Can touchless tech create 'equitable' gaming?

BBC

BBCFor many people, grabbing a mouse or games controller to operate their computer is second nature.

However, for some disabled people, it can be a challenge, or even impossible.

There are alternative input methods such as eye-tracking - but they often require specialised equipment.

And while gaming giants such as Sony have designed accessible controllers for their own consoles, they don't work for everyone.

Which is where software like MotionInput - and the concept of "touchless computing" - come in.

The aim: to allow anyone to play any game, using only standard laptop equipment.

Rather than requiring users to be able to operate a mouse or keyboard, MotionInput lets them create whatever new inputs for clicks or controls work best for them.

Users can choose whatever facial expressions or physical gestures suit them and their needs, inputted via their computer's webcam.

So, for example, pulling a fish face could represent a right click, or raising your eyebrows could be a double click.

The software which supports it is available for free on the Microsoft Store.

Professor Dean Mohamedally, professor of computer science at University College London, has led development of MotionInput over the last four years with the help of more than 200 students.

He said it "democratises" previous technologies, enabling children to play games using their own body movements, in an example of "equitable computing".

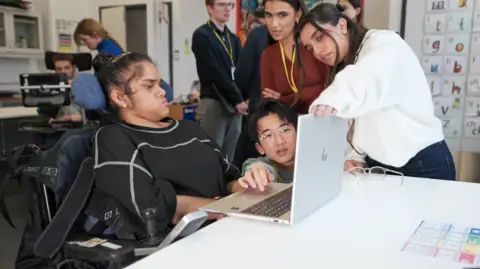

"It is easy," says Safiya, one of several pupils at the Richard Cloudesley School in London. The school has been helping UCL students spot potential bugs or issues in the software.

"It helps me experience every action of the game", Safiya added.

A fan of games on the now discontinued Nintendo Wii, such as tennis and boxing, she had only previously tried Nintendo's own hardware.

"This new controller helps me play better," she said.

I got to try MotionInput for myself – mainly on popular games Minecraft and Rocket League, but also on more complex titles such as Doom and Forza Motorsport.

It took practice and perseverance to master the intricacies of some of the control methods.

And I can now say I played Minecraft with my eyes, even if I could not quite avoid crashing into the odd virtual cow.

But I was trying multiple different inputs in a short space of time, whereas in reality people are likely to focus on one or two that are easiest for them to use, so my experience probably was not typical.

What makes this personalised tech possible is artificial intelligence (AI) software provided by Intel. It uses machine learning to recognise a user's body parts and how their motions or expressions correlate to certain actions during gameplay.

This sort of assistive technology has huge power to transform lives, and with so much of modern life happening around our devices, enabling more people to access them easily has clear benefits.

Dr Lynsay Shepherd, senior lecturer in cybersecurity and human-computer interaction at Abertay University, agrees.

"In the context of gaming, it’s important that computers and consoles are accessible for individuals, something that has become particularly evident in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic," she says.

"Games can reduce feelings of social isolation and support positive mental health, and people with accessibility issues deserve opportunities to engage in gaming."

She notes similar efforts led by charities such as SpecialEffect and Able Gamers, who work with developers to create custom controllers, are also helping disabled gamers have better experiences.

But she said accessible technologies had to remain easy to use and affordable if they were to be adopted more widely.

"The games industry can support development of these technologies by creating a pipeline to help gamers with accessibility issues become involved in testing, and by hiring gamers with disabilities as accessibility consultants," she said.

At the moment the focus is on gaming, but tech such as MotionInput has potential that reaches far beyond just entertainment.

It is believed touchless computing could be beneficial in healthcare, construction and education.

"Given our increasingly digitised society, these [technologies] can support people in maintaining social ties and provide assistance in the work environment," Dr Shepherd added.

The future aim of UCL's MotionInput software is to commercialise its non-accessibility applications.

But for now, it’s all about the games.

Additional reporting by Liv McMahon