What the Airbnb surge means for UK cities

Rooms available to book on Airbnb have rocketed in number in major UK cities, leading to fears of "hollowed out communities" as tourists flock in.

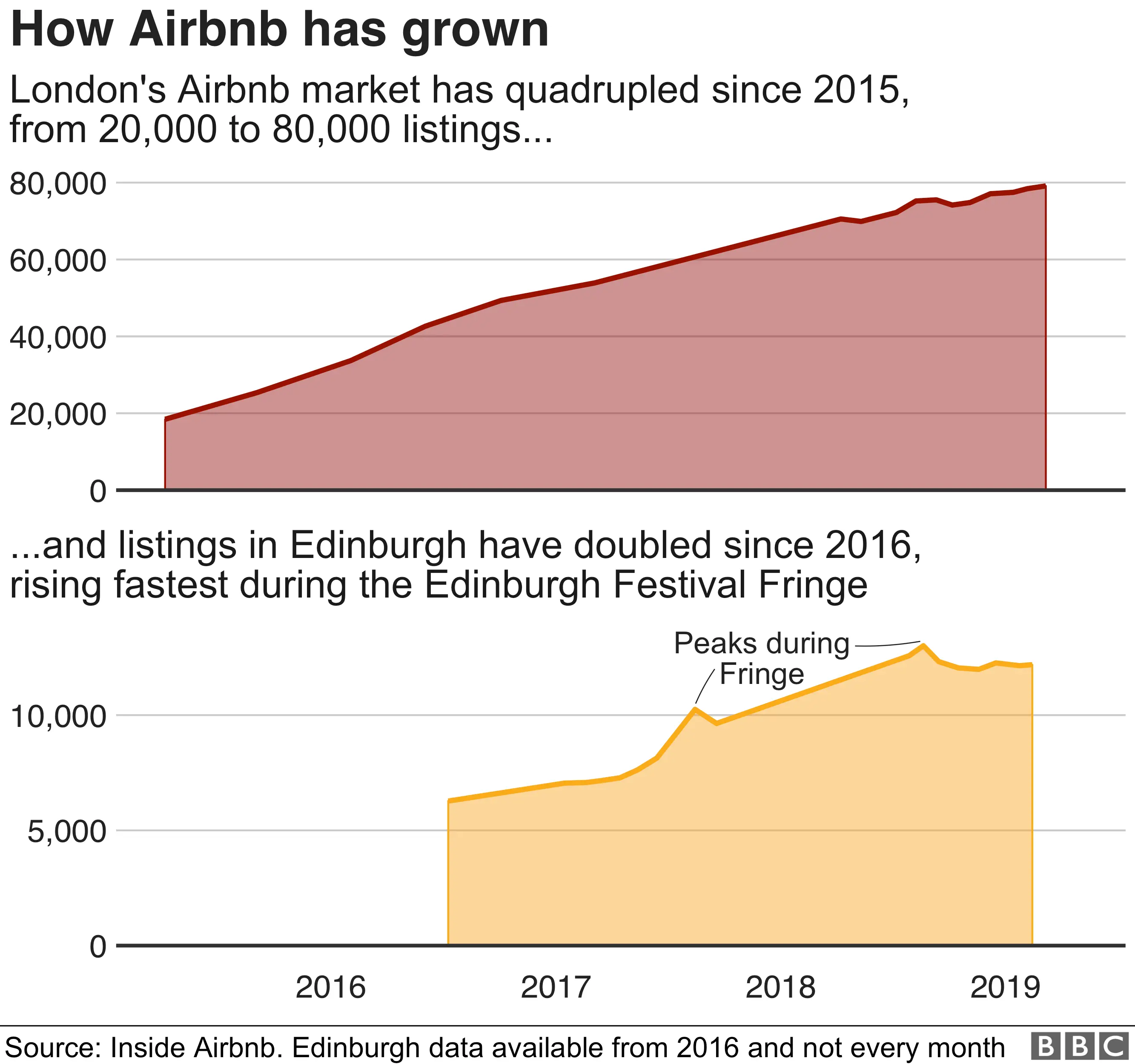

Data analysed by the BBC suggests that listings in Edinburgh doubled in three years, and shows a fourfold increase in spaces in London since 2015.

City of Edinburgh Council has called for licensing and London councils want a registration scheme for hosts.

Airbnb said it led the way on "clear and proportionate" rules.

"Airbnb is the only platform that voluntarily works with UK cities to help hosts share their homes, follow the rules and pay tax. Other platforms and providers need to step up and follow our lead," the company said.

"[The platform] allows local families and businesses to benefit from visitors to their communities."

How many properties are listed?

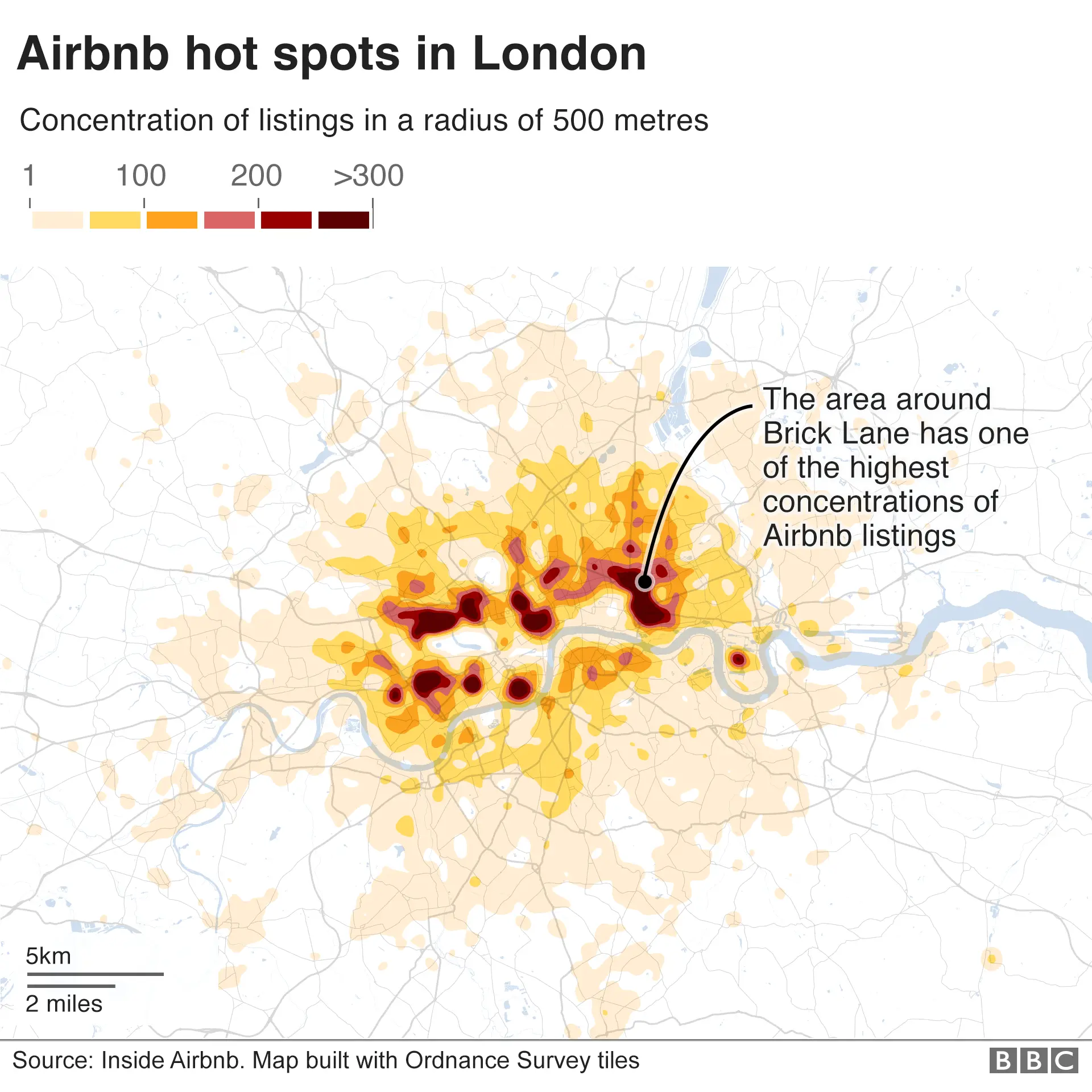

Nearly 80,000 rooms or homes in London are listed on Airbnb - more than any other UK city, according to figures from housing advocacy site Inside Airbnb analysed by the BBC.

