Defecting online: How Myanmar’s soldiers are deserting the army

Facebook

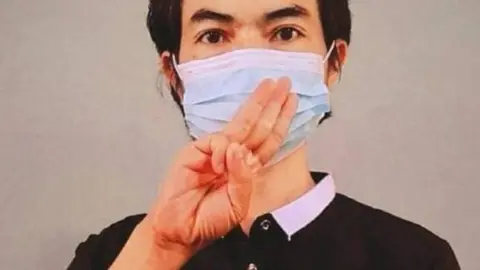

FacebookMyanmar is engulfed by an increasingly deadly civil war, which began when the Tatmadaw - the country's armed forces - seized power last year. Now, helped by an underground network armed with Facebook and Telegram accounts, soldiers are leaving in droves.

Agne Lay - not his real name - sits by his phone, waiting patiently.

Five minutes later, he receives a message.

A soldier desperately needs his help. He wants to leave the Tatmadaw, but he fears being caught. Can Mr Lay help?

Messages like this come in every day, not just to 44-year-old Mr Lay, but also to hundreds who volunteer with People's Embrace, a network helping disillusioned soldiers and police officers defect.

"We advertise on Facebook that those who want to leave should contact us on Telegram," Mr Lay tells me, outlining the operation via an online link from an undisclosed location inside Myanmar (also called Burma).

With the Tatmadaw out to infiltrate their network, he's wary of divulging many specifics about how they operate. But I've spoken to several ex-Tatmadaw soldiers who have broadly described how the operation works.

Their activities come with massive risks. Mr Lay says he knows exactly what would happen if he were to be captured by his former comrades.

"I would be executed," he says.

Bloody conflict

Getty Images

Getty ImagesMyanmar's civil war has turned increasingly violent after last year's overthrow of the civilian government.

On 1 February 2021, following Aung San Suu Kyi's re-election, the Tatmadaw overthrew the National League for Democracy (NLD) government. Military leaders justified the coup by claiming voter fraud, although the country's electoral commission found there was no evidence to support such claims.

Civilians took to the streets - but their protests were met with violent suppression by the military.

At the time, Mr Lay was a sergeant working an office job. Confused by the chaos erupting around him, he turned to social media to find answers. He says he discovered videos showing soldiers carrying out extrajudicial killings.

"I witnessed people being deliberately targeted, shot in the head, and killed," he says. "There were no accidental deaths."

His horror intensified when the Tatmadaw forced his teenage son to join the military reserves - something he couldn't prevent from happening.

"I was told that if I did, I would be punished," Mr Lay says.

It was the final straw.

"I was no longer willing to stay in the force," he says.

Five months after the coup, Mr Lay gathered his family and drove into the mountains. They were among the first to be assisted by People's Embrace.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWeaponising the web

Mr Lay is now a part of the organisation to which he once turned. He works remotely from a "liberated area" - one of the regions controlled by rebels, where minority ethnic groups are concentrated and the civilian National Unity Government (NUG) holds sway.

He described to me how Facebook and Telegram were central to both his awakening from what he calls "years-long brainwashing" and his escape.

People's Embrace has more than 100,000 Facebook followers. Would-be defectors who make contact online are vetted, and those who are successfully extracted are provided with food, shelter, security and a stipend.

"If friends [of defectors] want to leave the military, they pass the link to each other," he says.

The key role that social media plays in the defector pipeline is just the latest twist in the unusual and often troubling use of technology in the modern history of Myanmar.

A decade ago very few people had access to a mobile phone, let alone the internet.

But as costs declined, social media spread quickly. Now, more than half of Myanmar's population use Facebook.

It's allowed movements like People's Embrace to grow - and has also spread word of alleged atrocities by the Tatmadaw.

"When other avenues for promoting accountability and seeking justice are unavailable, [civilians] can reach out online," says Daniel Anlezark, deputy head of investigations at the London-based Myanmar Witness NGO.

His team has verified thousands of videos online showing soldiers acting violently and with impunity.

But Facebook was also instrumental in spreading disinformation and hate. This led to the genocide of Rohingya Muslims, according to a UN report which said top military figures in Myanmar must be investigated for genocide in Rakhine state and crimes against humanity elsewhere. At the time, the government of Myanmar rejected those allegations.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIt's why James Rodeheaver, from the UN's Human Rights Council, describes social media as a "double-edged sword" in the country.

He notes that the Tatmadaw has been able to spread misinformation, and that the military uses internet blackouts as an act of warfare - shutting off communications before launching attacks, and thus turning people's reliance on online connection into a weakness.

A new dawn

The BBC contacted the Tatmadaw and put to them the allegations made by Mr Lay and others, but we did not receive a reply.

As the conflict grinds on, People's Embrace and the NUG are attracting more and more supporters.

We can't independently verify the numbers, but the NUG says that more than 8,000 soldiers and police officers have defected. Some go right back into battle for the opposition, or work as police officers, while others bolster the People's Embrace recruitment effort and some simply choose to lead civilian lives.

Having helped many of them defect, Mr Lay feels like his life has regained purpose.

"Basic human rights are being lost," he says. "Our living standards are at an all-time low and there's corruption. If you see all this, you will feel sorry for us."

He says he's determined to keep on fighting until the coup is reversed - and the Tatmadaw is overthrown.

Listen to Defecting online: How soldiers are deserting the Burmese army from Trending on the BBC World Service.