‘No-one asks new dads how they’re feeling at work’

Dave Edwards

Dave EdwardsDave Edwards says his son was born screaming and didn't stop for 12 months.

It was a tough introduction to parenting for the 33-year-old who spent those early days at home on paternity leave. Severely sleep deprived, he returned to his job in human resources five weeks after the birth.

"I was in a fairly frequent state of worry, worry about my partner at home with a screaming baby. I had a job to do that was quite stressful," the Brisbane, Australia-based father says.

A few months later he felt the full grip of anxiety and depression take hold.

Mr Edwards later discovered he was one of the numerous men who suffer from mental illness that arises after the birth of a child.

Advocacy group Postpartum Support International says in the US, one in seven mothers, and one in 10 fathers, will experience postpartum (after birth) depression. The group says those rates are broadly reflected across the developed world.

In the UK, research by parenting group the NCT found that more than a third of new dads were worried about their mental health, citing factors including added financial responsibility and lack of sleep.

For Mr Edwards, his struggle was made more difficult by responsibilities at work.

He remembers staring at the computer screen, feeling constantly agitated and struggling to concentrate.

"I was expected to just get back on the horse and fulfil my pre-dad life at work," the father of two says.

It's a story familiar to many women. Mothers remain the dominant caregivers and have long wrestled with how to balance careers and family.

But many fathers are showing signs of strain in the workplace as obligations outside their jobs grow.

'Anxiety is rising'

Amy Beacom, founder of the Centre for Parental Leave Leadership, works with companies like Microsoft and energy firm Phillips 66 to provide coaching and training tied to parental leave.

She says the pressures commonly felt by mothers are increasingly weighing on fathers who no longer just need to "bring home the pay cheque".

"Now they are expected to be at home too and their stress levels are rising, their postpartum depression levels are rising, and their anxiety is rising. That has very real effects in the workplace," Ms Beacom says.

Her US-based organisation wants companies to conduct mental health screening during the perinatal period, which runs from pregnancy to one year after birth, for mothers and fathers.

"We're doing it for the mums and we're pushing it for the dads," she says.

Shifting landscape

Those kinds of screenings may be some way off but companies are taking other steps to support dads at work.

"Men are more involved in their kids' lives more than ever before. But what hasn't changed is the number of hours that men are working," says Kiri Stejko, chief services officer at Parents at Work.

The consultancy provides workplace training to clients in Australia, the UK and Hong Kong to help parents juggle career, family and wellbeing.

She works with firms including Deloitte and HSBC, and says employers want to make the issue not just about women and babies, but about families and parents.

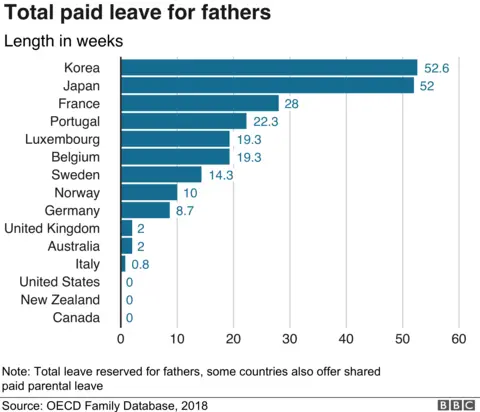

At a practical level, that means extending programmes previously targeted towards women, like leave to care for a new baby or flexible work arrangements.

Many men want to work more flexibly, Ms Stejko says, but find it is "not really accepted yet".

Some men feel there's a stigma tied to pulling back from work and asking for help can seem too risky to their career.

It's a concern observed by father of five Alex Laguna, who set up the website BetterDads. Initially a platform to support men going through divorce, the site now also touches on wider issues of work and family.

Mr Laguna says men often struggle to step away from their jobs, hung up on worries over how it will look to "other men we work with".

"It's really very nerve-wracking to say no to work," the Sydney dad says.

Johan Bävman

Johan BävmanThe 44-year-old, who also runs a lighting company, says his generation hasn't had many role models on how to balance family and work in the way that is now expected.

"We're the first to go through it, we're faced with a lot of challenges."

Starting conversations

Experts welcome efforts by companies to support working dads while calling for more to be done to build awareness.

Terri Smith, chief executive of not-for-profit group Perinatal Anxiety and Depression Australia, says many people aren't aware that perinatal mental illness affects men - and therefore can't offer support.

She says the first step is recognising it is "a real illness" and starting discussions about it in the workplace.

Mark Williams from Bridgend in Wales suffered from depression after the traumatic birth of his son, and found returning to work as a sales and marketing trainer so difficult that he had to resign. He founded the charity Fathers Reaching Out and campaigns to raise awareness in the UK.

"It is not just depression, men could be suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, or anxiety," he says. "You may already be mentally suffering at home, and all of a sudden, bang, two weeks after the birth, it is time to go back to work."

He says managers and health professionals need to ask new fathers how they are feeling and be prepared to provide support.

Mr Edwards agrees, and thinks he would have benefited from his boss simply checking in on him after he returned to work.

"I would get a lot of how's everything going at home, how's your partner going? But nothing about me," he says.

Johan Bävman

Johan BävmanThe public sector worker says he's in a much better place now and wants to help others.

"Showing the new dad that looking after themselves is really important, because how I felt through those dark few months… it wasn't pleasant and I know it had an impact on my work as well."