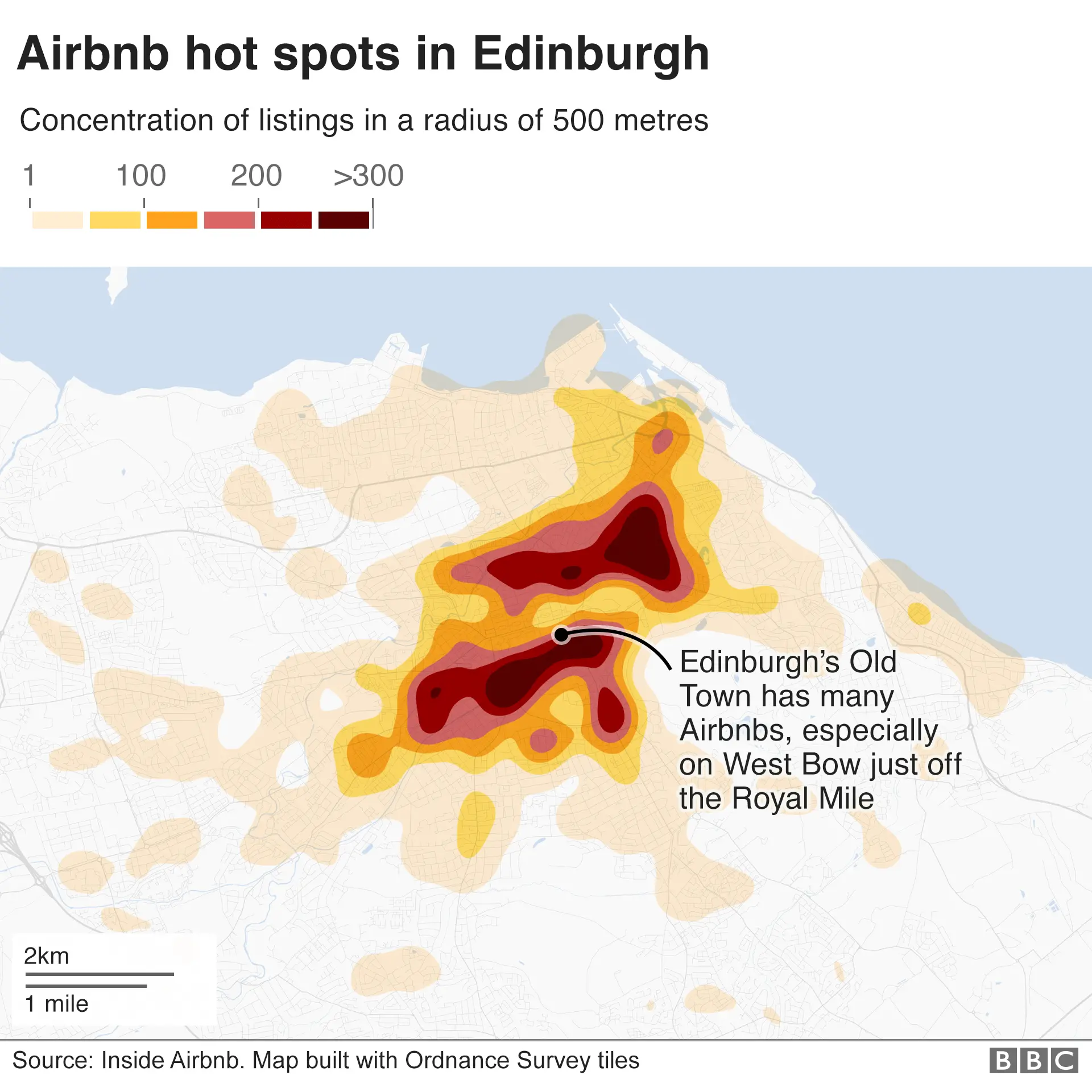

Just over 12,000 are listed in Edinburgh, but the effect is greater than in London as this accounts for a much bigger proportion of the city's property and population.

Edinburgh's 12,000 listings work out to around one Airbnb listing for every 42 residents, while London's Airbnb market equates to one listing per 112 residents.

Much of this accommodation is centred around Edinburgh's Old Town - a huge draw for tourists especially during the annual Fringe festival. Airbnb said its activities had boosted the Scottish economy by £1.5m a day, and the UK economy as a whole by £3.5bn last year.

One result has been concern among locals and politicians of a squeeze on housing for residents, the behaviour of some visitors in residential blocks, and differing tax treatment for traditional hotels and guesthouses.

Examples of anti-social behaviour in "party flats" have been highlighted by campaigners for greater regulation.

They included loud, late-night noise affecting one young woman's exam preparation, and an amorous couple bursting into the home of a resident aged in her 80s before realising they had the wrong flat.

Councils say it is expensive and time-consuming to tackle such problems with their existing powers. They can only do so after complaints, rather than proactively.

