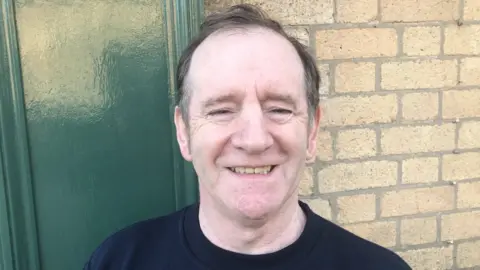

The 63-year-old apprentice learning a new trade

Former fisherman Gerry Thompson knows a thing or two about dangerous work.

"I've seen a lot of bad accidents at sea," he tells me, in Hull. "I've seen three men die. I've seen a guy lose his arm."

His fishing job gone, he is retraining in another sometimes risky industry. He finds himself an apprentice docker aged 63.

Mr Thompson says: "A lot of pride goes with it. At least you've got a certificate at the end of the day."

Bringing his lifetime of experience to the docks, he is being trained in modern health and safety. His enthusiasm is infectious.

His boss though, John Daniels of Precision Stevedores, is much less cheerful. He would like to take on 40 apprentices like Mr Thompson. But a new government system in England means he can train just three.

He says: "With the government changes, we're never going to achieve the kind of headway we're looking for."

The three-person limit for companies using a new digital apprenticeship system is temporary, the government says. If those companies can find colleges or training firms with existing contracts and spare places, they can take on more apprentices.

But Mr Daniels cannot do that. The course he needs is much too specialised.

His problem is part of a much bigger story. New apprenticeship rules introduced in 2017 see big businesses pay a levy, some of which is shared with smaller firms.

Many big companies are investing more in their staff, but that means there is less money left over for apprenticeships elsewhere.

With apprenticeships costing more than expected, in the words of the National Audit Office, "there are concerns about the long-term sustainability of the programme". That is an auditor's way of warning the money could run out.

'More and more problems'

Since the reforms, the number of new apprenticeships in England has dropped.

Mark Dawe, chief executive of the Association of Employment and Learning Providers, says: "What we have done is create a system that has removed the very apprenticeships that are needed."

Meanwhile, English further education colleges that deliver much of this training struggle to recruit after years of low funding.

Croydon College's principal Caireen Mitchell says: "We're having more and more problems recruiting specific areas such as plumbing and engineering, or even health and care, because the comparative wages are so low."

If further education colleges got the same attention as sandstone ones at ancient universities, this would be a bigger row.

So what changes now, those in the training industry ask, with a government that has promised to "level up" and create a high-skill economy?

They say that a little louder now with a Budget on the way.

People are lobbying hard to get a little more cash from an administration that has pledged a £3bn skills fund. Take the complaints of colleges and the training industry at face value though, and much of the £3bn could be needed just to shore up the current system.

Sources say budget negotiations are still going on. But many in government are hopeful that there will be more money for further education.

"There is massive will behind this," says one.

The appointment of a prominent supporter of further education - crossbench peer Alison Wolf - as a Number 10 advisor is significant.

A Department for Education spokeswoman said: "The apprentice levy means more money is available than ever before for employers of all sizes to invest in training and this year we have increased investment to over £2.5bn, double what was spent in 2010-11 in cash terms."

Meanwhile in Hull, sixty-something trainee docker Gerry Thompson is full of faith in apprenticeships.

He says: "There's always jobs on the docks for everybody. On the docks it's all hands-on. Someone's got to go on board that ship and unload it. It doesn't unload itself."

Some in this government are thoroughly sick of the demands of lobby groups, but they might find both Mr Thompson's optimism, and the political risk of ignoring workers like him, rather harder to ignore.