The great crash - 10 years on

Reuters

ReutersOn 9 August 2007 the French investment bank BNP Paribas announced it was shutting down three investment funds - meaning people who had invested in them couldn't get their money out.

Its press release read as follows:

"The complete evaporation of liquidity in certain market segments of the US securitization market has made it impossible to value certain assets fairly, regardless of their quality or credit rating."

In English what that means is "we couldn't sell this stuff if we tried because no-one knows what it's worth, if anything".

It is seen by most as the beginning of the worst financial crisis since the 1930s. The stuff they couldn't value was bundles of US mortgages.

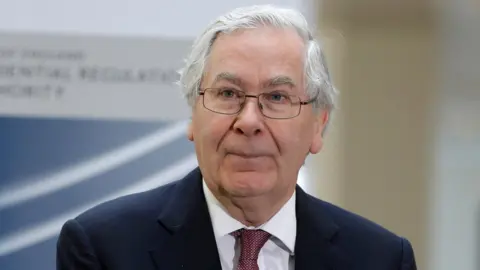

On the front line was Mervyn, now Lord, King - governor of the Bank of England at the time. He told the BBC that it wasn't so much the announcement that rattled him but the sudden and dramatic response from the European Central Bank.

"What they did was to lend, for one day, 100bn euros (£90bn) to the financial system. That's rather a lot of money and what that did was to make people wonder what it was they knew that others didn't - we wondered that too.

"That was the first day of my holiday. It was also the last day of my holiday. In fact the last holiday for four years."

A weak link

That first tremor developed into a full-blown financial earthquake that shook the mightiest institutions around the globe, destroying many in the process, including Northern Rock and US investment bank Lehman Brothers.

It proved beyond the powers of central banks alone to save the financial system, with governments forced to nationalise some lenders and provide tens of billions of taxpayers' money to prop up banks like RBS that otherwise would have collapsed.

Lord King says a banking system we thought of as safe turned out to be the weak link in the global economy.

He recalled a meeting with the Financial Services Authority (FSA) when he and the then-Chancellor Alistair Darling were told that "Jaguar is in trouble".

They expressed their bafflement at why a carmaker should be in trouble until realising that the financial regulator was using a codeword for yet another bank on the brink of collapse.

"In these private meetings code-names were used in a way that seemed to us completely pointless".

Surprisingly perhaps, he said those days were not filled with stress and anxiety.

"We spent 20 hours a day on this for many years. So it wasn't nail-biting, it was more of a long slog trying to do the right thing."

The China effect

Lord King insists that the financial crisis was not, in itself, the cause of the economic meltdown - but a symptom of growing global economic imbalances.

The introduction of China into the world economy had the effect of pushing down prices and pushing down wages, which pushed down interest rates.

That lead to a huge increase in demand for loans, which saw banks ramp up their lending.

"The reason the banking system got into trouble was that as they expanded, they did so with borrowed money rather than raising new capital."

He says these forces of globalisation meant there had been many losers and those who lost out were not dealt with honestly.

"We've allowed them to lose and then after the event said 'well that's just tough, the country as a whole is better off. You better retrain or reskill yourself'."

That dissatisfaction has been felt in the votes for Donald Trump and the vote to leave the EU.

"In both those cases we saw people voting against something," says Lord King.

Hard Brexit

He describes the coverage of the Brexit debate both before the vote and since as "hysterical".

When asked his own view of the economic impact of leaving the EU, he says: "I don't know - that's the only honest answer."

One thing he is sure about is that as the UK approaches the Brexit negotiations, we must be prepared to walk away otherwise our position lacks credibility.

By walking away he means falling back on a trade relationship governed by the rules of the World Trade Organisation.

"If you are going to have any success in this negotiation you need to have a fall back position that the other side understands and thinks is credible.

"It is not first choice but we have to have an option otherwise the other side won't listen. This ought to be something people can agree on irrespective of whether they voted for Brexit or not."

Ten years on from the crisis he is unwilling (perhaps conveniently) to apportion responsibility for what happened.

"I don't think it helps to start trying to blame people - otherwise you get into a situation where you think that punishing the people you blame will protect you from the next crisis which of course it won't."

He does, however, think valuable lessons were learnt and the financial system is a lot safer now than it was 10 years ago.

"We have a procedure for dealing with a failing bank which we didn't back then."

So did he enjoy his time on the front line of the crisis?

"I don't think enjoyed is the right word," says Lord King. "But when you do an interesting job you want to live through interesting times and we certainly did that."