"Short term lets are having a terrible impact. They are hollowing out communities, both in the city centre and increasingly across Edinburgh. Residents are putting up with high levels of anti-social behaviour and, very worryingly for us, we believe there is a huge impact on housing supply," said Councillor Kate Campbell (SNP), housing convenor at City of Edinburgh Council.

"Housing in Edinburgh is under enormous pressure and we need to take every action we can to protect supply and keep homes affordable for residents, as well as protecting communities."

The Scottish government has been asked to consider a licensing scheme - allowing for checks, safety requirements, and the potential for a cap on numbers. Housing Minister Kevin Stewart (SNP) said it was considering what measures could be required, which would be put to consultation "to ensure we get the balance of short-term lets right in Scotland". He said there would be a further announcement within a week.

Airbnb said it took action when alerted to rare cases of bad behaviour, pointed out that hosts are subject to income and council taxes, and said it welcomed regulation.

However, it also argued that its growth had little effect on the availability of homes for locals to buy or rent, highlighting various studies which had shown that house building had not kept up with demand, and had pushed up prices as a result.

It said entire home listings on Airbnb represented less than 0.6% of the available housing stock in Scotland, and some listings on its site were bed and breakfasts, or small hotels, rather than residential property.

'Trendy' Shoreditch on the map

One of the most popular areas for Airbnb listings in the country is Shoreditch, in London. Its reputation for a thriving nightlife and cultural scene means many listings in the area advertise their "trendy" location.

The result is the common sight of visitors "hanging around with Google Maps on their phones", trying to find their accommodation which could be good for trade, according to local trader Phil Blackman.

Mr Blackman sells shoes just off Brick Lane and says Airbnb has encouraged people to come to the area.

"It is good value for money for them, and they have got to stay somewhere," he said.

He argued that people working in finance in the City and living there for only a year or two, while offering little to the area, were more responsible for any loss of community spirit.

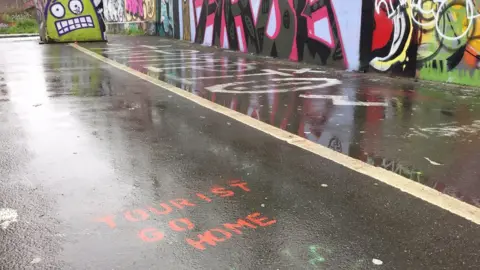

The debate is reflected in one piece of graffiti. "Tourist go home," it says, but underneath someone has added: "But we love this place".

Isn't this just a good use of spare rooms?

Many tourists applaud Airbnb for the opportunity to visit cities without paying large city hotel rates. Many homeowners join the chorus, saying the income from occasionally letting a spare room helps pay the bills.

However, concerns have been raised that landlords have shifted from offering long-term tenancies to these short-term lettings, restricting supply for people who want to live and work in these cities and putting up the cost of rent as a result.

