Can old fridges be recycled to make new ones?

As a result of Black Friday many old fridges will be replaced. But what happens to your old fridge, which by law must be disposed of by an approved contractor? Dougal Shaw went to the UK's largest fridge recycling plant to find out.

It's like a graveyard for fridges.

They are stacked up in columns about six appliances high and this arrangement forms a maze around the industrial site.

If you've got rid of an old fridge in the past few years, there's a good chance it's ended up here.

The AO Recycling plant in Telford receives 700,000 fridges every year - almost a quarter of the UK's total.

The peak season is summer, when fridges tend to fail and get replaced. The other spike is around Black Friday, when many people decide to replace their white goods, if they sniff a deal.

The fridges arrive from AO.com's own customers, but also from other retailers and councils.

It's been law to dispose of fridges through an approved contractor since 2002 - not least because of the greenhouse gases they contain.

Sort then smash

Appliances at the plant are first vetted to see if they were retired too early - could they be repaired and resold?

If not, their compressor is stripped out. This contains the motor and pump, as well as the refrigerant, the substance which flows around fridges to keep them cool. This needs to be extracted, as it is potentially harmful to the environment.

Then a conveyor belt will tip the fridges into a machine known as Bertha, eight at a time.

Bertha is the size of a two-story house and you can't see what goes on inside her.

First oxygen is sucked out in a sealed chamber so that further greenhouse gases can be recovered from the fridges' insulation foam.

Then the fridges fall into another chamber where huge metal chains, like the kind you see holding ships at the docks, whip the white goods at 500 revolutions per minute.

This beating reduces them to shreds of plastic and metal, which machines can then separate.

However, this rather crude material does not have great potential for recycling - it can only be used to make a few items, like seed pots for plants, for example.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSo at the moment the final resting place for old fridges may well be in your garden, or perhaps an allotment.

'The holy grail'

The vast majority of new fridges are manufactured from virgin polymer, derived from crude oil, a dwindling natural resource.

This is partly because much of the plastic used in fridges needs to be "food grade" to meet safety standards - but also, manufacturers don't want to risk the slightest imperfection creeping into their vast production lines, which run on tight profit margins.

Virgin polymers might not be good for the environment, but they are a tried and tested way of getting high quality plastic.

"The holy grail," explains John Roberts, founder and CEO of AO.com, "is to add the material recovered from the old fridges back into the supply chain once again, to make new fridges."

This is why his company has just opened a new factory five minutes' drive from the Telford recycling plant, to see if high quality, food-grade plastic can in fact be recovered from old fridges.

The new production line is about half the length of a football pitch.

A series of machines tries to whittle down the crude fridge waste to recover just the pure, single polymer, food-grade white plastic they want.

Water tanks sift out the denser materials, like metals, which sink.

Electrostatic machines can separate the various types of plastic in the mix.

An optical machine is also used to sort material by colour - the same kind of machine used in peanut factories for quality testing.

What comes out at the end of this process are pellets of white plastic, of high purity.

However, they are not yet quite pure enough - each batch is tested and so far the results are in the very high 90s - but not quite 100% food-grade quality plastic.

A manufacturer's view

If the technique is perfected, is there an appetite to turn fridge recycling into what's known as a circular economy - feeding the old fridge material back into the supply chain?

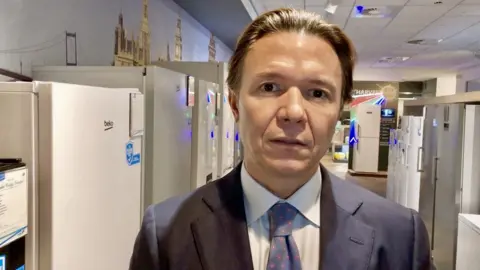

The mood of manufacturers might be changing, according to Hakan Bulgurlu, chief executive of Arçelik, the global white good manufacturers who own fridge brands like Beko and Grundig.

His company manufactures more than 18 million new fridges every year.

In the past his marketing teams and engineers would tell him that customers want pristine fridges made of virgin polymers, says Bulgurlu. They told him people would dislike the idea of fridges made from recycled materials.

That perception is now reversing, he thinks, as manufacturers realise there is public appetite for white goods that wear their environmental credentials on their sleeves, even if these products cost slightly more.

His company tries to use recycled plastic in its production line, he says, but it is a challenge with fridges in particular, because the parts of them which come into contact with food need to be made from food-grade plastic.

By contrast, they have already managed to make a vacuum cleaner that is made of 90% recycled plastic.

Beko is investing in bioplastics, made from corn husk, which don't use crude oil and can biodegrade, says Bulgurlu. So far they have made one fridge where 25% of its plastic is sourced this way.

The real holy grail, he says, "is a fridge that you can bury and two years later it has disappeared".

Follow Dougal on Twitter: @dougalshawbbc