Ikea: Why we have a love-hate relationship with the Swedish retailer

Ikea

IkeaMention the word Ikea to anyone and you're guaranteed either a sigh of despair or an enthusiastic grin, but seldom something in between.

The Swedish giant is the Marmite of retail outlets: you either love it or you hate it.

But that hasn't held it back; in the 30 years since it opened the doors of its first UK shop in Warrington, its popularity with British shoppers has steadily grown.

Fans point to the Scandinavian designs at affordable prices, the bold modernist patterns and blond wood aesthetics. Plus the meatballs of course.

But for every lover there's a hater, lamenting the long queues, the labyrinthine lay-out and the flat-pack misery to deal with once you get home, Allen keys, metal bolts, baffling instructions and all.

'Strange concept'

How then has it become so successful, expanding to become the UK's largest furniture retailer by far, with 20 stores and boasting sales growth of 47% over the past five years in the UK? What has kept us going back?

Paul Fishwick, who was one of Ikea's first UK employees in Warrington, says when the chain first opened the reaction from most customers was less clear-cut.

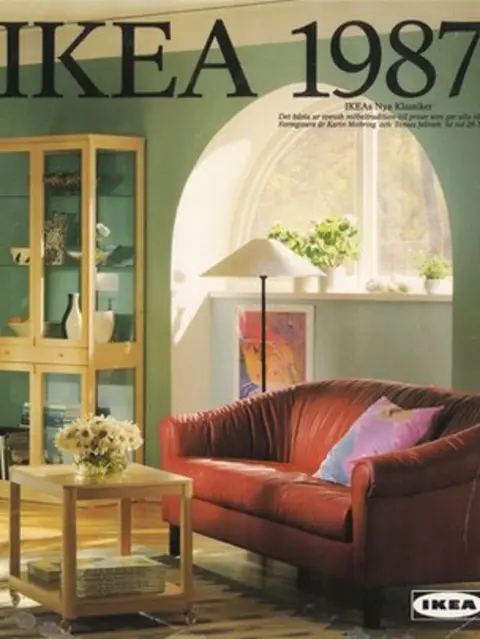

"In 1987 it was a strange concept. A furniture store which acted like supermarket.

"The bulk of people were confused. They said 'can you follow me around and take my order'," he says.

But people still came in their droves. Opening day was "absolutely chocca", he says, with the store's popularity meaning it had to enforce a "100 people out, 100 people in" policy in the early days.

Ikea

Ikea Mr Fishwick, who now works in Ikea's marketing department, says some of the 1980s Ikea items he has kept from his early days working at the store, are now back in fashion, thanks to the recent popularity of Scandi-chic.

"People used to think it was really naff, but now it's back in vogue," he laughs.

It seems trying to cram flat-pack furniture into your car, missing screws, and the ensuing marital tensions, haven't been enough to put people off. Ikea has a 12% market share in the UK, outstripping rivals such as Argos, John Lewis and sofa retailer DFS.

Ikea

IkeaPatrick O'Brien, UK retail research director at retail consultancy GlobalData, says the chain's success has been driven by the fact that it offered a completely new concept.

Ikea's style was in sharp contrast to the "chintz and dowdy" mish-mash dominating UK homes three decades ago, he says.

But it wasn't just what Ikea was selling that was different, but how it was selling it, he says.

"You come here, you walk through this maze this way round, then you pick it up in the warehouse. It was a really prescriptive way of doing stuff," he says.

In a world where the concept of "customer as king" still ruled, dictating a customer's journey in this way had never been done before Mr O'Brien says.

It's this very journey of course that frustrates many of its customers.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBut the baffling warren of mocked-up rooms - you're wholly dependent on floor arrows, there's no glimpse of the outside world to help you orient yourself - is far from accidental.

Dr Dimitrios Tsivrikos, a consumer and business psychologist at University College London says the key to Ikea's strategy is suggesting to the customer that they are in charge: they give you your own pencil, paper and trolley, there's only a smattering of staff, and there's no hard-sell from sales assistants.

But in fact you're on what he calls "a forced journey".

As you involuntarily wend your way through bedrooms and kitchens, on your way to office furniture, you inevitably end up picking up things you never intended to buy.

Ikea

IkeaThe other factor that has helped to drive the chain's success is its "layered pricing" with some items incredibly cheap and others more expensive, he says.

Customers' assumption that everything is a bargain, means that they often add more expensive items to their trolley too.

Travelling to the out-of-town store plus the long queues are also ironically part of Ikea's winning strategy. The experience is so draining we tend to buy more to avoid having to return in the near future.

IKEA

IKEAThe chain is beginning to respond to some of customers' most common frustrations.

You can now order some bulkier items online for home delivery. And it recently bought US start-up firm TaskRabbit, which helps you hire people to do odd jobs including flat-pack furniture assembly.

It has also started experimenting with selling its furniture through other online retailers as part of a wider push to become more accessible to shoppers.

And running directly counter to its original out-of-town model, the company is also testing a smaller, city centre store format as well as order and pick-up points in town centres.

Ikea's sheer size makes more radical change difficult, says Mr O'Brien. He says its challenge is to convince customers it offers quality whilst maintaining its reputation for low prices.

"People's exposure to Ikea is usually at student age where they tend to buy the cheapest thing and then as they get jobs and have a bit more money, they tend to move on to more expensive retailers," he says.

So could we all tire of Ikea eventually and begin to go elsewhere?

Mr O'Brien thinks not.

As long as we still want to sit on a sofa, or lie on a mattress before we buy, shops like Ikea will be relatively immune from competition from purely online rivals.

Plus of course, there are always some people who inexplicably still relish the Ikea experience: usually those who are really keen on Swedish meatballs.