Gold: Gordon Brown's sale remains controversial 20 years on

Reuters

ReutersIt was called one of the worst investment decisions of all time.

Twenty years ago on Tuesday, then Chancellor of the Exchequer Gordon Brown said he was selling tonnes of Britain's gold reserves. Trouble was, his timing could barely have been worse.

"It was the bottom of gold's two-decade bear market," says Adrian Ash, director of research at investment firm BullionVault.

Hindsight may be a wonderful thing, but Mr Ash points out there were plenty of people warning against the move at the time - including at the Bank of England.

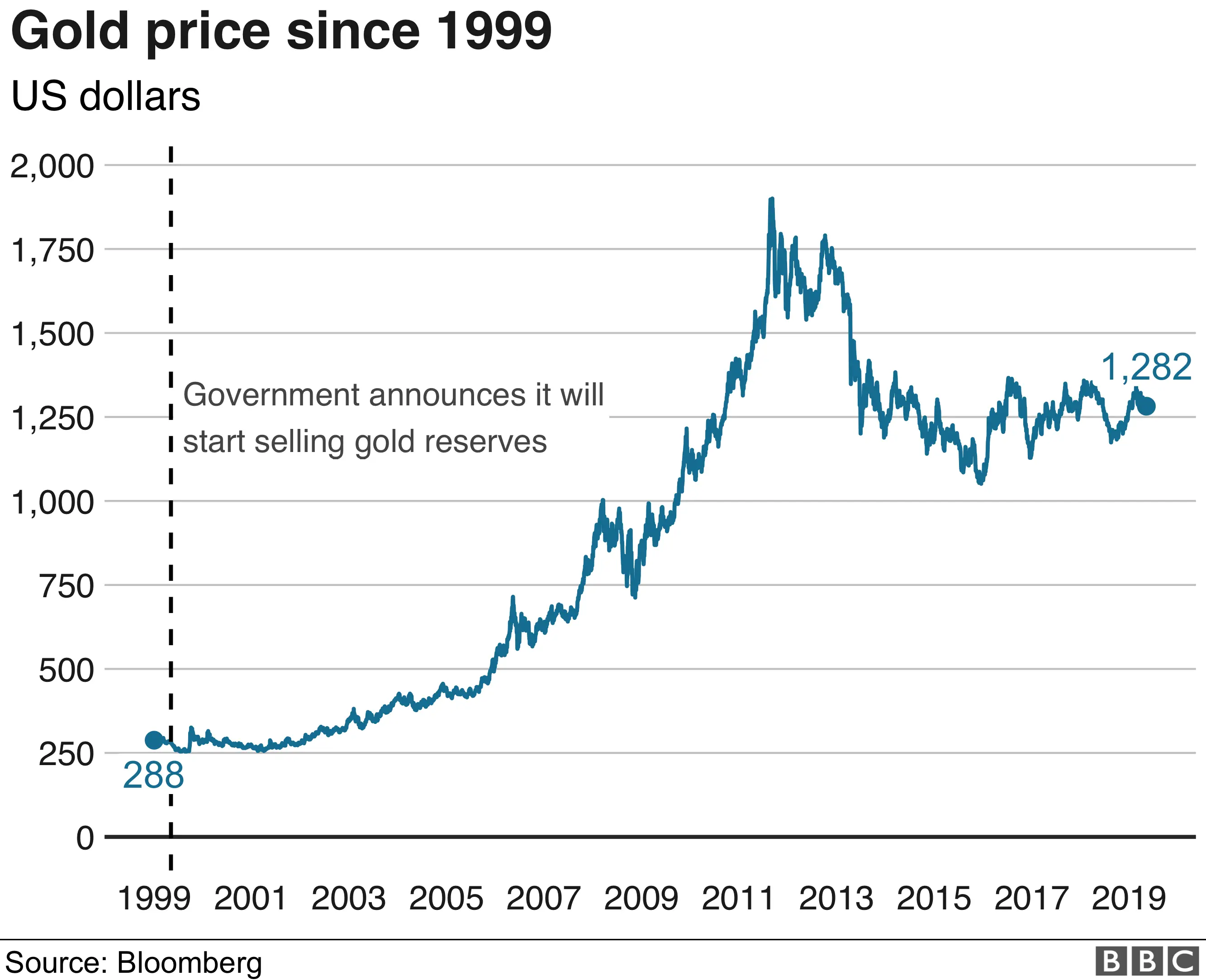

Between 1999 and 2002 the Treasury sold 401 tonnes of gold - out of its 715-tonne holding - at an average price of $275 an ounce, generating about $3.5bn during the period.

Mr Ash says the average price since the sales ended has been almost $1,000. In 2011 the price reached more than $1,900 an ounce, and on Monday stood at about $1,279.

'The final blow'

Despite these headline numbers, at the time it seemed perfectly sensible to many at the Treasury.

Other central banks were also selling gold. According to BullionVault, Belgium, Canada and the Netherlands had already sold 1,590 tonnes between them since 1990. In 1997 alone, Argentina and Australia sold a combined 290 tonnes.

And in April 1999, Switzerland voted in a referendum to sever the Franc's gold backing, effectively approving a plan to sell 1,300 tonnes from its 2,590-tonne hoard.

Writing in his 2007 book The Ages of Gold, Timothy Green says: "The erosion of the gold price during the late 1990s owed much to steady, but uncoordinated, central bank selling."

But he adds: "The final blow, [the UK's sale] sent a terrible signal to the market."

PA

PALondon had been the centre of the gold market for 300 years. The circumstances of the UK sale fuelled a belief that a modern economy no longer needed to hold huge gold reserves (an argument that still persists today).

News of the sale emerged during a planted question in the House of Commons on a Friday afternoon in May 1999.

That prompted a 10% fall in the metal's price. Revelations that the sale would be staggered via auctions telegraphed to the market that the price was likely to remain depressed.

It all gave the impression that for governments, holding bullion as a store of value and useful hedge against inflation was becoming irrelevant, says Mr Ash: "Central banks thought they could manage the world by tweaking interest rates, switching a few dials. Gold's role as a financial backstop had diminished."

The new backstop

This view that gold no longer glistened was underlined in a New York Times' editorial in May 1999, headlined: Who Needs Gold When We Have Greenspan. "Dollarization... amounts to a sort of a gold standard without gold," it said.

In other words, Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan and the US dollar were the new backstop. (The article did caution, though, that this could all change "if it turns out that central bankers are not the geniuses they are now deemed to be").

There was an end-of-millennium feel that gold was history, says Mr Ash.

Globalisation was re-ordering the financial world; the euro created a new - and, hoped-for, stronger - monetary system; there were calls for the International Monetary Fund to sell its gold to help write off Third World debt; private investors had lost interest in the precious metal, preferring to help fuel the dotcom bubble.

In this context Mr Brown's decision does not necessarily look out of step.

The money raised from the gold sale was put into assets that yielded a return - bonds and currencies. The sale of what was then regarded as a legacy asset would make money, not lose it, according to the Treasury.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEven so, says Mr Ash, other nations baulked at the "ham-fisted" way in which the UK chancellor went about the sale. He cites the Central Bank Gold Agreement, signed in September 1999 and designed to prevent the markets being spooked by another sudden sell-off.

The agreement involved 15 central banks promising to cap sales over the following five years, a move designed to provide clarity to the financial markets and put a floor under the gold price. "It was," says Mr Ash, "a slap on the wrist for the UK."

Has there been any lasting impact? Rhona O'Connell, head of market analysis for Europe and Asia at global financial services firm Intl FCStone, says no.

She recalls the shock among the influential bullion banks when the decision was announced, but this subsided once it was accepted that it was the Treasury's decision, not the Bank of England's.

International credibility

"It was irritating at the time that the Bank of England carried the can [initially] for a decision made by the then chancellor," she said.

The debate continues on the need for governments to hold large reserves of gold. Critics argue that storing a precautionary asset whose value would probably fall as you sold it is somewhat purposeless. It remains anachronistic, they say.

But for Ms O'Connell: "Regardless of its price on any date, gold is negatively correlated with virtually all other asset classes and from a central banker's point of view it is important in terms of adding international credibility within the financial sector."

Some countries - she cites Vietnam as a good example - have bought gold as security for raising money on the international financial markets in order to avoid default.

It's clear that for many governments, the demise of gold has been greatly exaggerated. The World Gold Council (WGC) says that purchases by central banks in the first three months of 2019 were the highest in six years as countries diversified away from the dollar. China and Russia were the biggest buyers.

Central banks bought 145.5 tonnes of gold over the January-March period, 68% more than a year earlier. It followed purchases of 651.5 tonnes in 2018, the most since 1967.

"Given the strategic nature of central bank buying, we expect the momentum to continue," the WGC's head of market intelligence Alistair Hewitt said, adding that he expected central banks to buy 500-600 tonnes this year.

Gordon Brown may have had many legitimate reasons for selling Britain's gold, but claims it was because bullion was yesterday's asset probably isn't one of them.