Could women solve the global pilot shortage?

Claire Banks is about to fulfil her childhood dream of flying planes for a living.

After almost a decade as a physiotherapist, her aviation career is now ready to take off.

The 36-year-old from Lancashire in the north of England has just been offered a job as a pilot by UK carrier EasyJet, joining a small but growing number of women around the world flying commercial aircraft.

Once seen as a very male job, Claire says that attitudes have thankfully changed over the past two decades.

"On leaving school it [becoming a pilot] wasn't really an option for me, there was very little information, and the perception was that women didn't fly aircraft," she says.

"But the industry is now working hard to change that perception, and they're making the career accessible to absolutely everybody."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWith the global aviation industry warning of a shortfall of pilots as demand for air travel rises strongly, recruiting more women could go a long way to solving the problem.

Worldwide air passenger numbers are expected to increase by 6% in 2019, to a record 4.59 billion, according to the International Air Transport Association (IATA). Looking further ahead it predicts that levels could reach 8.2 billion by 2037, led by demand in China, India and Indonesia.

Boeing, the world's largest plane-maker, says that if passenger numbers do rise to that amount, an extra 635,000 commercial pilots will be needed over the next 18 years.

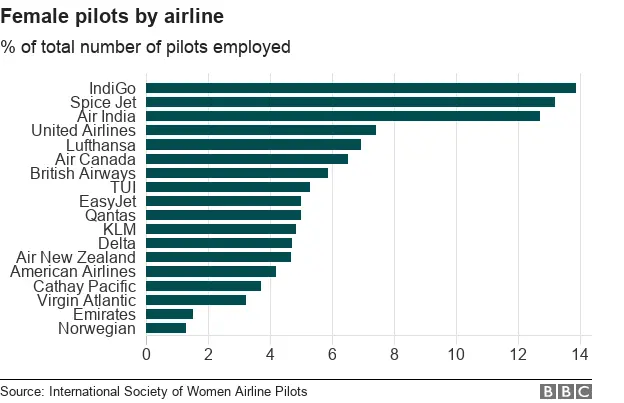

At the moment just 5% of airline pilots are women, according to the International Society of Women Airline Pilots (ISWAP).

That number will need to increase to meet the industry's expected growth, says Robin Glover-Faure, president of L3 Commercial Training Solutions, one of the world's biggest trainers of pilots. L3 trains pilots for more than 40 airlines, including British Airways and Qatar.

Mr Glover-Faure says that to meet the requirement for new pilots "we're going to have to appeal to a more diverse group of people that have got the talent but come from backgrounds where maybe they haven't considered being a pilot before".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe company is also putting money into finding more female pilots through a scholarship scheme. It is now helping 10 women a year fund the training, which normally costs in the region of £100,000, and can take up to 24 months.

Most airlines now require would-be pilots to pay to do such courses, but often with the guarantee of a job once they have completed it. Recruits such as Claire Banks use savings, or borrow money from parents. Other people take out loans.

Some carriers, such as Air France, however, cover the cost of training new pilots.

Mr Glover-Faure says that in the long term, finding more female pilots means breaking down "some of the perception barriers" by going to schools and recruitment fairs to explain that being a pilot is an option for a "very diverse group of people".

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEasyJet, which is one of Europe's biggest airlines, is also actively trying to recruit more women as pilots.

David Morgan, its director of flight operations, is in charge of pilot recruitment. He says there is currently "an acute shortage of females coming into the industry".

To do its bit to rectify this, EasyJet is now aiming for 20% of its new pilots to be female by next year. Currently only 5.4%, or 215 of its total 4,000 pilots, are women.

Another carrier that is working hard to get more female pilots is Virgin Australia. It has set itself one of the toughest targets for new recruits - aiming to have a 50:50 gender balance for its cadet pilots.

Lucinda Gemmell, head of human resources at Virgin Australia, says that out of its latest intake of 16 pilot cadets, nine are women.

The airline says it is proud to have improved on two women out of 10 in its previous class, and Ms Gemmell adds that Virgin Australia wants "to ensure that our workforce is representative of the communities in which we live, work and fly". At the last count only 5.7% of its pilots are women.

Speaking in a personal capacity, ISWAP's Kathy McCullough says that more has to be done across the industry to help female pilots balance their careers with motherhood.

She adds that change is needed to lower the number of women who give up flying so that they can take care of their children.

EasyJet's David Morgan says that his airline offers flexible working patterns.

"Many of our female pilots are on part-time contracts, or on a flexible working pattern where they can accommodate both their professional life and also their home life," he says.

Global Trade

Kathy McCullough adds that a more serious industry-wide problem is that some female pilots have reported sexual harassment.

For widespread change to happen she thinks the aviation industry needs its own #MeToo moment, and that "more women need to speak out about the harassment that they've received".

However, she adds that the problem they face is that "it's perceived as whingeing".

It wasn't until the mid-1970s that major American airlines began recruiting female pilots, and Mrs McCullough says the "dismal numbers" of female pilots 40 years later is the proof that issues have not been adequately addressed.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWhile the wider societal #MeToo movement started in the US, its airlines lag behind many around the world when it comes to numbers of female pilots.

At the biggest three US carriers by passenger numbers, 4.2% of American Airlines' pilots are female, compared with 4.7% at Delta and 3.6% at Southwest, according to ISWAP.

By comparison, at least 10% of pilots are female at eight major Indian airlines. Other carriers that reach double figures are Qantas Link in Australia (11.6%), Iceland Air (10.9%) and South African Express (12.1%).

IATA is now working on what it calls a "major study" that aims to identify the best ways to recruit, retain and promote women in aviation.

New EasyJet pilot Claire Banks says: "The fact that there is a pilot shortage provides a really good opportunity to get that information out there, and really drive the initiative that females can be commercial pilots."