Why the young should watch the Budget

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMore young people are voting than at any time in the last quarter of a century.

But that resurgence is favouring the Labour Party.

Just two years ago, the split in support between Labour and the Conservatives among 18 to 29-year-olds was fairly even, 36% to 32%.

But in June's general election that gap widened dramatically, with Labour taking a 64% share to the Tories' 21%, according to pollsters YouGov.

So with the Budget coming up on 22 November, where could the Chancellor take action to attract the younger voter?

Housing

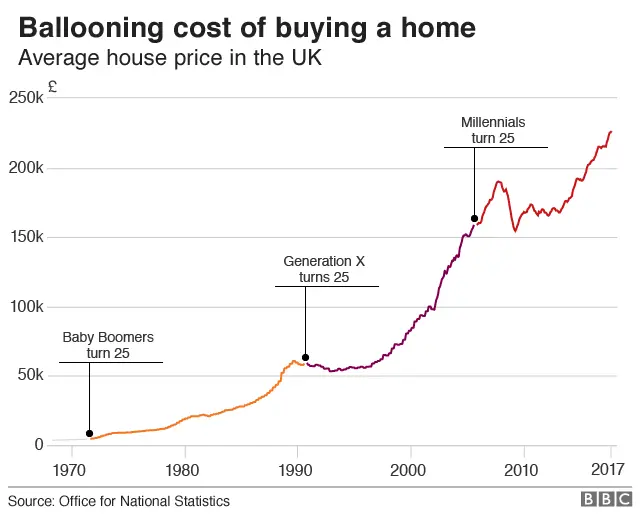

The number of young people living at home has been rising.

In 1996, around 2.7 million, or 21%, of those aged between 20 and 34 were living at home. That figure has risen to 3.4 million or 26% in 2017, according to the Office for National Statistics.

For young men the proportion is even higher, at 32%.

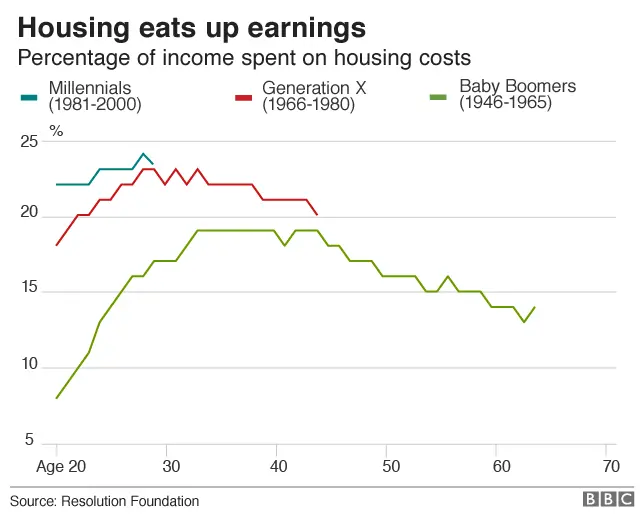

That rise is partly due to more young people staying in education and training, but also due to the increased costs of buying or renting a home.

In October, Prime Minister Theresa May promised to fix the "broken" housing market and earmarked another £2bn to build council houses and affordable homes for rent.

But Labour and housing charities said the plan would only help a fraction of the 1.2 million families awaiting housing.

Pay

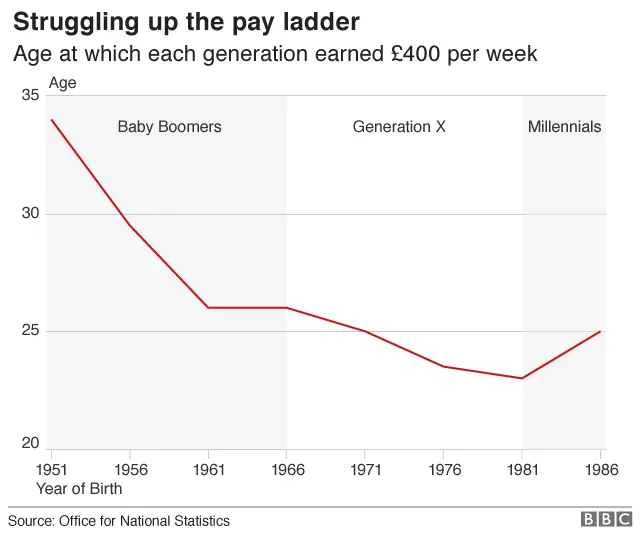

For decades after World War Two young people could expect to be better off than their parents at comparable ages.

But some data shows recent generations have been doing worse than their predecessors.

If you look at the chart below, the age at which Baby Boomers and Generation X, started earning £400 per week consistently fell. But for millennials that age started to rise.

