Coronavirus: 'We feel so lost' - Young face job despair

Jared Thomas

Jared ThomasJared Thomas says he is trying to inject some excitement into his life by getting into the kitchen and cooking something nice.

The 26-year-old is hungry for work, but the coronavirus outbreak means financially stretched customers have little appetite for his tree surgery services at the moment.

"Everybody's life has been turned upside down," he says.

"I really don't know when work will pick up. I'd be surprised if it does for the next month or two."

Like so many other young employees, it may feel that he has been forgotten in this economic crisis.

Jared, from south Wales, says he started this work too recently to be eligible for the government's financial support for the self-employed. Instead, he has claimed the universal credit benefit for the first time, so he can pay the rent.

In many ways, he is still one of the lucky ones. If work picks up, he still has a job.

That is not the case for Jemma, a 16-year-old from Fleet, who was let go from a salon during her hairdressing apprenticeship.

No job means no qualification which, she says, has left her "heartbroken".

She is too young to drive, and the chances of finding another job nearby are looking increasingly slim.

"They will be so focused on building up a salon, they will have no time to take new people on," she told the BBC's Newsbeat.

"I don't know what to do anymore."

Young people like her may feel "so lost" even after the virus fades, she worries about their mental health.

Lessons from the past

History shows that school leavers like her are usually hardest hit following a recession in terms of financial health too.

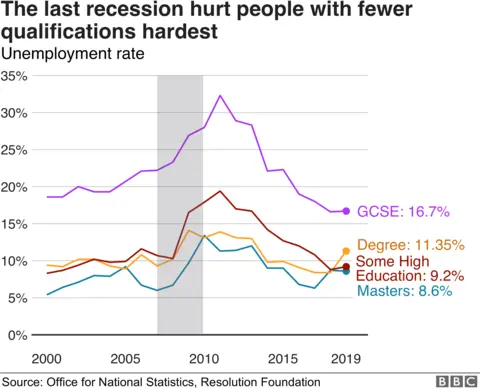

Many suffer longer spells of unemployment, and slower pay rises, than people with degrees.

For example, unemployment among students with GCSE-level qualifications peaked at 32.3% in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, official figures show.

This compares with 13.4% for those with a masters degree.

There could be more than one million young workers who are without a job, if the overall UK level of unemployment goes up from the current 4% of workers to 10%, according to the Resolution Foundation think-tank.

For lower-skilled young adults, it believes the chances of getting a job will be reduced by a third. For recent graduates, it will be down by 13%.

Kathleen Henehan, a research analyst at the Resolution Foundation, says many graduates "traded down" into jobs in retail, hotels and the travel industry during the last financial crisis.

This forced some school leavers into part-time work and jobs where they were less likely to be promoted quickly.

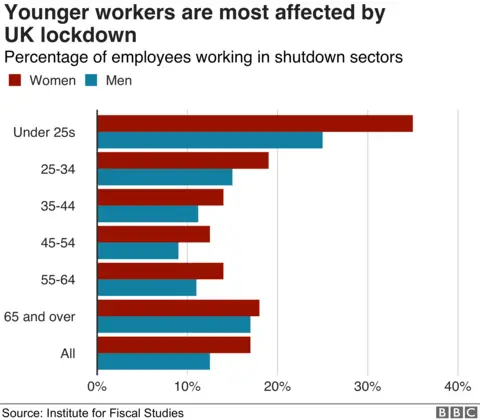

But Ms Henehan says many of these sectors are now shut down, leaving everyone with fewer options.

"In other words, the first rung of the employment ladder looks to be broken," she says.

Experts say the government should renew its focus on entry-level training.

The number of apprentices who are under the age of 19 has continued to fall.

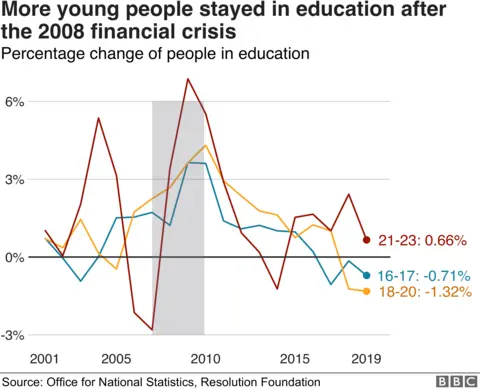

Ms Henehan says one way young people can ride out this crisis is to stay in school or further education.

For example, the number of 21 to 23-year-olds in further education rose by 7% between 2008 and 2009.

Ms Henehan expects a similar pattern this year, and is urging the government to provide more financial support for school leavers wanting on-the-job training.

Recent research also suggests young people will live with their parents for longer to help cushion any financial blow.

Around 61% of under-25s who work in shutdown sectors currently live with their parents, according to economists at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

University students expecting to graduate soon are also scratching their heads over what to do next.

The negative impact on job prospects and pay can last for years, with unlucky graduates suffering a permanent hit to incomes, according to one American study.

Meanwhile, a survey by website Save The Student found that 77% of third-year students, and 74% of those in their fourth year onwards, are worried about their graduate job prospects as a result of the effects of the coronavirus outbreak.

Among them is Adele, who is studying global media and communication at the University of Warwick.

The 22-year-old had hoped to steal a march on other job candidates by studying for a Masters, but now sees her friends who left last year in a job, while she is less confident.

Adele

Adele Jobs she applies for either no longer exist, or the companies have stopped recruiting during the crisis. Letters go unanswered and job adverts are out of date.

"It is all in limbo," she says.

"It is frustrating when you are applying for a sector that is already competitive. It will be even more so, if no new jobs are available."

Instead of living with friends and in a new job in London, she says she may have to live with her parents and work part-time in Edinburgh.

Additional reporting by Kirsty Grant

- LOCKDOWN UPDATE: What's changing, where?

- EXERCISE: What are the guidelines on getting out?

- AIR TRAVELLERS: The new quarantine rules

- A SIMPLE GUIDE: What are the symptoms?