Who's winning the global race to offer superfast 5G?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSuperfast "fifth generation" (5G) mobile internet promises download and browsing speeds 10 to 20 times faster than we have now. In the first of a new series of articles and videos, BBC News examines the international race to be first to launch and cuts through some of the hype.

It's the World Cup of telecoms. The nascent technology known as 5G is currently being promoted by companies and governments as a transformative high-speed boost for wireless connectivity.

Although it is not yet fully defined as a standard, we are told that high definition (HD) films will soon download to smartphones in seconds, or that driverless vehicles will beam swathes of data to control centres and each other as they navigate smart cities.

But what is the reality of 5G today? Which nation has got the most out of it so far? And is it all it's cracked up to be?

The most significant showcase for 5G so far was made earlier this year in South Korea during the Winter Olympics.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe Koreans used nippy wireless connections for a number of applications - including, bizarrely, the connection of deterrence devices in the countryside designed to keep wild boars away from the Games. Some of the devices were set up to play tiger roars in an effort to ward off the roaming pigs.

In a use that may be more widely applicable in the future, local operator KT also used 5G to beam live video of events to giant screens on buses.

All of this was roundly applauded at the time, but if you cut through the hype, you quickly stumble on honest admissions from KT that its 5G experiments had some limitations.

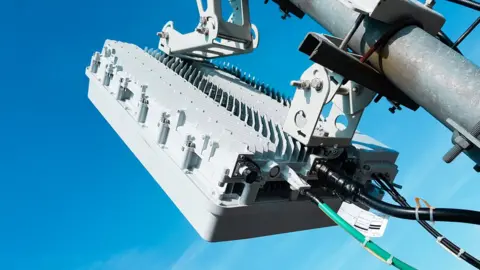

At a summit in New York in April, a KT representative said four times as many base stations - antennae beaming the signal - are needed for 5G compared to LTE, the current generation 4G technology.

The Olympics trials were hampered by poor penetration of the 5G signal to indoor spaces when broadcast from outside, he added. KT will have to invest capital to try to solve such issues.

Getty Images

Getty Images"You get the feeling that South Korea, having had this strong push, is now pausing for breath," says Prof William Webb, independent consultant and author of the book, The 5G Myth.

Prof Webb points out that 5G can operate at a number of different frequencies. Higher frequencies known as "millimetre waves" may offer faster data rates of about 10 gigabits per second (Gbps) or more - but they cover much narrower ranges and are far more easily blocked by buildings, windows, and even people walking in front of them.

Those ultra-fast 5G frequencies of about 28 gigahertz (GHz) and above, which South Korea used for some of its trials, are particularly difficult to implement.

While an honourable mention should go to Qatar, whose telecoms provider Ooredoo says it has already launched a commercial 5G service, the global race is being dominated by the big boys.

The US, for example, has been charging ahead with trials and experiments. Major network operators such as AT&T and T-Mobile have been buying up technologies and bits of the radio spectrum to allow for small-scale 5G roll-outs.

But, as Prof Webb says, there's often very little detail in the many press releases as to how coverage will actually be implemented.

EE

EEFor example, AT&T recently announced that a dozen US cities would get 5G coverage this year. But in its press release, there is no mention of frequency bands or how base stations will be arranged to provide the signal.

Earlier this year, AT&T acquired a firm that had been experimenting with the millimetre wave spectrum. But Prof Webb suspects that AT&T would transmit data at those high rates across only limited parts of its network, meaning many with 5G-enabled smartphones wouldn't enjoy the highest speeds.

What kind of signal coverage people will get with such roll-outs offered by operators like AT&T, T-Mobile and Verizon is not yet clear. But US firms are clearly eager to get some kind of 5G off the ground by the year's end.

More Connected World features

Prof Rahim Tafazolli at the University of Surrey thinks the UK has a decent chance of being among the first nations to roll out successful pockets of 5G - but these may be highly localised.

"We think that the cost-effective deployment will be in areas where we need ultra-high capacity - for example football stadiums connecting thousands of people," he says.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn other words, signals might be stronger in certain locations to cope with a dense mass of people all carrying mobile devices.

There are also efforts, led by UK government-funded test bed RuralFirst and Strathclyde University, to bring low and medium frequency coverage to more remote areas. Again, though, it's very early days and the project seems to be more about getting better coverage to those areas than ramping up download speeds.

Still, Prof Tafazolli exudes confidence.

"In the World Cup we are among the top four countries," he says. "In 5G we are within the top five countries in the world."

China has spent lots of money investing in early 5G trials and has sped ahead of the US, according to a recent report by consultancy Deloitte. It has outspent the US by $24bn since 2015 and has built 350,000 new cell phone tower sites, compared to about 30,000 in the US.

And corporations in China are planning on a large scale, apparently jostling for global domination in 5G.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThis involves the filing of many patents by tech firms in the country and, for example, the signing of memoranda of understanding between Huawei and many foreign telecoms operators.

Some think it is all part of a Chinese strategy to be the first to roll out significant deals once 5G tech is actually finalised. If you're concerned about global competition, China is clearly a player to keep an eye on.

"All major Chinese providers have committed to specific launch dates," said market research firm Analysys Mason earlier this year.

"And the government has committed to at least 100MHz [megahertz] of mid-band spectrum and 2GHz of high-band spectrum for each wireless provider.

Japan is also spending big.

In March, some visitors to a 30,000-capacity baseball stadium in the country were able to watch live 4K video streamed to tablets that could receive millimetre wave signals.

But behind all the national thrusting for 5G leadership is a more sober reality, says Brendan Gill at mobile data analytics firm OpenSignal.

"A lot of people aren't on 4G networks," he says.

Improving 4G coverage - which can still let users stream HD video - is perhaps a more important endeavour right now than introducing a brand new technology that has extremely specific use cases, he says.

In fact, Mr Gill describes the difference between 4G and most 5G applications as "incremental".

Why all this hype then? Well, there seems to be an international race on. And no country likes to be last.