Should we dislike the 'Like' button?

BBC

BBCLeah Pearlman draws comics about ideas like "emotional literacy" and "self-love". When she began posting them on Facebook, her friends responded warmly.

But then Facebook changed its algorithm - how it decides what to put in front of us. When social media is a big part of your life, an algorithm change can come as a shock.

Leah's content was being shown to fewer people, and her comics started to get fewer likes.

"It felt like I wasn't getting enough oxygen," she told Vice.com. "It was like, 'Wait a minute, I poured my heart and soul into this drawing, but it's only had 20 likes.'"

It's easy to empathise. Social approval can be addictive, and what's a Facebook "like" if not social approval distilled into its purest form?

Researchers liken our smartphones to slot machines, triggering the same reward pathways in our brain.

Prof Natasha Dow Schull argues that slot machines are addictive "by design", and that casinos aim to maximise "time on device". They want to keep people in front of their screens, admiring the pretty lights and receiving those dopamine hits.

Social media firms have taken note. More likes, new notifications, even an old-fashioned email - we never know what we'll get when we pick up our phone and pull the lever.

Faced with a sudden drop in likes, Leah is embarrassed to say she began buying ads on Facebook "just to get that attention back".

There's an irony behind her discomfort.

Before she was a comic artist, Leah was a Facebook developer, and in July 2007, her team invented the "like button".

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

The concept is now ubiquitous across the web, from Facebook to YouTube to Twitter.

The benefit for platforms is obvious. A single click is the simplest way for users to engage - much easier than typing out a comment.

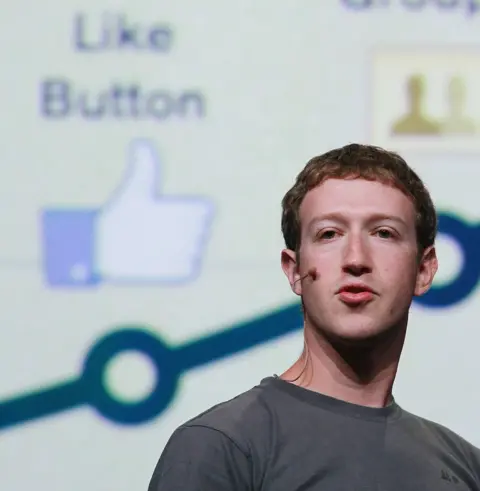

But the idea took a while to refine. As Leah Pearlman remembers, Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg took some convincing.

Should it be called the "awesome" button? Did the symbol work?

While a thumbs-up means approval in most cultures, in others it has a much cruder meaning.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEventually, in February 2009, the Like button was launched. "The stats went up so fast. Fifty comments became 150 likes, almost immediately, Leah Pearlman recalls.

"People would start making more status updates, so there was way more content, and it all just worked."

Meanwhile, at Cambridge University, Michal Kosinski was doing a PhD in psychometrics - the study of measuring psychological profiles.

Another young research, David Stillwell had written a Facebook app to test the "big five" personality traits: openness, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness and neuroticism.

Taking the test gave the researchers permission to access your Facebook profile, with your age, gender, sexual orientation and so on. The test went viral.

The dataset swelled to millions of people, and the researchers could see everything they had ever "liked", as well as the public data of their friends.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesKosinski - now a professor of organisational behaviour at Stanford University - realised this was a treasure trove of potential insights.

For example, it turned out that a slightly higher proportion of gay men than straight men "liked" the cosmetics brand MAC. That's only one data point, since Kosinski couldn't tell if someone was gay from a single like.

But the more likes he saw, the more accurate guesses he could make - about sexual orientation, religious affiliation, political leanings, and more.

Kosinski concluded that if you'd liked 70 things, he'd know you better than your friends. After 300 likes, he'd know you better than your partner.

Facebook has since restricted which data gets shared with app developers.

But one organisation still gets to see all your likes and more besides: Facebook itself.

And it can afford to employ the world's brightest machine-learning developers to tease out conclusions.

Facebook

FacebookWhat can Facebook do with its window into your soul? Two things.

First, it can tailor your newsfeed so you spend more time on Facebook - whether that means showing you cat videos, inspirational memes, things that will outrage you about Donald Trump, or things that will outrage you about Donald Trump's opponents.

This isn't ideal - it makes it harder and harder for people with different opinions to conduct a sensible conversation.

Second, it can help advertisers to target you. The better the ads perform, the more money it makes.

Targeting adverts is nothing new.

Long before the internet and social media, if you were opening a new bicycle shop in Springfield, say, you might have chosen to advertise in the Springfield Gazette or Cycling Weekly, rather than the New York Times or Good Housekeeping.

Of course, that still wasn't very efficient. Most Gazette readers wouldn't be cyclists, and most subscribers to Cycling Weekly wouldn't live near Springfield. But it was the best you could do.

You could say that Facebook simply improves that process.

Who could object if you ask it to only show your ads to Springfield residents who like cycling? That's the kind of example which Facebook tends to cite when it defends the concept of "relevant" advertising.

But there are other possible uses which we might not like.

More things that made the modern economy

How about offering a house for rent, but not showing that advert to African Americans? Julia Angwin, Madeleine Varner and Ariana Tobin from the investigative website ProPublica wondered if that would work, and it did.

Facebook said oops, that shouldn't have happened, blaming a "technical failure".

Or how about helping advertisers reach people who have expressed interest in the topic of "Jew hater"? The same ProPublica team showed that was possible, too. Facebook said oops, it wouldn't happen again.

This might worry us because not all advertisers are as benign as bicycle shops - you can also pay to spread political messages, which may be hard for users to contextualise or verify.

The firm Cambridge Analytica claimed it had swung the 2016 election for Donald Trump, in part by harnessing the power of the Like button to target individual voters - much to the horror of Michal Kosinski, the researcher who had first suggested what might be possible.

What about helping unscrupulous marketers to pitch their products to emotionally vulnerable teenagers at moments when they're feeling particularly down?

In 2017, the Australian reported on a leaked Facebook document apparently touting just this ability.

Facebook said oops, there'd been another "oversight", insisting it "does not offer tools to target people based on their emotional state".

Let's hope not, especially as Facebook has previously admitted to manipulating people's emotional states by choosing whether to show them sad or happy news.

In a widely-quoted Facebook post from December 2018, chief operating officer Sheryl Sandberg apologised for mistakes made by the company. "Prior to 2016, we were not as focused on preventing harm as we should have been," she says. "And we did not do enough to anticipate other ways our platform could be misused."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesShe acknowledges that many people have lost trust that Facebook would "respect and protect the personal information of our users" or "always operate with integrity", and insists the company is listening and learning.

But in reality, it seems Facebook's potential for mind control is far from perfect.

Some experts who've looked into Cambridge Analytica question how effective it really was. And for all the targeting, analysts report that the click-through rate on Facebook adverts still averages less than 1%..

Perhaps we should worry more about Facebook's undoubted proficiency at serving us more adverts by sucking in an inordinate amount of our attention, hooking us to our screens.

How should we manage our compulsions in this brave new social media world?

We might cultivate emotional literacy about how the algorithm affects us, and if social approval feels as vital as oxygen, maybe more self-love is the answer.

If I see any good comics on the subject, I'll be sure to click "like".

Correction: This article was amended on 25 June to say that the Facebook personality app was written by David Stillwell.

The author writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen to all the episodes online or subscribe to the programme podcast.