However, more recent data shows that pay for younger people has been holding up well over the past 10 years. Younger generations have seen pay growth that is roughly comparable to older workers, according to data from the Office for National Statistics. Pay for younger workers has been supported by rises in minimum wage.

Education

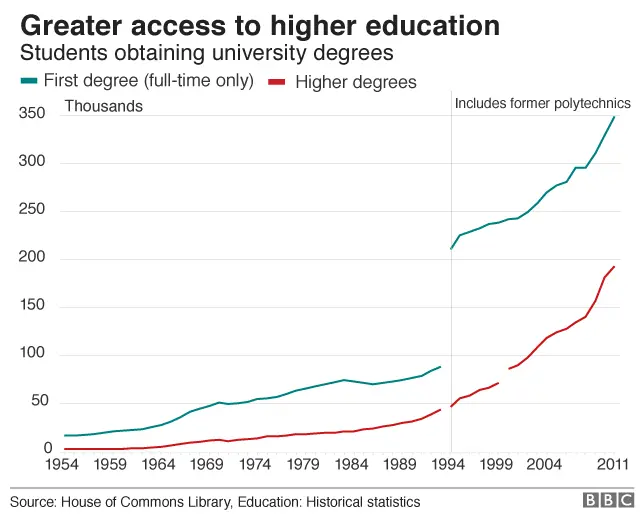

It's not all grim news for today's young people. They are going on to higher education in greater numbers than previous generations.

In 1950, just 3.4% of the population had been to university.

As the chart above indicates, there has been a dramatic rise in higher education participation since then.

In England, the higher education participation rate for 17-20 year olds rose to 42% in 2016, from 33% in 2006.

However, there are questions over whether there is demand for those graduates.

The Chartered Institute for Personnel and Development (CIPD) estimates that for those who left in the 2015 university year, 48% ended up in non-graduate jobs six months on.

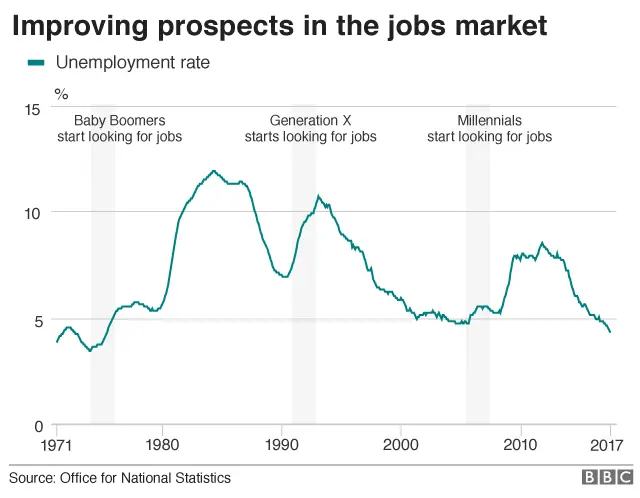

But at least the jobs market is strong. The unemployment rate has fallen to 4.3%, the lowest in 42 years.

Debt

But that higher education comes at a cost. Tuition fees were first introduced in 1998 and since then have risen to more than £9,000 in England. In Scotland young people do not pay university tuition fees.

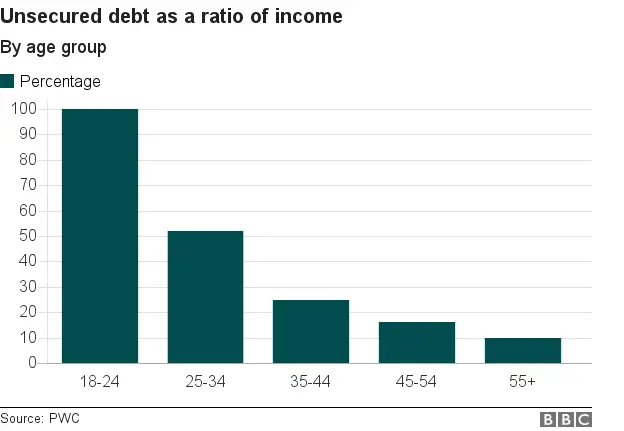

If you include that student debt, then young people have very high levels of unsecured debt.

The chart above is based on recent survey data analysed by PWC. It found that on average 25 to 34-year-olds hold debt equivalent to more than 50% of their income.

Of course you could argue that student loans are not as onerous as other forms of debt, as it is only paid back once the graduate gets a job earning more than £21,000 a year.

Nevertheless, it is a financial burden that previous generations have not had to carry.

In October, the government announced that tuition fees in England would be frozen at £9,250 a year. It will also raise the earnings threshold at which graduates have to start paying tax to £25,000 in April 2018.