How the US is waging its trade war with China

Getty Images

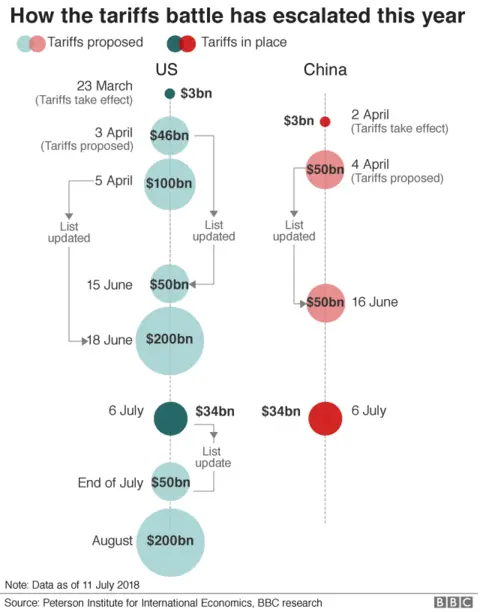

Getty ImagesAfter US tariffs on $34bn (£25.7bn) of Chinese goods came into effect last week, China is very much in President Trump's firing line.

More is coming: details of another $16bn worth are already in the pipeline and President Trump has ordered the administration to prepare to collect tariffs on £200bn of Chinese trade on top of that.

China's trade policy is unfair, he argues, and it steals the technology of American businesses.

Trump's position is shared by his trade adviser Peter Navarro, who co-wrote a book, Death by China, which was also made into a documentary film. Mr Navarro warns of the threat he thinks that China poses to US interests.

The bare figures of China's rise as a trade power are certainly striking.

The country exports almost seven times as much as it did at the start of the 21st Century.

It is the world's biggest exporter of goods, worth more than $2tn a year.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut it is also a leading market for other countries. China ranks second as an importer of both goods and services.

China does however do more of the former - exporting - than importing. There is a substantial imbalance in its trade with the rest of the world.

Using a somewhat wider measure, called the current account of the balance of payments, which includes trade, China had a surplus last year of $165bn.

That is large, but it's not the largest. Germany and Japan have bigger surpluses, and President Trump has taken issue with them as well.

President Trump often focuses on these international commercial imbalances, seeing them as a sign that trade agreements signed by his predecessors are unfair, and that other countries are taking advantage of the US.

China's surplus has in fact declined to well below half what it was in 2008. If you focus on the surplus as a percentage of national income or GDP the decline is even more marked - from just below 10% in 2008 to 1.4% in 2017. By that measure it is now a rather moderate imbalance.

The US, by contrast, has a trade deficit with the rest of the world, to the tune of $800bn last year for trade in goods. The largest bilateral deficit was with China at $375bn.

These imbalances are significantly smaller if you include trade in services (such as finance, business services and travel) where the US is the world's biggest exporter, though President Trump has a tendency to overlook that. He tends to focus specifically on trade on goods.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt's a matter of debate how much these imbalances matter, and whether they are the result of countries' trade policies.

Most economists would tell you that a country's overall trade balance is the result of savings and investment by business and households, and government tax and spending policies; that it is not determined by trade policies.

A country that spends more than it produces will have a trade deficit, such as the US.

One that earns more than it spends will have a surplus. China, with very high levels of household savings, is one example.

That does not mean that government policies aren't a factor. Tax and spending policies, interest rates, exchange rate policies, and labour market policies can all affect savings and investment and the trade balance.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut it is not, most economists would say, driven fundamentally by trade policies.

It must be said that this is counterintuitive, and it is not a view shared by President Trump. He tends to see the imbalance as the result of China's trade and other policies including subsidies, currency manipulation and the acquisition of others countries' technology.

His administration was particularly critical of the "Made in China 2025" initiative, under which Beijing wants to strengthen the country's position in a number of key advanced sectors of industry, including pharmaceutical products, aircraft and robotics.

The Office of the US Trade Representative has described it as part of a plan of "seizing economic dominance of certain advanced technology sectors".

What is beyond dispute is China's giant economic presence.

There was a key moment in China's rise early in the present century, when it joined the World Trade Organization.

That mean that China's access to overseas markets - such as the levels of tariffs it faced - was protected by the WTO's rule book.

President Trump believes that was a mistake, that there was a missed opportunity to force China to open its own markets.

A 2017 report to Congress from the US Trade Representative wrote: "It seems clear that the United States erred in supporting China's entry into the WTO on terms that have proven to be ineffective in securing China's embrace of an open, market-oriented trade regime".

Global Trade

More from the BBC's series taking an international perspective on trade:

The US is now continuing to hit back, with last week's wide-ranging tariffs, and this week's announcements, coming after existing levies on imports of Chinese steel and aluminium.

Regarding these two metals there is excess global capacity, which reflects, at least in part, the investment China has made.

Since the turn of the century China's steel production has increased six-fold, although it did decline slightly in the past few years. China's aluminium production has increased even more rapidly.

US concerns about China's metals production, and Beijing's approach to acquiring foreign technology, are shared by a number of other leading trade powers, including the European Union. and also by previous US administrations.

The EU has often pressed China to tackle what it considers its excess steel and aluminium capacity, and complained to the WTO about much the same intellectual property and technology issues.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesGeorge Magnus, of the China Centre at Oxford University, says that President Trump has a point in relation to China's industrial and commercial policies.

Foreign companies wanting to operate in China have to work with a Chinese partner in a way that means they can easily lose control of their technology.

He highlights China's advances in high-speed rail and electric vehicles.

Where the EU and others part company with President Trump is in his enthusiasm for unilaterally imposing additional trade barriers on China. Needless to say, they are even less enthusiastic about the steel and aluminium tariffs, which are also hitting US allies.

Another allegation often levelled at China is that of manipulating its exchange rate to gain a competitive advantage. A cheaper currency makes it easier for a country to sell its goods abroad.

It was a more widely held concern in the last decade, but the Chinese currency has risen since then, taking away some of that competitive advantage.

That said, it is a weapon that China could possibly use as it continues to respond to the US tariffs on its goods.