The bar where your cash is worthless

BBC

BBCCashless establishments may be safer and more convenient, but are they more popular with the public at large?

After yet another break-in at south London pub the Crown and Anchor, Arber Rozhaja decided enough was enough.

Burglars were after cash lying around after lock-up, but what if there was never any cash on site at all?

Mr Rozhaja, operations director at the pub's parent firm, London Village Inns, calculated the volume of cash transactions and was bowled over.

"Somewhere in the region of 10-13% of the total revenue would be cash and the rest was card," he says.

So in October, the Crown and Anchor went fully cashless.

Customers can use debit cards, credit cards and contactless payments including Android Pay and Apple Pay. But a fiver will get you nowhere.

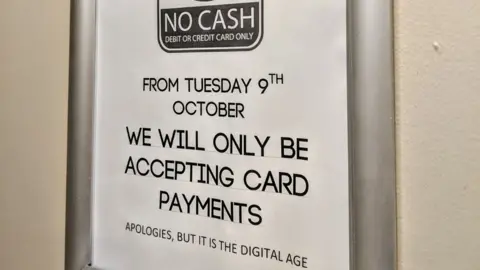

Signs dotted around the pub announced the move to customers: "Apologies, but it is the digital age."

Four of the firm's pubs now refuse cash, with the remaining two set to turn their backs on notes and coins in the New Year.

What began as a move to deter thieves has turned out to be a timely business decision, according to Mr Rozhaja.

For staff at London Village Inns' businesses, the benefits of working in a cashless public house include not having to count up endless piles of coins at the end of the night. And managers no longer need to travel across town with bags of cash to be lodged at the bank.

There are even additional charges to processing cash transactions versus digital ones, says Mr Rozhaja.

He adds that while he's had a few complaints from customers, the response has generally been positive. There has been no discernible fall in business.

"It's a short time for me to have a proper analysis but if it was bad you would see straight away," he says.

But is cash dying out in the UK? And what about the rest of the world?

It was only in September that a pub in Suffolk claimed to be the first in the UK to go cashless. A string of "cashless cafés" has cropped up in Britain, too.

And establishments that turn down "hard" currency are becoming more common all over the world.

Take the trendy eateries in New York, for example, which say "no" to readies. Or the new supermarket in Singapore where robots pack your bags and banknotes are futile. Even Ikea in Sweden has experimented with a cashless outlet.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesCash, as Mr Rozhaja found, is often a hassle. And if it accounts for a negligible fraction of turnover, why not drop it?

Ikea found that so few people - 1.2 in every 1,000 - insisted on paying in cash that it was financially justifiable to offer them free food in the shop cafeteria instead.

"It's slightly surprising to me that there aren't more of these cashless places already," says Dave Birch, director of payments at Consult Hyperion, a research consultancy.

He feels that some societies are embracing the cashless revolution more quickly than others.

"I was in Australia last week where the use of contactless is near ubiquitous. In fact, if you don't tap to pay for something it's regarded as rather strange already," he explains.

Getting rid of cash frees up retail staff so they can spend more time with customers, adds Mr Birch. And tills stuffed with grotty banknotes don't clutter up serving space.

UK Finance, a trade association, projects that in Britain cash will be used in just one fifth of all sales by 2026. In the last year alone, 4,735 cash machines have disappeared, according to research by Paymentsense.

But although cash may be taking a drubbing in some quarters, it remains stubbornly resistant.

"Some [customers] prefer cash for reasons of privacy and security," a recent report notes. "Others live in areas where poor cellphone coverage and frequent electricity outages make cash the most reliable way to pay."

It chimes with a recent survey carried out in the UK, Australia, Brazil and South Africa by currency exchange company Travelex. The research found that about a quarter of people would always refuse to go cashless - despite technological changes and the rise of digital payments.

"Cashless technologies will not replace cash completely... people are happier with an equilibrium between the two," Travelex notes.

In many countries in Europe, the volume and value of ATM cash withdrawals is falling - but in some places the figures are rising.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWherever the use of cash remains high, businesses may find that there are regulatory or legal barriers to going cashless.

In July, for example, China's central bank said that companies and individuals should not refuse cash from customers. And in early December, Chinese retailer Hema was reprimanded by the bank for only accepting digital and card-based payments.

China is an interesting case study.

While city centres are rapidly embracing new technology and the affluent middle class may be happy to go digital, according to McKinsey the country is still an "emerging" market in terms of cashless payments. More than 80% of Chinese retail transactions are still cash-based.

There are also ethical considerations.

Some argue that cash-free establishments are discriminatory as they make it more difficult, or impossible, for homeless customers or those without bank accounts to shop there. Such concerns have led to legal challenges against cashless establishments in the US.

So is Mr Rozhaja worried about putting off people from a low or no-income background?

"No, it's easy to get a prepaid cash card online. Especially in London, I don't think it's possible for you to operate if you don't have some sort of a card," he says.

But tensions around the issue mean that societies should now be trying to put in place cost-effective infrastructure for digital payments "for everyone", says Dave Birch.

So while cash is undoubtedly declining, it is certainly not on its deathbed yet.

"A cashless society is not a society that literally has no cash in it," concludes Mr Birch. "It's a society where cash is economically irrelevant and I think we're heading towards that."