Meet the tech entrepreneurs tackling sexual harassment

Shai Dolev

Shai DolevWhen Neta Meidav was sexually harassed at work aged 22, she felt it was easier to quit her job than report it to human resources.

But more than a decade later, the #MeToo movement came along, kicked off by rape and sexual harassment accusations against movie mogul Harvey Weinstein.

It quickly galvanised people across the world to share their own stories.

So Ms Meidav has created a blockchain-powered app to help encourage individuals to speak up. Vault Platform, set to be piloted by a small number of companies in March, enables those experiencing misconduct in the workplace to record a private, time-stamped report that is stored as evidence in a "private vault" on users' phones.

A "digital receipt" of the report is stored on the blockchain, so it cannot be tampered with and is almost impossible to steal or delete.

Users can send the reports to their company, but Vault also flags up if someone else in the same organisation has reported a similar incident or individual, giving people the impetus to report collectively.

"When I was harassed, I was terrified to report it," recalls Ms Meidav, now 34.

"I felt very much alone. But after I left I found out that I wasn't the only one. What we've seen now [with #MeToo] is that once one person speaks up then a wave of others come forward."

Vault, she believes, offers "strength in numbers".

Sexual harassment continues to be all too common and is far from limited to Hollywood. Scandals have have engulfed businesses such as Google, Uber and Fox News.

According to a study by Everyday Sexism Project and the Trades Union Congress (TUC), 52% of women have experienced unwanted sexual behaviour at work. Furthermore, a survey for BBC Radio 5 live in 2017 found that 63% of women who said they had been sexually harassed didn't report it to anyone, while 79% of men who'd been sexually harassed kept it to themselves.

JULIA SHAW

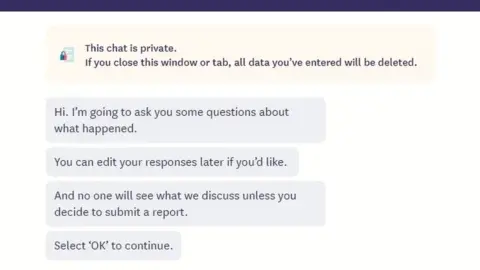

JULIA SHAWA start-up named Spot wants to change those figures.

Combining memory science and artificial intelligence (AI), the firm's app encourages those who have experienced workplace harassment to speak up.

"A lot of people don't report [harassment] because they're afraid of being judged by a human," explains Spot co-founder Dr Julia Shaw.

"And they're worried about all the meetings that might happen as a result."

Instead, people can talk to Spot, a platform where, according to Dr Shaw, "individuals can feel safe and anonymous and have control over the information they provide".

Dr Shaw, a memory scientist, believes that Spot garners stronger evidence than if the harassment had been reported to HR in the first instance.

"It effectively asks questions using cognitive interview best practices, which are used by the UK police to interview victims and witnesses," she says.

These techniques involve asking open-ended neutral questions to start with, then following up with specific questions.

Spot

Spot"It's never forcing or leading someone down a certain path," explains Dr Shaw. "It's a very practical approach and it's going to lead to better evidence."

Users can be sent a document of the interview or they can submit it to their employer when they're ready.

But Elisabeth Kelan, professor of leadership and organisation at the University of Essex, warns that such technology in the workplace can only go so far.

"While apps can make the recording process more efficient and accurate, it remains to be seen whether these technologies empower individuals to actually report sexual harassment," she says.

She believes senior leaders have a key role to play here.

"The most effective ways to challenge sexual harassment I have witnessed is if senior leaders call out this behaviour as inappropriate and sanction it. That sets an example that such behaviour is not tolerated."

Apps by themselves cannot create this culture, she argues.

Still, the power of an anonymous collective voice was demonstrated last year when a petition created through campaigning site Organise, complaining about the alleged harassment and "forced hugs" from Ray Kelvin, founder of British fashion company Ted Baker, attracted more than 2,500 signatures.

It forced Mr Kelvin to take a leave of absence.

Sunguk Moon

Sunguk MoonFounded in South Korea but now based in San Francisco, Blind is an anonymous social network for the workplace that allows employees from the same company to connect and talk secretly to each other.

Co-founder and chief executive Sunguk Moon was inspired to create Blind in 2013 after working at an internet company in Korea where employees could post anonymous messages on an internal forum.

"That's when I thought, 'What if there was a safe place to talk about work, the company cannot interfere with, and only accessible from your personal device?'

"It seemed clear to me that anonymity within the workplace increases the amount of communication, and this helps employees understand the workplace better."

In the wake of the Hollywood scandal, Blind launched a dedicated #MeToo section in February 2018 and saw a 50% increase in new users compared to the previous week.

"Some users posted stories about their experiences while others have posted questions asking for advice on taking action and reporting issues," says Mr Moon.

Judging by the rise of such apps around the world, sexual harassment is sadly widespread.

In the Philippines, for example, women's group Gabriela launched a Facebook chatbot called Gabby to help people report instances of sexual harassment.

And in Egypt for the last eight years, HarassMap has been providing a safe space in which witnesses or survivors of harassment can speak out, adding the location of the incident to the map.

"The map helps to demonstrate the prevalence of sexual harassment - not only visualising the number of reported incidents but also their spread across the country," says a HarassMap spokeswoman.

Ms Meidav says that such technology is essential to drive a change in culture.

"People can't go on harassing if there's technology that allows people to go after them and submit complaints together," she argues.

"It drives people to rethink their behaviour at work."