Inside a US/UK trade deal

NHS

NHSRelations with the United States were always going to be a high priority for British trade policy post-Brexit.

So no surprise that Liam Fox has gone to Washington to discuss prospects.

The International Trade Secretary is pushing for a bilateral trade liberalisation agreement with the US to take effect when the UK leaves the EU.

And his American hosts seem well disposed to the idea in principle. Better access to the US market would go down well among many UK businesses too.

It is, after all the UK's largest single export market, though well behind the rest of the EU taken together.

The US is also the second largest foreign supplier to the UK. So a freer trade relationship could reduce the cost of those imports.

Priority

There was also a great deal of enthusiasm among British business for the EU's negotiations with the US, a project known as the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP).

Now that British business won't be able to make use of any benefits that might come from that exercise, if it is ever completed, a deal with the US would be helpful for many.

Having said that, many regard it as a higher priority to preserve trade access to the EU as far as possible on existing terms. That is broadly the position of a number of British business lobbies.

There are some areas of any UK/US talks that might be difficult. Experience with the TTIP negotiations gives some clues as to the kind pressures the British government is likely to face at home.

Science Photo Library

Science Photo LibraryOne is resolving disputes under the agreement, particularly any involving foreign investors.

Many trade and investment agreements provide for tribunals to be established if a foreign investor believes their interests have been harmed by the host government acting in a way that contravenes the agreement.

They can seek financial compensation, and there are many cases where they have been successful. The system is known as investor state dispute settlement (ISDS).

It has been around for decades, but has become more controversial in recent years. Critics see it as giving international businesses unfair leverage over the policies of elected governments.

NHS impact

There will be business lobbies on both sides keen to see some sort of arrangement along these lines and campaigners vigorously opposed.

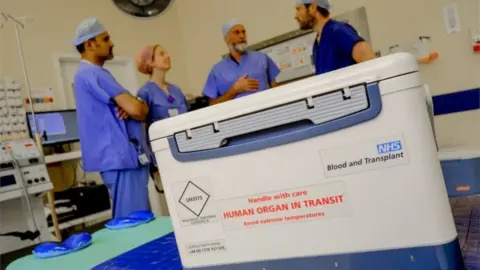

There is a particular issue for some groups in the UK about how this might affect the National Health Service. It came up in the context of the TTIP negotiations.

The issue was partly whether the agreement might force the British government to privatise health service provision - and also about whether the agreement would make it hard or impossible to reverse any privatisation that did occur.

The issue was that reversing such a move could deprive a foreign health company of business, which campaigners argued could enable it to use the ISDS tribunal system to seek compensation from the host (British) government.

Reuters

ReutersThe US has some big healthcare businesses which would be keen to establish a stronger presence in the UK. How well founded that fear would be would depend on the wording of the agreement, but once detailed negotiations get underway it's likely to be brought up.

Chlorine and hormones

In the context of TTIP, the idea that it would compromise public provision of healthcare was robustly rejected by, among others the British government, but campaigners did not accept that.

Then there are food issues. Dr Fox has already responded to concerns about American chicken washed with chlorine. That came up in the TTIP talks too and it might well make an appearance again. The practice is widely used in the US to remove microbial contamination, but it is not permitted in the UK.

Beef fed with growth promoting hormones, another practice used in the US, could also be difficult. It's banned in the EU on the basis of health concerns.

This is a trade dispute that has rumbled on for many years and the EU has lost the case in the World Trade Organization, which accepted that the hormones were safe.

The EU has never complied with that ruling and still bans such meat.

Genetically modified approvals

Another food issue is genetically modified crops. They do have a presence in the European food chain, partly through animal feed. But the approval process for new GM crops is seen by US farm groups as excessively slow and cumbersome.

Movement on all three of these issues is likely to be important for US negotiators. The National Farmers' Union in the UK is receptive to the idea of reforming the GM approvals process, but the other two are more of a problem.

Nonetheless there are certainly opportunities that businesses in both countries can see. For industry, the relatively straightforward area is tariffs, taxes on imported goods.

They are relatively low in both the US and the UK (which currently adopts the EU's tariff policy). But there are some goods for which they are relatively high (10% for cars entering the UK from outside the EU, for example).

Many industry and financial services groups would also welcome closer regulatory cooperation. It would simplify business for suppliers and could conceivably lower costs for customers.

In any event, for now the UK remains a member of the EU and its common trade policy.

But that certainly doesn't stop negotiators discussing what a post-Brexit deal would look like.