Is WeWork really worth nearly $50bn?

WeWork

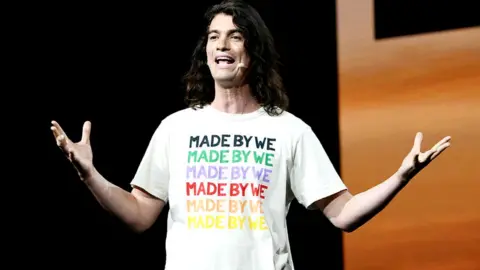

WeWorkThe We Company is a business that defies description, at least according to its co-founder and chief executive Adam Neumann.

But for many it's the firm's valuation that is really defying explanation.

As it prepares for a stockmarket listing, the parent company of WeWork, provider of trendy shared office space, looks set to be valued at around $47bn (£36bn).

That puts it in the same bracket as the slate of high-profile technology companies that are also floating their businesses, and have attracted sky-high valuations based on the idea they will reap big rewards from disrupting established markets.

Like them WeWork boasts a "millennial-friendly" outlook and aesthetic. The bright, airy and comfortable offices it rents out are built around community so people can choose to work in an office or in a shared space, where they can log-on to wifi, hold meetings and get to know others also using the facilities. A nearby kitchen complete with beer on tap is likely a draw as well.

Underneath the beautiful decor though, some argue We Company is really just a real estate company, prompting the question: should it have such a high market value?

What is the We Company?

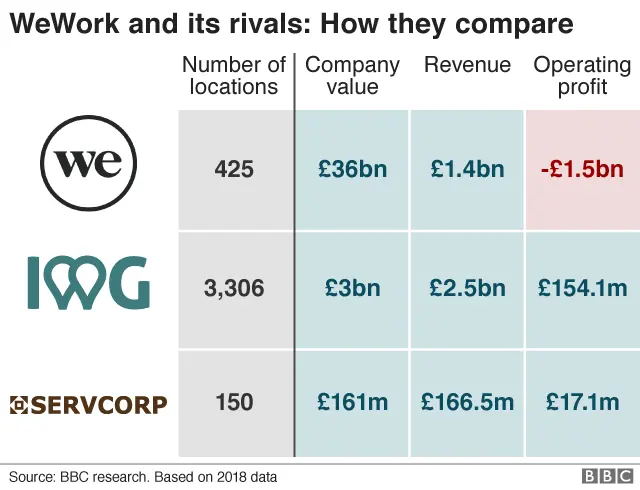

WeWork was established in 2010, just as the financial crisis took the bottom out of the office rental market. WeWork now has 425 locations in 100 cities and boasts 401,000 members - those who use the offices.

The We Company has also branched out into residential spaces with WeLive where people can rent fully furnished apartments for a few nights or a number of months.

WeGrow, its school for 2-11 year olds, says it is committed to "unleashing every human's superpowers".

Mr Neumann told Forbes magazine the firm's valuation has more to do with its size, its "energy and spirituality" than its revenues. While revenues are growing, it hasn't met its most recent targets and it is loss-making.

While WeWork, WeLive and WeGrow may have the look and feel of a disruptive tech company with their light, airy designs, colourful squishy sofas and beer taps, analysts like Calum Battersby, at Berenberg argue it is not so very different from rivals IWG, which used to be known as Regus, and Australia's ServCorp which also offer serviced office space.

"It is a real estate company, undoubtedly," he says and as such is quite a capital intensive business to run.

Tech firms like Uber, the ride sharing and food delivery app, are platform-based businesses, requiring upfront investment. But We needs more capital to keep operating.

"Every bit of revenue they earn, they are going to have to invest a lot in getting a lease on the office, doing up the office, segmenting it into smaller sites that you can sell to people and companies just like any traditional office company," says Mr Battersby.

Expanding into new areas also requires a lot of money; last year it burned through $2.3bn in cash.

Who has invested in We?

The We Company has attracted a roster of high profile investors including Goldman Sachs and JPMorgan to fund its expansion.

But it was when Softbank, the Japanese technology conglomerate, got involved with the We Company that the value of the business really shot up.

Softbank and We initially struck a $4.4bn deal in 2017 which gave the firm a valuation of $20bn.

Rett Wallace, founder and chief executive of Triton Research, says the firm's track record on fundraising has been "astonishing".

"If you just look at the nuts and bolts of what they do, it doesn't explain how they have been able to raise so much money," he says. "And the people they have raised the money from are not idiots."

Recently though, the flow of money from Softbank has been pared back. In January, the Japanese firm invested $2bn in the company in January, well below the $16bn WeWork was reported to have been seeking.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMeanwhile, the firm hasn't hit projected financial targets. Instead of expected revenue of $2.8bn last year sales were $1.8bn.

It had hoped for a profit of $941.6m. It made a loss $1.9bn.

We has surpassed its target for 260,000 WeWork members. But it wanted 34,000 WeLive members and the residential business was supposed to make up a third of total revenue, neither of which has happened.

So far, the furnished apartment business WeLive only has two sites, in New York and Washington DC, though it is planning to open in Seattle in 2020.

But Artie Minson, We's president and chief financial officer, is upbeat, recently telling investors it ended 2018 with $6.6bn in cash and is still "in the early stages of disrupting real estate, the largest asset class in the world."

Is the We Company a 'disruptor'?

While Charles Clinton, co-founder and chief executive of online real estate investing and finance platform EquityMultiple agrees that We is essentially a real estate company, he says its approach has shaken up the serviced office sector.

"I think that they have expanded the base that accesses these kind of services very dramatically by marketing to a new audience, much like Apple has been able to do. Sometimes style alone is a form of disruption."

The shared residential market is also ripe for disruption, according to Mr Clinton, making WeLive the most promising business under the We umbrella.

Although other things the company has done "feel a little bit more scattershot by comparison" he adds.

Take Wavegarden, a Spanish firm that generates ideal conditions for surfers - a hobby Mr Neumann reportedly enjoys.

The We Company paid $13.8m for a 42% stake in Wavegarden. It wrote down the value of its holding to zero a year later though a We spokeswoman says Wavegarden is now "seeing strong demand".

Wavegarden

Wavegarden Whether We will be able to continue making leftfield deals such as this once they have public investors to answer to isn't clear.

Also likely to raise questions is a practice where Mr Naumann leases buildings which he part owns to WeWork. The Wall Street Journal reported that the firm paid more than $12m in rent to buildings "partially owned by officers" of WeWork between 2016 and 2017.

A spokeswoman said these deals have been disclosed to its board and investors, adding: "We have a policy in place that provides review and approval procedures for related party transactions."

Mr Clinton says that deals such as these can work "if your private market investors are okay with it".

However, he says: "In a public company where you have to be much more responsive to both your investors and the Securities and Exchange Commission, that becomes a lot more tricky."