China's fledgling hip-hop culture faces official crackdown

iQiyi

iQiyiLast summer, a reality show called The Rap of China took the country by storm.

The show brought hip-hop music from the underground into the limelight and made it a multi-million dollar business. Several of the top contestants shot to stardom.

In the past few weeks, however, things took a surprising turn and the buzzing hip-hop scene was quickly muzzled.

It all started with PG One, one of the two rappers who won The Rap of China. He was accused of having an affair with a married celebrity.

The accusation, which was never substantiated, snowballed into a case not only against PG One, but against hip-hop music in general.

'Vulgar and low taste'

State media led the crusade against PG One, calling his lyrics sexist and decadent. The influential Communist Youth League criticised one of his old songs, Christmas Eve, for promoting drug use with lyrics about "white powder walking on the board".

China Women's News accused PG One of misogyny over his use of obscene language to describe women.

The incident also seems to have triggered a crackdown on the entire music genre.

A memo surfaced last week after a meeting of the state authority which oversees press and television and has almost total control over what can appear on air. The memo said programmes could no longer feature any hip-hop content or artists.

All programmes shall adhere to the "four notes" when it comes to inviting on-air guests, the memo says. "Do not use celebrities with low moral values; do not use those who are vulgar and of low taste; do not use those whose thoughts and style are not refined; and do not use those who are involved in scandals."

As the memo circulated online, the other winner of The Rap of China, GAI, suddenly left the reality show he was appearing in, which was called I Am a Singer.

A few leaked screen grabs of chats with GAI's management team seem to suggest that he quit because of "pressure from above".

GAI's agent, Zhang Xiaotao, told the BBC that the team had no response as to why GAI quit, but that he had never heard of any hip-hop ban.

Another TV show, Happy Camp, suddenly removed VAVA - the most popular female rapper who rose to fame from The Rap of China - from their latest episode.

No-one knows exactly why she was removed but in what seems like a quick-fix solution, Happy Camp republished their promotional video after erasing VAVA. She was awkwardly cropped out of all their shots.

'It's what hip-hop is'

As the state issues more stringent rules on what the public can and cannot see, many rappers, including GAI who used to be a "gangsta" style rapper, have changed their approach to participate in mainstream state TV programmes.

They have, in interviews, spoken about the "positive energy" of music and socialist "core values" that the Chinese authorities promote.

For many hip-hop fans in China, this sort of government reaction to the rapid popularity of the genre was an inevitable consequence of cosying up to the authorities.

"I knew this would happen sooner or later. Hip-hop culture does not fit into the socialism 'core values'," one social media user wrote.

Another said that lyrics about white powder, money, girls, sex and violence were "what hip-hop is".

"It's for people who love it. Criticising its 'dark spots' is like criticising peppers for being spicy," they said.

Reuters

ReutersFaced with immense pressure, rapper PG One took all of his songs offline and blamed his lyrics on influence from the "black music".

"I will add more positive energy in my music works and serve as a better model for my fans", says PG One on his official Weibo account.

Many other rappers, however, did not agree with how PG One linked his demise to the influence of "black music" and have accused him of racism and insincerity.

So is this the end of the rap music explosion in China?

MC Webber, one of China's most respected underground rapper, does not think so.

He says the mainstream current hip-hop scene was not real hip-hop anyway. He calls what's come out of The Rap of China "Xi Ha", a term that's translated from "hip-hop" but was mostly used in Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Al Rocco, a rapper based in Shanghai who also participated in The Rap of China, says he is not worried about the future of hip-hop.

"The government, they don't understand the culture yet, so they are scared," he told the BBC. "We have a different system here and it's just evolving now.

He told the BBC that one of his recent shows in Chongqing got unexpectedly cancelled following the hip-hop ban.

"They've always asked to check my lyrics, but I feel like it's much tighter now," says Al Rocco.

Of course censorship and official disapproval is nothing new to the hip-hop scene. In the US, where rap music originated, there was a public and official backlash in the late 1980s against what some considered to be a violent and obscene culture portrayed in hip-hop.

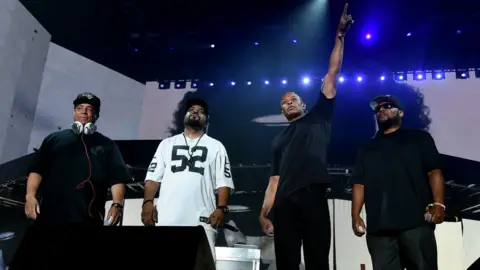

Getty Images

Getty ImagesNWA, for example, received letters from the FBI accusing them of promoting violence against the police for their famous and famously explicit anthem against police brutality and racial profiling.

But the reaction against them also helped throw the subculture into mainstream.

While there's far less scope for Chinese hip-hop artists to flourish in the face of government restrictions, rappers from the original underground scene say they're not going anywhere.

One underground rapper, who runs his show business, told the BBC anonymously that it was a shame the whole industry had to bear the consequence of one man's mistake.

But he insisted "the sky hasn't collapsed" on rap entirely and it would continue to evolve.

Before The Rap of China, he says, "we were just as happy, only with less money".