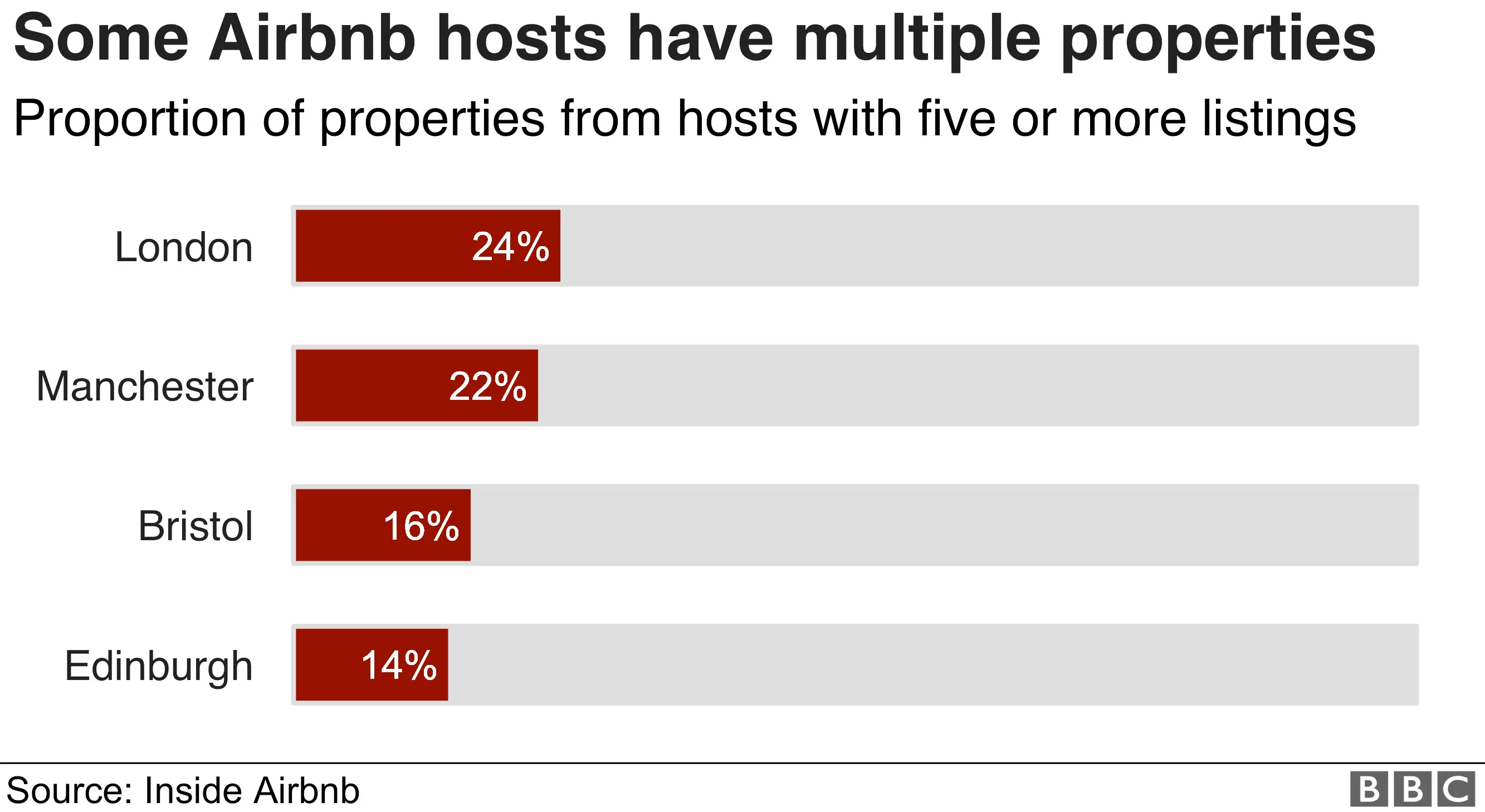

Nearly half of listings come from hosts with more than one property, and in London, 24% of listings are by hosts with five or more sites. It is a similar picture in Manchester and Bristol, according to the Inside Airbnb data.

One per cent of hosts control 17% of the London's Airbnb market.

In Bristol and Edinburgh, 1% of hosts are responsible for 11% of listings, and in Manchester it is 10%.

In London, there are 11 Airbnb hosts with more than 100 listings each.

Eight of the 11 are listed with human-sounding host names, like "Sally", offering 279 listings, "Veronica" (195), and "Emily" (179).

Airbnb argued that all three identified themselves, basically as property managers. It said hosts may manage the listing process on behalf of a number of different individuals.

Do limits work?

A 90-day a year short-term let limit for whole homes has been in operation in London since 2015. Owners wishing to let for longer may require planning permission for a "change of use" from their local council.

Only six changes from a home to a hotel have been approved since the limit was introduced, according to Freedom of Information requests the BBC sent to 32 London boroughs.

Airbnb is currently the only platform to have voluntarily implemented the 90-day limit automatically on its platform.

The Mayor of London, Labour's Sadiq Khan, wrote in March 2017 to six other online short-term letting platforms operating in London - Veeve, Onefinestay, Wimdu, Booking.com, HomeAway and Airsorted - urging them to follow Airbnb's lead.

Homeaway and TripAdvisor have committed to introducing a cap in the future, but other providers have not. This 90-day rule can be easy to flout, London councils told the BBC in 2017. The Mayor of London said on Tuesday that the law was "near-impossible for councils to enforce".

Mr Khan has now called on the government to introduce a new registration system for anyone wanting to rent out a property for less than 90 days a year - to make it clear who is operating in this sector.

Airbnb is supporting this idea. It said it had a team that worked to prevent, detect, and tackle attempts to avoid night limits, and suggested other providers had failed to follow suit.

Outside London, planning is more of a grey area. If the property is primarily a home, with a room to let, then planning permission is probably not needed. A planning authority can determine whether there has been a material change of use.

A certification scheme for all types of short-term accommodation is operating in Northern Ireland - the only part of the UK which has one.

Data source: Inside Airbnb, which provides snapshot views of Airbnb listings for four UK cities (London, Manchester, Bristol, Edinburgh), from various dates 2015-2018.