The police job that is beyond the stuff of nightmares

BBC

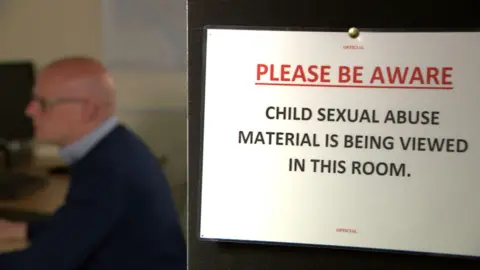

BBCDavid Murray's office has a warning on its door: "Please be aware: child sexual abuse material being viewed in this room."

The detective constable spends hours examining pictures and watching videos, the worst of which are beyond the stuff of nightmares.

He puts himself through it because he knows the job is important.

The father of two young boys admits it takes its toll, yet he wishes he had started the job far earlier in his policing career.

He says it's worth it, because every week he and his colleagues are identifying young victims, and protecting them from further abuse.

Earlier this week, Police Scotland invited BBC Scotland News to witness its work demonstrating the change in offending behaviour since the Covid pandemic, revealing that paedophiles were making direct contact with children online within 30 seconds of trying.

'On our doorstep'

David was the first victim identification officer to work with Police Scotland's national child abuse investigation unit.

After four years, he now has three colleagues and an ever increasing workload.

The unit is conducting 700 inquiries a year and executing 15 to 20 search warrants every week, seizing dozens of devices from the homes of suspects.

The job of the victim identification officers is to examine images and footage found on these phones and laptops, to try to find children who've been abused.

According to Interpol, online child sexual abuse is one of the rare crime areas where police officers start with the evidence and work their way back to the crime scene.

Once images are found, the victim identification specialists take over, combing through the images with the objective of removing the child from harm and arresting the abuser.

But their workload is increasing as fast as they can get through them.

David says: "Four years ago we were identifying approximately 25 to 30 victims a year. We're doing more than ten times that now."

Shockingly, the victims are close to home.

"Last year we identified nearly 400 victims and 90% of those children are from Scotland.

"When I started, I thought it was a problem that was far away, but it's on our doorstep. It's children in our community."

Horrifying contrast

The contents of the devices are uploaded to the UK-wide child abuse image database.

If they've been discovered before, they don't have to be viewed again, but if they're new, they're classed as "first generation" images and checked by David and his colleagues.

The grim reality of that is that much of the abuse takes place within households where the perpetrator knows the victim.

That means devices can include pictures of normal family life, providing a horrifying contrast to the images of abuse and vital information for the detectives.

"Essentially we start looking for clues in the pictures as to where this footage was taken, things like plug sockets or bits of clothing, maybe school uniforms and football strips, anything that would perhaps indicate where the child lives," says David.

"A lot of our identifications are made from non-indecent images."

One victim was recently traced in Glasgow after a detective recognised a water tower in the background of a selfie.

Steps are taken to safeguard children who've been identified, in conjunction with outside agencies such as social work.

The most extreme images and videos viewed by David and his colleagues plumb the depths of depravity. He agrees they have to switch off their own emotions.

Police Scotland monitors the wellbeing of officers in this type of work and there are strict rules to limit how much time they spend looking at the material.

They're not allowed to view it in the first or last hour of their shift, and one day a week is spent working from home, catching up on admin and emails.

"It's just a case of prioritising and laying out your day," David says.

"We start with a briefing every morning and we've got quite a substantial workload, and we just work our way through it the best we can.

"There are wellbeing measures in place and talking to counsellors and other people about what you're feeling and seeing can help unlock things."

Every week he and his colleagues walk past that warning on their office doors.

"We are reviewing footage of something that's already happened to these children," says David.

"But when we identify them and put the safeguarding measures in place, that's the most satisfying part of the job.

"I used to work in other areas of policing, like serious and organised crime and drug enforcement but I can honestly say that now kind of pales into insignificance.

"It doesn't compare to putting measures in place to make a child safe."