How safe are my savings after the financial crisis?

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibrarySavers - like the wild reindeer of Russia's Taimyr Peninsula - move for protection.

Rising temperatures and human activity have changed the migration patterns of the world's largest wild reindeer herd. The threat of mosquitoes pushed them higher and further north to cooler ground, as their numbers fell.

Amid the financial crisis, savers moved too - in their droves - worried about falling numbers of a different kind.

The collapse of Lehman Brothers, and the subsequent bailouts of Royal Bank of Scotland and Lloyds/HBOS made them worried about the safety of their savings.

So they moved to a safer place. They divided their money and put their cash in government-backed institutions such as National Savings and Investments (NS&I).

Savers' flight to safety was one of the most obvious reactions to the banking and financial crisis. Now, 10 years on, how safe is their money and how has protection changed?

How did the crisis affect your finances?

Homes: House prices in London and the south east may have risen sharply in the decade since the crisis. But in large swathes of the UK prices have still not recovered to the levels seen in 2008.

Savings: The last decade has been a disaster for Britain's savers, especially many elderly people who rely on their savings income. Savers who once enjoyed rates of 5%-plus now get a fraction of that.

Borrowing: Average household debt has climbed from less than £3,000 to £4,000 in the last decade. There are lots of reasons for this, not least the easy credit available through plastic cards.

Banking: The way we bank has completely changed. Challenger banks have emerged, and mobile technology means we increasingly sort our finances using phones. But online banking has brought branch closures - and cyber-attacks.

In 2007, customers queued outside branches of Northern Rock worried that their savings would disappear amid the first run on a British bank for more than a century.

The government stepped in and the nationalisation of the North East-based bank meant no savings were lost.

The following year and the collapse of Lehman Brothers marked the start of the global financial crisis in earnest. The fears of those Northern Rock customers were mirrored among the wider saving public.

Customers ploughed money into NS&I, which runs Premium Bonds and a variety of savings products, and the now 100%-secured Northern Rock, because they saw them as a haven for savings. NS&I reported inflows of £26bn in the 2008-09 financial year.

In fact, there was already a safety net in place, but it was not widely recognised and not widely understood.

The safety net

The Financial Services Compensation Scheme (FSCS) protects a certain level of savings if a bank, building society or credit union goes bust. The scheme is funded through a levy on the financial services industry.

During the run on Northern Rock, the safety net only guaranteed 100% protection of the first £2,000 of savings and 90% of the next £33,000 per person, per institution. This was the equivalent of protecting £31,700.

Mark Neale, who has been the chief executive of the FSCS since 2010, said it was "rational" for people to queue outside Northern Rock to withdraw their money.

"The protection then would have left them with losses, so it was rational to question how safe their money was," he said.

PA

PAThe response from the government was to increase protection to the whole of the first £35,000 of people's savings, then a year later protection was increased again to £50,000.

At the height of the crisis, Mr Neale was on the senior management team in the Treasury.

He describes the atmosphere at the time as frenetic, with "all hands to the pump".

Yet, among the public, savers were becoming better protected and so less prone to panic, he argues. By mid-2009, NS&I announced that savers' flight to safety was over.

The FSCS was needed as the crisis developed. When Bradford and Bingley had to be rescued at the end of September 2008, it had to protect customers' savings.

The failure of some Icelandic banks, popular among UK savers, meant it was called on again.

Those two events meant four million savers were protected at a cost of £20bn - money that was subsequently recovered with, for example, the sale of Bradford and Bingley's buy-to-let mortgage book in 2017.

Ten years ago, it could take weeks for deposits from failed banks to be returned to savers. Now it can be done within a week.

The amount protected improved too. A link was then established with European protection, meaning that by the end of June 2009, the first £50,000 or €50,000 (whichever was higher) was protected.

At the end of 2010, protection rose to its current level of £85,000 per person, per institution, although the strength of sterling meant that during 2016 it was reduced to £75,000, only to return to £85,000 when sterling weakened. Joint accounts now have a protection level of £170,000. The current level of protection in Europe is €100,000.

Mr Neale says that the public is much more aware of these protections. Research for FSCS suggests that more than 80% of the UK population know about savings protection.

"If there is another failure like Northern Rock, they should not be rushing to pull their money out. They know we will get it back to them," he says.

"But we must be ready for another crisis. We also need to keep pace with the changing ways that people are saving their money."

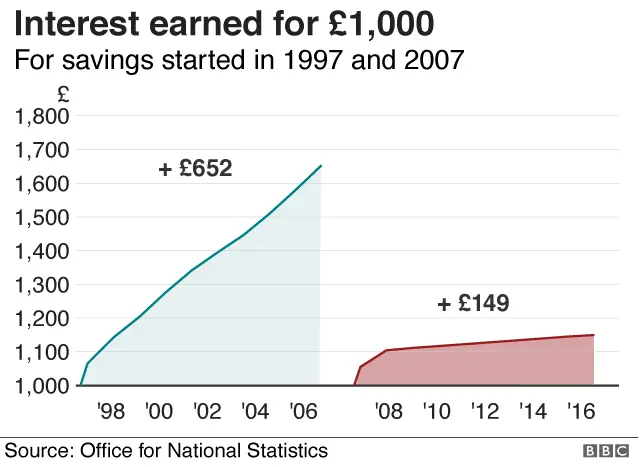

Savings may now be better protected than they were at the start of the financial crisis, but they are not better rewarded.

In September 2008, easy access savings accounts at the top of the best buy tables were offering interest of 6.5%. Now the equivalent best returns are 1.4%.

The financial crisis has led to a decade of low interest rates, but it also led to schemes aimed at kick-starting lending which have hit savings rates. The most significant was the Funding for Lending Scheme, launched in 2012, which provided funding to banks for an extended period.

"Lenders were given a cheaper source of funding for their loan book and, as a result, no longer needed to raise money from savers," said Susan Hannums, co-founder of independent savings website Savings Champion.

"The knock-on effect was that as best buy rates were cut, the legacy back books were paying rates that were too competitive, so there began a torrent of rate cuts to existing savings accounts."

It may be many years until the pre-crisis savings rates return, but the money that is deposited is now much better protected.

Protection explained

The first £85,000 per person, per institution is protected under the FSCS which has a protection checker for savers.

Protection above this limit is available for those who have a sudden influx of funds owing to a life event such as a divorce settlement, inheritance or pay-out from a life insurance policy. The "Temporary High Balance" protection covers deposits over £85,000 and up to £1m per institution for up to six months.

This protection is designed to give savers a breathing space to plan what they wish to do with their lump sum.

All these rules offer protection per person, per banking licence. Most bank brands will have a separate banking licence but some share one. Protection is limited to £85,000 in total for anyone with multiple accounts in banks with one licence between them.