The man who created a $2bn ice cream firm in his kitchen

Halo Top

Halo TopThe BBC's weekly The Boss series profiles a different business leader from around the world. This week we spoke to Justin Woolverton, the founder and chief executive of ice cream brand Halo Top.

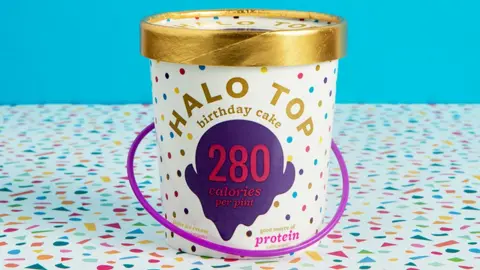

Just a few years ago Justin Woolverton was pleading with US supermarkets to keep his reduced calorie ice cream tubs in their freezer cabinets.

Sales of his low fat, low sugar brand Halo Top were flat-lining, and stores were continually threatening to stop stocking it.

"We were hanging on by the skin of our teeth," says the 38-year-old, who launched the business in 2012. "We'd tell them 'leave us up there, things are going to turn around'."

In his wildest dreams Mr Woolverton couldn't have predicted just how dramatic the turnaround would be. Just six years after starting, his ice cream is now the best-selling brand in the US.

With very little money for marketing, the LA-based start-up had been trying to inch up sales by working hard to promote itself on social media.

Halo Top

Halo TopThen in 2016 a journalist for GQ magazine wrote a very witty article about how he ate only Halo Top ice cream for 10 straight days.

The story went viral, and Halo Top's sales went through the roof.

In 2016 it was reported to have sold 28.8 million tubs, generating $132.4m (£101m) in revenues becoming the best-selling pint of ice cream in the US, beating iconic industry leaders such as Ben & Jerry's and Häagen-Dazs.

Not bad for a small independent business that has no outside investors, other than the family and friends of Mr Woolverton and his co-founder Doug Bouton.

Yet despite the brand's success, some critics have questioned the claimed health credentials of the "guilt free" ice cream. While others wonder if it should be allowed to call itself ice cream at all.

Ben & Jerry's

Ben & Jerry'sBefore founding Halo Top, Mr Woolverton was working in Los Angeles as a corporate lawyer, a job with which he'd become disenchanted.

The idea for the ice cream came about because of restrictions he made to his diet to manage his blood sugar levels.

At home, instead of sugary treats, he'd have a bowl of Greek yogurt with fruit, to which he would add the sweetener stevia.

After buying a $20 ice cream maker he put the mixture through it to see what it would taste like. "It was delicious. So from there, it was like: 'Holy cow, if I like this why wouldn't other people like it?'."

Mr Woolverton then started experimenting with ingredients, including replacing the yogurt with milk, to make the concoction behave more like ice cream when frozen and enable it to be produced on a mass scale.

"It honestly took a year of complete failure at the beginning," he says.

Oppo

OppoWith friend Doug Bouton, another former lawyer on board, they launched the business with money borrowed from family and friends, student loans and £150,000 of credit card debt.

Mr Woolverton says that not having any private equity investors has given him and Mr Bouton more freedom. "We don't have suits telling us what to do," he says.

To promote the brand on social media in its early days, Mr Woolverton came up with a novel idea. He hired local college students to send Halo Top coupons to people with large followings on YouTube and Instagram who were posting about health and fitness.

"That was a really big marketing strategy," he explains. "We thought if they can buy it that's great; if they can't, we're on their radar anyway."

Alex Beckett, global food and drink associate director at research group Mintel, says that Halo Top's continuing strong use of social media has been a key component behind its success.

"It enhanced its appeal as a cool, plucky alternative to global ice cream brands with larger advertising budgets," Mr Beckett says.

And then there was the GQ article.

"That [Halo Top diet] is not something we recommend, to be clear, but it was a really fun article," says Mr Woolverton. "It made the brand catch fire."

More The Boss features, which every week profile a different business leader from around the world:

After the story went viral, Halo Top enjoyed a rise in sales so meteoric that the business struggled to keep up with demand.

"[Supermarkets] didn't know how to deal with it either," says Mr Woolverton. "For the first time people were buying three, four or five pints at a time. It had become the first lifestyle ice cream that people could eat daily."

But should people really be eating Halo Top on a daily basis?

The ice cream contains two sweeteners - erythritol and stevia - in place of much of the sugar. While these are widely used across the food industry, and given a clean bill of health by food authorities, they do have their sceptics who say they may cause side-effects, such as exacerbating irritable bowel syndrome.

Other critics claim that Halo Top and its rival reduced-calorie ice creams could actually contribute to people putting on weight. And some question whether Halo Top should be allowed to call itself an ice cream, because it contains so little milk fat.

Halo Top

Halo TopMr Woolverton says the brand's success "is a recognition of how much smarter consumers are than a lot of companies think".

Halo Top's success has also led to the launch of numerous other reduced-calorie ice cream brands. These include Unilever's Breyers Delight, Ben & Jerry's "Moo-phoria" range, and UK start-up Oppo.

Mr Woolverton has also been inundated with takeover proposals, including a reported $2bn offer from Unilever. He has rejected all of them, and instead has his eyes on global domination.

The company launched in the UK last year, and exports to countries including Australia and Singapore. Halo Top ice cream parlours, called Scoop Shops, have also opened in the US.

Mr Woolverton is confident that within five years Halo Top will be one of the biggest ice creams brands globally. "We'll be as well known as Ben & Jerry's," he says.