget Responsibility - which assesses how well the UK economy is doing - has suggested that ill-health has consistently been a bigger factor in the UK than in other advanced economies.

What is the government doing to get more people into work?

Last week, the Work and Pensions Secretary Liz Kendall unveiled a series of welfare reforms that would make it harder for people with less severe conditions to claim disability payments.

The stricter tests for personal independence payments (PIP) are expected to affect hundreds of thousands of claimants.

Extra benefit payments for health conditions will also be frozen for current claimants and nearly halved for new applicants while people aged under 22 could be prevented from claiming Universal Credit (UC) top-up payments for health conditions.

In her Spring Statement, Chancellor Rachel Reeves added that health-related UC will also be frozen until 2030.

This is all in addition to the November plans, announced by Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer sto get two million more people into work.

The proposals included:

- overhauling the health and disability benefits system to better support people to get jobs and stay in work

- rebranding job centres as the National Jobs and Careers Service

- offering every 18 to 21-year-old in England an apprenticeship, training or education opportunities or help to find a job as part of a new "Youth Guarantee"

- an independent review of what UK employers are doing to promote health and inclusive workplaces

- providing more money for the North East, South Yorkshire and West Yorkshire to stop people leaving work because of ill health

- expanding mental-health support and efforts to tackle obesity.

The proposals followed widespread criticism from businesses that the increase in National Insurance announced in the Budget, coupled with the rise in the minimum wage, will make it harder for them to create new jobs.

Companies warn this will undermine the government's goal of increasing the working population.

Data visualisation by Aidan McNamee.