Why didn't electricity immediately change manufacturing?

Alamy

AlamyFor investors in Boo.com, WebVan and eToys, the bursting of the dotcom bubble came as a bit of a shock.

Companies like this raised vast sums on the promise that the worldwide web would change everything. Then, in the spring of 2000, stock markets collapsed.

Some economists had long been sceptical about the promise of computers. In 1987, we didn't have the web, but spreadsheets and databases were appearing in every workplace - and having, it seemed, no impact whatsoever.

Boo.com

Boo.comThe leading thinker on economic growth, Robert Solow, famously quipped: "You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics."

It's not easy to track the overall economic impact of innovation but the best measure we have is something called "total factor productivity".

When it's growing, that means the economy is somehow squeezing more output out of inputs, such as machinery, human labour and education.

The productivity paradox

In the 1980s, when Robert Solow was writing, it was growing at the slowest rate for decades - slower even than during the Great Depression. Technology seemed to be booming but productivity was almost stagnant.

Economists called it the "productivity paradox".

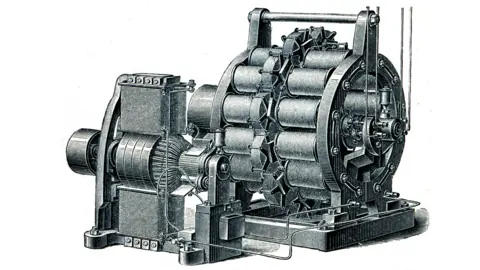

For a hint about what was going on, rewind 100 years. Another remarkable new technology was proving disappointing: electricity.

Some corporations were investing in electric dynamos and motors and installing them in the workplace. Yet the expected surge in productivity did not come.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations which have helped create the economic world in which we live.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

The potential for electricity seemed clear.

Thomas Edison and Joseph Swan independently invented usable light bulbs in the late 1870s.

In 1881, Edison built electricity generating stations at Pearl Street in Manhattan and Holborn in London.

Alamy

AlamyWithin a year, he was selling electricity as a commodity. A year later, the first electric motors were driving manufacturing machinery.

Yet by 1900, less than 5% of mechanical drive power in American factories was coming from electric motors. The age of steam lingered.

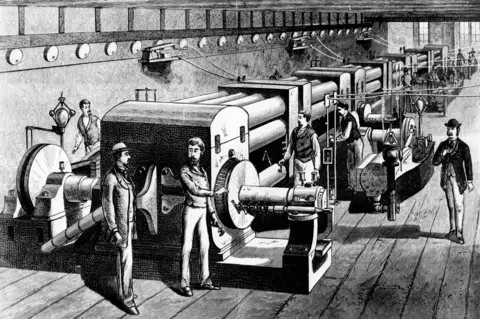

A steam-powered factory must have been awe-inspiring.

The mechanical power came from a single massive steam engine, which turned a central steel drive shaft that ran along the length of the factory. Sometimes it would run outside and into a second building.

Alamy

AlamySubsidiary shafts, connected via belts and gears, drove hammers, punches, presses and looms. The belts could even transfer power vertically through a hole in the ceiling to a second or even third floor.

Expensive "belt towers" enclosed them to prevent fires from spreading through the gaps. Everything was continually lubricated by thousands of drip oilers.

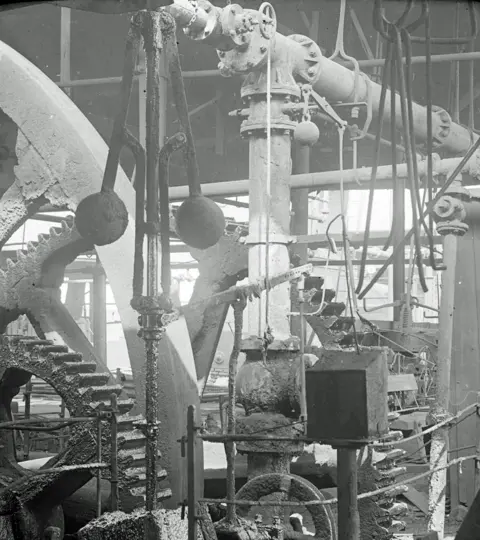

Steam engines rarely stopped. If a single machine in the factory needed to run, the coal fires needed to be fed.

