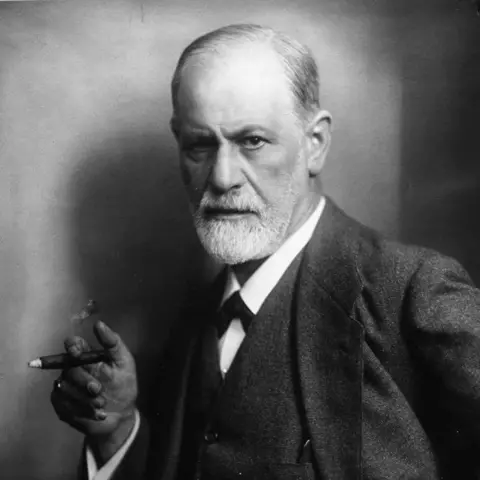

How Freud found the 'kindliest welcome' in London

Freud Museum London

Freud Museum LondonJune sees the re-publication of all the books written by famed psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, who spent the last year of his life living in London.

He was something of a celebrity when he arrived in the capital in 1938, but what did he think about his time there and did he leave any lasting impact?

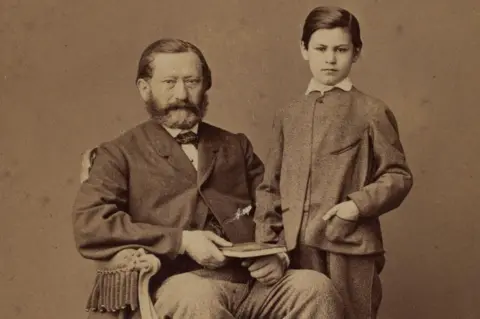

Sigmund Freud was born in 1856 in the Moravian town of Freiberg, in the Austrian Empire.

At the age of three his parents, Amalia and Jakob, moved the family to Vienna.

The young Sigmund excelled in literature, languages and the arts, all of which had a profound effect on his later thinking.

Freud Museum London

Freud Museum LondonIn 1881 he qualified as a doctor from the University of Vienna and specialised in neuropathology, becoming an associate professor in 1902.

But it was his book with Josef Breuer in 1895, Studies on Hysteria, which paved the way for Freud’s theories of psychoanalysis - the subject which he would become known as the founder of.

Psychoanalysis is a talking therapy where patients lie on a couch with their therapist behind them out of sight.

It means the patient can’t see a therapist's face and is encouraged to use free association and transference to share their deepest thoughts, with sessions sometimes necessary over several years.

"That was a new thing, the idea that if you talked to someone who was neurotic or mad, you might get some results rather than just locking them up and treating them quite violently," explains Lord David Freud, