How many people will the cap on energy prices help?

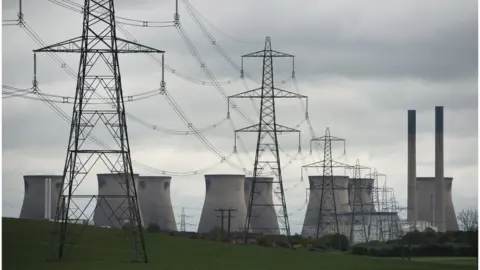

Getty Images

Getty ImagesYou'll have seen the stat. Two-thirds of UK households on rip-off energy tariffs, or words to that effect.

And it is a figure still being used. On Wednesday, the government said this of its planned cap on energy price:

"This would protect around two-thirds of households."

Except that doesn't appear to be right.

Market breakdown

According to regulator Ofgem's latest figures - which the government says it's using - about 15 million households are on standard variable tariffs, which on average are about £300 a year more expensive than the cheapest offers available.

That is out of 27 million UK households, or about 55% of the total.

In fairness, that is still a big chunk of the market. And two years ago 17 million UK households were on standard variable tariffs - a lot closer to the government's two-thirds figure.

But this still overstates the number of people who stand to benefit from the government's plans to instruct Ofgem to cap these SVTs, which households roll onto when a fixed offer comes to an end.

About three million of these households who use prepayment meters are already protected by a price cap introduced by the regulator in April this year.

That was the first step in a widely-welcomed push to protect "vulnerable" households - those who, for whatever reason, find it harder to switch to the cheaper tariffs offered by more than 50 upstart energy providers.

This leaves 12 million, or about 44% of UK households, paying those high SVT rates.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAlready protected

Except Ofgem this week proposed extending its price cap protection to about one million households receiving the Warm Home Discount from February.

And it said it was working on offering that protection to a further two million households from next winter.

Now the government has conceded its market-wide cap on standard variable tariffs won't be in force until next winter. It has passed the tricky task of designing and setting the cap to Ofgem.

So by the time it comes into force, about nine million households - or one-third of the market - could be on the higher standard variable tariffs without any type of price protection already in place.

That doesn't take account of another year in which households paying over the odds can switch to one of the cheaper tariffs on offer.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThree years

Remember, the part of the market that the government is really trying to help is the households who have been on a standard variable tariff for more than three years.

Those are the people that, for whatever reason, seem to be stuck paying over the odds. And Ofgem's data show that low-income households, those living in rented social housing, those aged 65 or older or those with a disability are more likely not to have switched supplier in the last three years.

Unfortunately, it is hard to break the market down much further. Ofgem's latest data from April looks at customer accounts rather than households (and where a household has a separate supplier for gas and electricity that can mean double counting).

But those figures suggest that of all non-prepayment accounts on SVTs, about 55-60% had been in that position for more than three years.

If the regulator has got it right, those accounts should be those that benefit from the proposals announced this week. Which implies - albeit very roughly - that the remaining slice of the market who have been stuck on SVT long-term but won't be protected by next winter should be reasonably small.

And this is where designing an effective price cap gets tricky.

Ofgem must try to reduce energy costs meaningfully for that subsection of the market that is stuck on pricey tariffs and won't already have been helped by already announced measures.

But it has been instructed to do so in a way that doesn't reduce the incentive for the rest of the market to shop around for the best deal.