Alamy

AlamyThe cogs whirred, the shafts span and the belts churned up the grease and the dust, and there was always the risk that a worker might snag a sleeve or bootlace and be dragged into the relentless, all-embracing machine.

Some factory owners did replace steam engines with electric motors, drawing clean and modern power from a nearby generating station.

Revolutionary impact

But given the huge investment this involved, they were often disappointed with the savings. Until about 1910, plenty of entrepreneurs looked at the new electrical drive system and opted for good old-fashioned steam.

Why? Because to take advantage of electricity, factory owners had to think in a very different way. They could, of course, use an electric motor in the same way as they used steam engines. It would slot right into their old systems.

But electric motors could do much more. Electricity allowed power to be delivered exactly where and when it was needed.

Small steam engines were hopelessly inefficient but small electric motors worked just fine. So a factory could contain several smaller motors, each driving a small drive shaft.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAs the technology developed, every workbench could have its own machine tool with its own little electric motor.

Power wasn't transmitted through a single, massive spinning drive shaft but through wires.

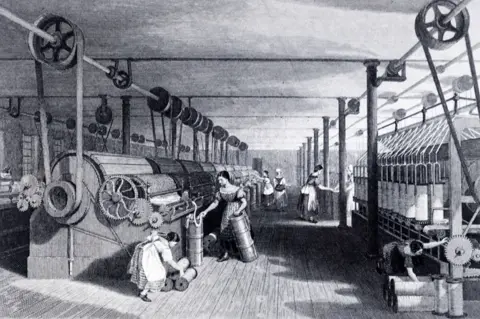

A factory powered by steam needed to be sturdy enough to carry huge steel drive shafts. One powered by electricity could be light and airy.

Steam-powered factories had to be arranged on the logic of the driveshaft. Electricity meant you could organise factories on the logic of a production line.

More efficient

Old factories were dark and dense, packed around the shafts. New factories could spread out, with wings and windows allowing natural light and air.

In the old factories, the steam engine set the pace. In the new factories, workers could do so.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFactories could be cleaner and safer - and more efficient, because machines needed to run only when they were being used.

But you couldn't get these results simply by ripping out the steam engine and replacing it with an electric motor. You needed to change everything: the architecture and the production process.

And because workers had more autonomy and flexibility, you even had to change the way they were recruited, trained and paid.

Factory owners hesitated, for understandable reasons.

Of course they didn't want to scrap their existing capital. But maybe, too, they simply struggled to think through the implications of a world where everything needed to adapt to the new technology.

In the end, change happened. It was unavoidable.

Mains electricity became cheaper and more reliable. American workers become more expensive thanks to a series of new laws that limited immigration from a war-torn Europe.

Leap forward

Average wages soared and hiring staff became more about quality and less about quantity.

Trained workers could use the autonomy that electricity gave them. And as more factory owners figured out how to make the most of electric motors, new ideas about manufacturing spread.

Come the 1920s, productivity in American manufacturing soared in a way never seen before or since.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesYou would think that kind of leap forward must be explained by a new technology. But no.

The economic historian Paul David gives much of the credit to the fact that manufacturers had finally figured out how to use technology that was nearly 50 years old.

Which puts Robert Solow's quip in a new light.

More from Tim Harford:

By 2000 - about 50 years after the first computer program - productivity was picking up a bit.

Two economists, Eric Brynjolfsson and Lorin Hitt, published research showing that many companies had invested in computers for little or no reward while others had reaped big benefits.

Time and imagination

What explained the difference was whether the companies had been willing to reorganise to take advantage of what computers had to offer.

That often meant decentralising, outsourcing, streamlining supply chains and offering more choice to customers.

You couldn't just take your old systems and add better computers. You needed to do things differently.

Amazon

AmazonThe web is younger still. It was barely a decade old when the dotcom bubble burst.

When the electric dynamo was as old as the web is now, factory owners were still attached to steam. The really big changes were only just appearing on the horizon.

The thing about a revolutionary technology is that it changes everything - that's why we call it revolutionary. And changing everything takes time and imagination and courage - and sometimes just a lot of hard work.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.