When to fire the boss: A tale of three sackings

Getty Images / Reuters

Getty Images / ReutersThe names of some business leaders are so closely associated with the companies they run that it's almost unthinkable the firm could exist without its boss.

It's as hard to imagine Facebook without Mark Zuckerberg as it is to think of Virgin without Richard Branson.

The now-former boss of WeWork clearly counted himself among that class when, in August, his firm told potential investors: "Our future success depends in large part on the continued service of Adam Neumann, our co-founder and chief executive officer."

The firm described him as "critical to our operations" as it warned that Mr Neumann did not have an employment agreement with WeWork and said his departure would significantly hurt the business.

But, just months later, the firm - which was valued at nearly $50bn (£39bn) earlier this year - has pushed Mr Neumann from his board seat, demoting him to the role of "observer", as it agreed to a rescue package from investor Softbank that valued it at just $8bn.

Nevertheless, Mr Neumann has walked away from the firm with a $1.5bn payoff.

He is one of many entrepreneurs who have struggled to steer the ship as their companies grew from fledgling start-ups to corporate giants.

Some people - such as Alibaba founder Jack Ma or Bill Gates, who built Microsoft - have made it look easy.

But tech strategist Flavilla Fongang says that in start-up phase, new firms can focus just on growth, raising investment and building infrastructure.

Once the business is up and running, however, the founder has to turn his or her attention to more delicate tasks, such as cultivating new leaders who can run the company as well or even better, she says.

She describes firms like Uber as "very strong-minded in terms of the disruption they wanted to create" and its employees as people who "wanted to be part of that history".

"It becomes a bit of a cult almost where people come to work with a feeling that everything they do will make an impact in society," she says.

But cult leaders rarely last long at the top.

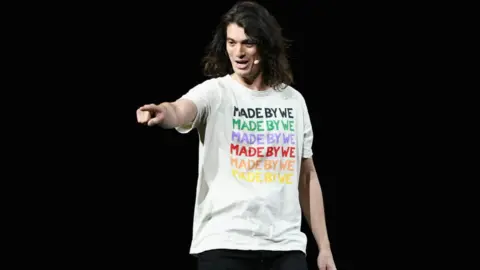

Former WeWork boss Adam Neumann:

Getty Images

Getty ImagesKnown to prefer T-shirts to suits, Mr Neumann's casual style was reflected in his approach to corporate governance.

Although his audacious way of doing business once attracted investors such as Softbank, the public market investors raised concerns about the firm's financing and oversight.

He co-founded WeWork in 2010 with a single office in New York's Soho.

Less than a decade later, it now has more than 500 locations in 29 countries. But it lost about $900m in the first six months of this year.

As the numbers have grown bigger, so has the scrutiny from investors who have questioned the links between Mr Neumann's personal finances and WeWork.

They also worried about his judgement, amid complaints about his hard-partying ways.

But Mr Neumann's fate sealed after plans for a public share offering were shelved last month.

Shortly afterwards, Mr Neumann announced he would take a step back from the firm, saying scrutiny of his leadership had "become a significant distraction".

Former Uber boss Travis Kalanick:

Getty Images

Getty ImagesDuring his time at Uber, Travis Kalanick presided over a rampant culture of sexism, the covering up of a major hack, spying on journalists and, allegedly, the theft of trade secrets from Google.

Mr Kalanick became known for his aggressive business tactics. When New York Mayor Bill De Blasio threatened to limit the number of rideshare drivers allowed to work in the city, Uber added "De Blasio's Uber" feature, which showed no available cars or long waits for a ride.

When the city of Austin introduced a bill that Uber didn't like, the firm switched off services in the city.

In a widely reported email to staff ahead of a company party in Miami in 2013, Mr Kalanick - known as TK - asked employees not to have sex with each other if they were in the "same chain of command" or to throw beer kegs off tall buildings, and levied a $200 (£158) "puke charge" for anyone who was sick, presumably as a result of over-indulgence.

Eventually, in 2017, following a spate of apologies from Mr Kalanick for both his own behaviour and that of members of his leadership team, he resigned.

Like Mr Neumann, he also sold down his stake in the firm he founded to Softbank.

Ms Fongang describes people like Mr Kalanick as "honest and direct".

"They say what they think," she says.

But she says things go wrong when their actions don't match their words.

Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes:

Getty Images

Getty ImagesElizabeth Holmes also dropped out of college to work on the business venture that made her a billionaire.

The difference between her and Mr Neumann or Mr Kalanick is that the implosion of Ms Holmes' business, Theranos, has left her facing prison time.

She founded the firm on an idea for a drug-delivery patch that could adjust dosage to suit an individual patient's blood type and then update doctors wirelessly.

The patch never made it to market, but the big idea - the one upon which the whole hoopla of Theranos was built - was a machine that could test for a variety of diseases through only a few drops of blood from a person's finger.

There was just one problem: it didn't work.

A story in the Wall Street Journal in 2015, accusing the firm of not using its own machines to test blood samples, prompted an investigation by the US financial regulator, the Securities and Exchange Commission.

Within a year, Theranos had its licences revoked and began shutting down its labs.

Forbes magazine revised Ms Holmes' wealth down from $4.5bn to "nothing".

When should they go?

Ms Fongang says a boss should quit or be booted out when staff and investors lose faith in their ability to deliver on their vision.

"Not all start-up entrepreneurs are meant to be leaders," she says.

Some are great visionaries, while others are great inventors, she says. "They should stick to that."