IMF: What is it and why does it matter?

Getty Images/AFP

Getty Images/AFPThe UK faces another five years of high interest rates to stem rising prices, according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

What is the IMF?

The IMF is an international organisation with 190 member countries. They work together to try to stabilise the global economy.

Any country can apply to join, as long as it meets a few requirements. These include providing information about its economy and paying in a sum of money called a quota subscription. The richer the country, the larger its contribution.

The IMF does three main things to monitor and support the economy:

- Tracking economic and financial events. It monitors how countries are performing and potential risks, like trade disputes or the uncertainty caused by Brexit

- Advising its members on how to improve their economies

- Issuing short-term loans and assistance to countries who are struggling

These loans are mainly funded by quota subscriptions. In 2018, Argentina received the largest loan in the IMF's history at $57bn (£53.4bn).

The IMF can lend its members a total amount of $1tn.

What are the IMF's main achievements?

The IMF is often described as a "lender of last resort". In times of crisis, countries look to it for financial assistance.

Harvard University economist Benjamin Friedman argues it is difficult to measure its effectiveness because it is impossible to know whether its interventions have made things better or "worse than whatever the alternative would have been".

However, some praised the Fund's role in supporting Mexico after it declared it would be unable to repay its debts in the early 1980s.

In 2002, Brazil obtained IMF loans to avoid defaulting on its debts. The government was subsequently able to turn the economy around relatively quickly, and paid off its entire debt two years ahead of schedule.

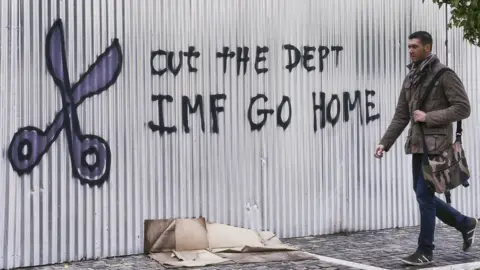

What are the criticisms of the IMF?

The conditions which the IMF imposes on the countries it lends money to have sometimes been criticised for being too harsh.

These have included forcing countries to reduce government borrowing, cut corporate taxes and open up their economies to foreign investment.

Greece was where the eurozone financial crisis started back in 2009, and the hardest-hit economy.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAfter it received bailout loans from the IMF, Greece had to make significant changes to its economy.

Critics said the austerity policy which the IMF insisted Greece followed - intended to get government borrowing down - was excessive and damaged its economy and society.

Who heads the IMF?

Kristalina Georgieva has been the IMF's managing director since 2019.

The economist was previously chief executive of the World Bank, and took over from Christine Lagarde, who is now the president of the European Central Bank.

AFP

AFPMs Georgieva is the first person from Bulgaria - one of the poorest members of the European Union (EU) - to lead the IMF.

Since the organisation was created, a European has traditionally been in charge, with a US national taking on the presidency of the World Bank.

Ahead of her first annual conference in 2019, Ms Georgieva warned that Brexit would be "painful" for the UK and the EU.

Why was the IMF created?

The IMF was created out of the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944 in the US.

It was attended by delegates from 44 countries during World War Two, including the United Kingdom, the US and the then Soviet Union.

They discussed post-war financial arrangements, including how to set up a stable system of exchange rates and how to pay for rebuilding damaged European economies.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesTwo organisations were later set up to meet these aims: the IMF and the World Bank.

Members of the newly-founded IMF agreed to a system of fixed exchange rates, which would stay in place until the early 1970s.

What is the UK's history with the IMF?

The UK was one of the IMF's original members, joining in 1945.

In 1976, under Labour PM James Callaghan, the UK was forced to seek a $3.9bn (£3.6bn) bailout loan from the organisation.

It followed soaring inflation in the early 1970s which saw the pound tumble in value against the US dollar.

At the time, it was the largest amount ever requested from the IMF.

In return, the UK was required to cut spending and balance its budget, which helped investors regain confidence. By March 1980, the pound had recovered.

In September 2022, the IMF was extremely critical of the unfunded tax-cutting plans announced in the Conservative government's mini-budget. The proposals were subsequently abandoned.

In October 2023, the IMF said it expects inflation to be higher in the UK than in any other G7 country in 2023 and 2024, and that UK interest rates will remain relatively high until 2028.