The seaside towns hit by a rising tide of debt

BBC

BBCSeaside towns in England and Wales - and the young families living in them - are suffering the worst levels of debt in the country, new figures reveal.

The Isle of Wight has the highest level of insolvencies amongst young adults, according to the Insolvency Service, followed by Torbay and Scarborough.

Overall the number of 18 to 34 year-olds becoming insolvent rose by 31.3% between 2015 and 2016.

It comes ahead of a possible rise in interest rates as soon as next month.

Any increase would be the first in the UK for over ten years - and would inevitably make borrowing more expensive.

Coastal communities tend to be the worst affected because much of the work is low-paid and seasonal.

'I didn't want to exist'

Daniel and his wife Laura - who live on the Isle of Wight - have joint debts of around £30,000.

He works full time in construction, while she looks after their two-year old son. They're both 28 years old.

Unable to pay for food, they built up debts of £7,000 on a credit card. They also owed £3,000 in council tax.

"At one point, to survive, we had chickens. We were living off eggs. Just eggs, bread and milk, because that's all we could afford," says Daniel.

But things got even more serious than that.

"I couldn't have been in a worse place," says Laura. " I had depression and anxiety, and I was pregnant. At times I even felt suicidal.

"And that's the worst thing, because I look back and think If I'd ever gone through with that then my son wouldn't be here. I didn't want to exist."

Daniel is in the process of declaring himself bankrupt, while Laura has applied for a Debt Relief Order (DRO), a separate form of insolvency.

'No money coming in'

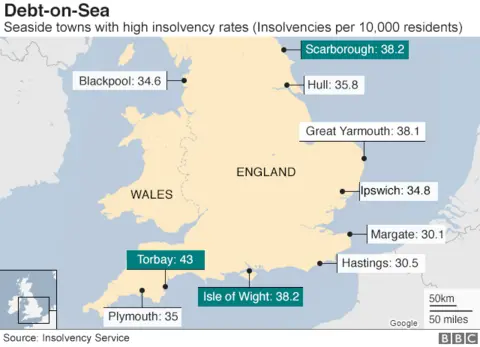

Torbay in Devon has the highest overall rate of insolvencies in England and Wales, with 43 per 10,000 residents in 2016. Stoke on Trent has the second highest rate, with the Isle of Wight and Scarborough in joint third.

Great Yarmouth and Ipswich also have high insolvency rates.

Sandra Snell, who works as a debt counsellor for Christians Against Poverty on the Isle of Wight, believes there are particular pressures on seaside communities.

Unemployment is high, and much of the work is seasonal.

"In the season there'll be more work because of the tourist trade," she says.

"Some people will slot into jobs, whether it's cleaning the chalets or waiting on tables; then when the season comes to an end, they're back to square one, and they've got no work."

When people transfer onto benefits in the winter months, there can be delays before their money comes through.

"People are waiting at least 12 weeks. There's no money coming in and they're expected to live on nothing."

The cost of living can also be much higher than elsewhere. Petrol is on sale on the Isle of Wight for up to 130 pence a litre - around 10% higher than the national average.

Insolvencies rising

A survey for the accountancy firm PwC suggests that 28% of those in the 25 to 34 year-old age group are worried about making repayments on their debt.

And 20% of young adults have used credit cards to pay for essential items like food.

Official figures show that insolvency rates are now rising for the first time since 2009. However they are a long way from the peak of insolvencies, seen in 2009.

Similarly, the total amount of consumer credit - the measure of borrowing used by the Bank of England - may have reached £203bn in August, but that is lower than in 2008.

Consumer credit is currently growing at 9.8% a year - down from a 10.9% peak last November, and way below the 15.8% growth seen in September 2002.

Meanwhile Daniel and Laura say the debt help they received from CAP has transformed their outlook.

"They possibly saved my life," says Laura.

"My wife wouldn't be here without them," adds Daniel.