The Lampard Inquiry: What has happened so far?

PA

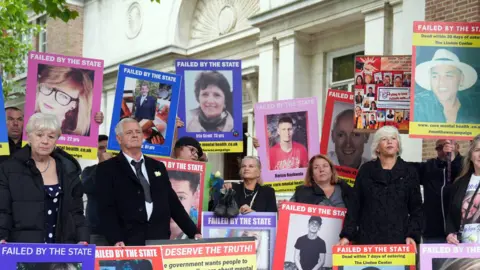

PAEight months into its 25-month timeline, the Lampard Inquiry is beginning to expose deep-rooted issues in NHS mental health services in Essex.

With more than 2,000 deaths in inpatient units between 2000 and the end of 2023, the inquiry is examining not only local failings but also whether these reflect wider national problems. Here is what has emerged so far.

A system under scrutiny

The inquiry is named after its chairwoman, Baroness Kate Lampard.

She is a former barrister who oversaw the NHS investigations into abuse by former television presenter Jimmy Savile.

It is primarily focused on Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust (EPUT), formed in 2017 from the merger of North and South Essex Partnership Trusts.

It is also looking at the deaths of patients from Essex at inpatient units run by private providers and facilities run by other NHS organisations, such as North East London NHS Foundation Trust.

The former health ombudsman Sir Rob Behrens said on average, 5% of all mental health cases received by his team between 2011 and 2023 were related to Essex.

He called the failures in care "the National Health Service at its worst".

During testimony from the relatives and friends of those who died, it emerged that they were individuals from a range of backgrounds, including a chef, bus driver, heating engineer, former head teacher, and parish councillor.

LAMPARD INQUIRY

LAMPARD INQUIRYLack of staff

The inquiry has heard evidence of a long-term reduction in registered mental health nurses, with increased reliance on healthcare support workers across England. This shift has been linked to reduced patient engagement and increased risk.

Former chief nurse Maria Nelligan told the inquiry this was because healthcare support workers were "cheaper" and said the move compromised therapeutic care.

Dr Paul Davidson, a consultant psychiatrist, described how staff across England were "rushed off their feet," contributing to a workplace culture where professionals feared being blamed "whatever decision they took".

Paul Scott, chief executive of EPUT, stated the trust had reduced its use of agency staff by 30%.

Poor data

STUART WOODWARD/BBC

STUART WOODWARD/BBCThe inquiry has also highlighted issues with data collection and transparency.

Deborah Cole, from the charity Inquest, described how there was no "complete set of statistics in relation to those who die in mental health detention".

Dr Davidson added: "There is good information in relation to deaths by suicide, [but] this is not a helpful tool by which to assess how mental services are being provided overall."

Baroness Lampard has warned that the inquiry may never uncover the full scale of deaths linked to failings in Essex mental health services.

She stated that while a figure would be published, it was likely to be approximate, due to incomplete or inconsistent data over the 24-year period under review

Regulating trusts

The inquiry has examined the complexity of the regulatory system overseeing NHS trusts.

Mr Scott described being "overwhelmed" by the number of regulatory bodies -19 in total - each issuing recommendations. This, he said, made it difficult to implement consistent change.

Away from the inquiry, in October 2024, the health secretary stated that the government intended to reform the regulatory system.

This was in response to a review of the way the Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspected trusts, called the Penny Dash Review, which said the framework was too complicated.

The Lampard Inquiry will consider the CQC's role in relation to events in Essex.

Analysis

Three systemic issues raised by the inquiry - staff shortages, poor data, and regulatory complexity - have been longstanding concerns.

The Royal College of Nursing, the CQC and a 2023 Public Accounts Committee report all flagged staffing shortages and burnout.

A 2023 review found Norfolk and Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust had lost track of patient death data, while a 2025 Health Services Safety Investigations Body (HSSIB) report called for a unified national dataset.

Regulatory reform is also under way following multiple critical reviews.

While Baroness Lampard is expected to reference these reports, the inquiry is also under pressure to uncover new evidence.

Some families have expressed concern regarding its pace, and limited focus so far on cultural change.

They have also noted that safeguarding issues, such as patients absconding from units, have received little attention - a relevant issue given a recent inquest into the death of an 18-year-old who died while on escorted leave from an EPUT unit.

Transparency and whistleblowing

Only 11 out of 14,000 staff came forward during the earlier non-statutory phase of the inquiry.

Baroness Lampard has said she will use statutory powers to compel evidence if necessary.

Mr Scott acknowledged that "closed cultures" existed at EPUT but said the trust was encouraging openness.

During a recent inquest into the death of a 16-year-old patient, a manager testified that staff were reluctant to raise safety concerns.

Brian O'Donnell, clinical lead at the St Aubyn Centre in Colchester, said there was a "real concern about safety on the wards, and staff are too worried to say anything about it".

Families have also raised concerns about delays in evidence disclosure, including a postponed inquiry session on a Oxevision, an infrared monitoring system, due to late submission of information by EPUT.

But Baroness Lampard said her decision to delay the hearing "should not be viewed in any way as enabling EPUT to avoid answering questions about its use of Oxevision".

ESSEX PARTNERSHIP UNIVERSITY NHS FOUNDATION TRUST

ESSEX PARTNERSHIP UNIVERSITY NHS FOUNDATION TRUSTWhat comes next?

PA

PAIn July, the inquiry will focus on the two former trusts that merged to form EPUT.

Mr Scott has said, when he arrived at the trust in 2000, the legacy of the merger was that "there was too much focus on governance and management and not enough on patient safety".

Families are calling for detailed scrutiny of individual deaths, but the inquiry is more likely to use selected cases to illustrate broader systemic issues such as governance, and culture.

Mr Scott has apologised for deaths under the trust's care and stated that he believes EPUT should remain the provider of mental health services in Essex.

Follow Essex news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, Instagram and X.