'There are boats floating above my head in Times Square'

BBC

BBCAugmented reality (AR) - adding a digital overlay to a real-world image - is giving artists and galleries opportunities to create more interactive artworks and exhibitions, providing more exciting experiences and reaching new audiences. But until AR headsets become widespread - and fashionable - will this remain a niche technology?

Imagine holding your mobile phone up in front of Pablo Picasso's Woman with Green Hat and seeing the portrait transform into a photo of the muse who inspired the painting.

Or admiring one of Claude Monet's many famous depictions of water lilies, only to see the image morph into video footage of the artist's real flower garden in Giverny, the inspiration for this series of paintings.

It is how visitors to Vienna's Albertina Museum can experience its current Monet to Picasso - The Batliner Collection exhibition.

AR is changing the art world, allowing artists to fuse physical art with digital content. New work is being created and existing work re-imagined.

"Trying to learn about art and its history can be intimidating because of its complexity," says Codin Popescu, chief executive and founder of Artivive, the firm behind Albertina Museum's AR experience.

"For our projects with museums, we decided to offer visitors additional information - sometimes in a playful way through an animation or by showing historical footage of the time."

Artivive

ArtiviveIn February, Manchester Central Library hosted AR fine artists Scarlett Raven and Marc Marot who used AR to weave poetry, animation and music into an exhibition about World War One.

"Many of the oil paintings were quite vibrant, which gave them an uplifting feel at first glance, but as soon as the AR came to life I realised that the scenes before me were where past horrors had taken place," says Fiona White, a visitor to the exhibition.

"The AR wasn't just visual, there were voiceovers, music and storytelling that gave a whole history to the artwork that would otherwise go unknown."

The tech has great educational potential, especially for the smartphone generation, believes Manon Slome, co-founder of No Longer Empty, a New York-based exhibitions curator.

"You are using a language and medium with which many more people are comfortable, and you don't need an art history degree to apprehend the work," she says.

In a current installation, which runs until 5 September in New York's Times Square, the city's Queens Museum collaborated with No Longer Empty and Times Square Arts to create Wake and Unmoored, a two-part AR installation aiming to educate the public about climate change.

Artivive

ArtiviveDesigned by artist Mel Chin, the installation makes visitors feel like they are under the ocean.

"Unmoored looks to a future where climate change has gone unchecked and [the city] is underwater due to rising sea levels," says Ms Slome.

"What better way to imaginatively capture this projected reality than through a technology of the future? Seeing ships floating over one's head really puts such a future into visual but engaging terms."

And last year, San Francisco's Museum of Modern Art (SFMOMA), in partnership with frog design, launched a Magritte Interpretative Gallery as part of its exhibition on surrealist artist René Magritte.

The gallery houses six AR interactions, enabling visitors to investigate Magritte's themes through a series of altered and augmented windows.

One of the installations involves a video likeness of the viewer being transmitted from one glass window to another.

"Friends and strangers will joyfully run over and show the unsuspecting subjects where their images have popped up," says Chad Coerver, SFMOMA's chief content officer.

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art"It's a gentle, fun reminder that nothing is what it seems in a Magritte exhibition."

But the unwieldiness of AR tech has been an obstacle for both artists and consumers, and some believe this will always limit its potential.

"For a start, having to install a new app to be granted the full experience of an art gallery is a barrier many may not cross," says Tom Ffiske, editor of immersive technology website Virtual Perceptions.

"Why fiddle with new tech when most people can just enter an art gallery and use their own eyes?"

Despite this, AR is stealthily creeping into our everyday lives.

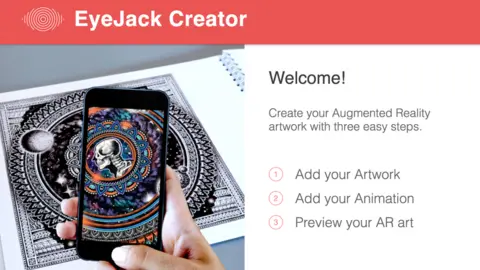

"Since Snapchat and Messenger introduced their AR facial recognition, millions of people around the world have been experimenting with AR pop art before even knowing the term 'augmented reality'," says Sutu, artist and co-founder of EyeJack, an app and platform for the curation and distribution of augmented art.

Reuters

ReutersLong-awaited AR glasses, being developed by the likes of Intel, Magic Leap, Lumus and Osterhaut Design Group, could make for a more seamless experience.

For artists, the need for technical nous has presented challenges.

"Much of the work that artists will look to produce will require a knowledge of 3D design programs such as Unity, so that's a barrier to entry," says Alex Poulson, chief executive of London-based AR firm Inde.

"AR on mobile devices is beginning to see some adoption, but the technology itself is still in its infancy."

But things are changing fast.

EyeJack

EyeJackThe recent release of AR developer platforms by Google and Apple is enabling the creation of new apps for Android and Apple devices, potentially making it easier for artists to create their own AR art.

And tools like Artivive help overcome the knowledge barrier.

"For artists to create art in augmented reality they previously had to build their own isolated solutions, which required technical skills and resources. But with Artivive, those artists can focus on their creative work," says Sutu.

AR is also opening up new revenue streams for artists.

One artist sold an AR artwork with the agreement to supply the buyer with a new digital layer every six months for four years, says Artivive's Mr Popescu.

More Technology of Business

"The artist basically sold the buyer a digital art subscription model along with the physical artwork."

AR opens up commercial opportunities for museums and galleries too, allowing them to hold concurrent exhibitions in one physical space, using digital reinterpretations of the same artworks.

While Mr Ffiske "cannot see [AR] becoming anything more than a niche art form that pushes boundaries", Ms Slome is more forthright.

"Once you've glimpsed the future, there's no turning back. Get used to it."