Protecting whales from the noise people make in the ocean

Ailbhe Kavanagh

Ailbhe KavanaghThere is a rising din in the oceans - and whales are having to struggle to compete with it.

"They're spending more time or energy trying to communicate… by essentially screaming at each other - what we would have to do at a nightclub," explains says Mark Jessopp at University College Cork.

Dr Jessopp was recently involved in a research project to study the effects of marine seismic surveys on animals such as whales and dolphins.

He and his colleagues found a "huge decrease" in sightings of such species when the work was going on, even when accounting for other factors such as weather.

Tom Hart

Tom HartSeismic surveys are carried out by a range of organisations, including oil and gas companies, as a means of mapping what lies beneath the seafloor.

Shockwaves fired from an air gun - like a very powerful speaker - are blasted down towards the seabed. The waves bounce off features below and are detected again at the surface. The signal that returns reveals whether there is, for instance, oil locked in the rock beneath.

The process creates a tremendous racket. "It's like an explosion," says Lindy Weilgart at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia. She says that there is now plenty of evidence to show that many marine animals are negatively affected by the clamour.

Ian Wilms

Ian WilmsThe effects aren't just felt by mammals like whales and dolphins, she adds. Fish and invertebrates such as crabs have also been seen to change their behaviour when noise levels rise. They can be put off feeding or become less able to detect predators, for example.

And yet a technology exists that could be far less harmful. It is called marine vibroseis and is a low-energy alternative to air guns. Instead of explosive blasts, vibroseis uses smaller vibrations to transmit waves down to the seabed. It actually emits a similar amount of energy overall but spreads it over a longer period, meaning the survey has a less "shocking" impact.

Stephen Chelminski, who invented the seismic air gun in the late 1950s, has become a proponent of vibroseis because of its perceived environmental benefits.

Dr Weilgart says there are many efforts to commercialise this quieter tech but she is unimpressed with how they are progressing. "It's just creeping along at a glacial pace," she says.

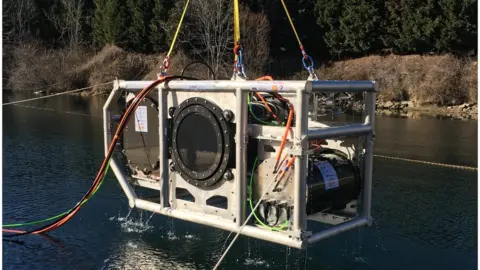

General Dynamics

General DynamicsThree of the world's biggest oil companies - Shell, Total and ExxonMobil - have spent years developing a marine vibroseis device. Andrew Feltham, a geophysicist at Total who works on the project, says that the system has been shown to function as intended but requires some further testing before it can be used in field work.

He says that one benefit of the prototype device is that it doesn't produce noise across a wide range of frequencies.

"We only emit energy within the frequency band of interest for the job at hand," he explains. This reduces the number of sea creatures that would hear noise generated by the device, lowering the environmental impact further.

Norwegian firm Petroleum Geo-Services (PGS), which helps oil and gas companies find offshore reserves of fossil fuel, has also been working on a vibroseis system. It has a different, more compact design that uses a stack of plates to generate vibrations.

Ailbhe Kavanagh

Ailbhe KavanaghThis allows for the production of a strong seismic signal but stops the device shaking itself apart.

"Using stacked plates is an ingenious solution," argues Bard Stenberg, a spokesman for PGS.

The prototype has endured a 1,000-hour test in a water tank and depths of 60m (197ft) in a harbour. However, it is yet to be trialled out at sea.

Nathan Merchant is a bioacoustician at the UK's Centre for Environment Fisheries and Aquaculture Science (Cefas). He says that vibroseis would actually be a better technology for organisations seeking to survey the seabed because it can be more finely tuned. And yet, commercial interest in it has not really materialised.

"This is one of the areas where we need a bit of a push from the policy and regulation side to create a market for that kind of technology," he argues.

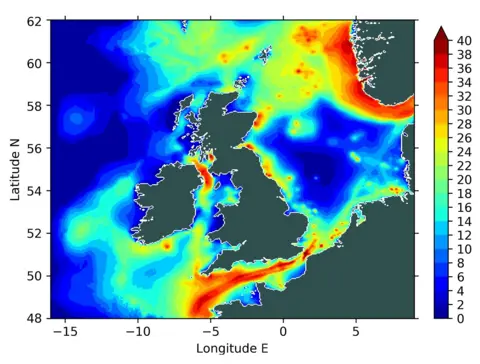

Cefas & Adrian Farcas

Cefas & Adrian FarcasDr Merchant studies noise levels in the seas around the UK. He and his team recently produced a detailed map of where the cacophony is greatest. However, while it is difficult to confirm exactly how noise levels have changed in recent decades, he says they have probably increased overall.

"The answer to that is almost certainly 'yes'," he says.

He points out that there are other significant sources of noise pollution at sea. These include noise from shipping, where, for example, propellers slicing through the water create a wake and with it a mighty rumbling sound that can travel for hundreds or even thousands of kilometres.

Then there are offshore wind farms, which rely on pile-drivers that bash huge columns into the seabed to create the base platform for turbines. Engineers on such projects also occasionally have to clear unexploded ordnance left behind, for instance from World War Two.

Detonating a bomb underwater creates a lot of noise but the bang can be softened by using a device to create a curtain of bubbles around the bomb.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWind farms in the UK licensed to use bubble curtains for this purpose include Hornsea One and Two off the north-east coast. Currently under construction, the full Hornsea complex will eventually form the largest offshore wind installation in the world.

Marine biologists continue to hope for technologies that will make human activity in the oceans quieter. Dr Jessopp acknowledges that seismic air guns are cheap and have been proven to work. With marine vibroseis still not available at a commercial scale, firms may not see any reason to change how they do things.

"In the absence of any real viable alternative we've just kept doing it. It's kind of business as usual," says Dr Jessopp.

So the seas will remain noisy for sometime and whales will have to continue to shout to be heard.