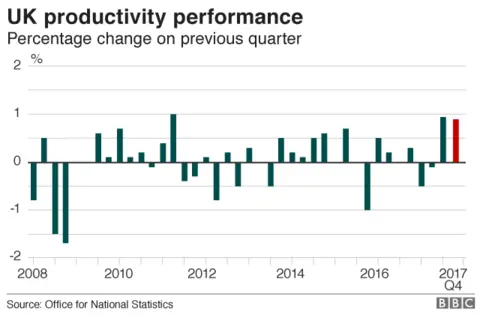

Productivity growth strongest since financial crisis

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe UK has seen the strongest two quarters of productivity growth since the recession of 2008, according to the latest data.

Output per hour rose 0.8% in the three months to December, the Office for National Statistics said. It follows growth of 0.9% in the previous period.

There was also a better than expected rise in wages. Excluding bonuses, earnings rose by 2.5% year-on-year.

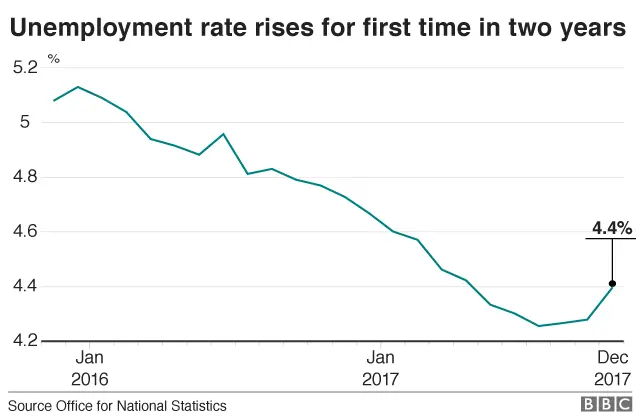

However, unemployment edged higher, but still remains low at 4.4%.

The growth in productivity - as measured by the amount of work produced per working hour - will provide encouragement to policy makers who have wrestled with the challenge of low productivity growth since the financial crisis.

The ONS said the surprise rise in the unemployment rate raised the question of whether the UK's long run of falling unemployment might be over.

The rise in wages still lags behind inflation which stood at 3% at the end of last year. So average pay has not increased in real terms. But a pick up in wage growth is another sign that the UK economy could be shifting tack.

Economists suggest that the rise in wages is significant.

Yael Selfin, chief economist at KPMG in the UK, said: "There are signs that average weekly earnings, which rose by 2.5% in the fourth quarter, are beginning to respond to the tightness of the labour market, although households are still feeling the squeeze when accounting for inflation, with real earnings falling by 0.3%."

She also described the productivity figures as "very encouraging".

"If stronger productivity continues into 2018, the Bank of England may decide to hold at least once on raising rates this year," she added.

Earlier this month the Bank of England indicated that interest rates were likely to go up more quickly than previously expected if the economy remained on its current track. Economist predicted there might be a rate rise as early as May.

The increase in unemployment for the three months to the end of December was the first rise in the jobless rate for two years. However, the total number of people in work also continued to rise, jumping by 88,000 in the same period.

Some of that increase was due to people previously classed as inactive and not looking for work moving into the workforce or registering as unemployed.

"There are mixed messages in the data we've had out this morning," says Liz Martins, senior economist at HSBC.

"You've got a big rise in unemployment, a big rise in employment and a big rise in the workforce. It's not clear any one of those in isolation is a start of a trend.

Ms Martins said she expected the unemployment rate to continue to rise but that rising numbers out of work could be part of the explanation for increased productivity growth.

"If GDP is growing more than the number of people working in it, then productivity will grow as there is more growth per head.

"It's not the nicest way to get productivity but it is effective as long as GDP growth doesn't slow too," she said.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The productivity puzzle

Analysis: Andy Verity, economics correspondent

We used to take it for granted that we would each get better off as the economy grew.

As companies and the government invested in better technology and skills, each worker could produce more goods or services per hour, bringing in more revenue to their employers - and as a result, each worker could be paid more per hour.

Those improvements in productivity were for most of the last 200 years the motor of economic growth, so regular they could be taken for granted.

In the past decade, that engine of improved prosperity broke down.

By June 2017, the amount produced per hour was only 0.4 per cent larger than it had been nine years before.

While we had had economic growth, most of it wasn't growth in the amount each worker produced or earned, but simply growth in the number of people working.

Because an economy is simply people and their economic activity, when the number of people grows, so does the economy. But it may not be the sort of growth where individuals are getting better off.

So used to the "productivity puzzle" have economists become that when the ONS estimated productivity growth of 0.9% in the third quarter of last year, many dismissed it as a blip.

But now, with another estimate of 0.8 per cent in the final quarter, fewer are scoffing. Maybe that old motor has some life in it yet.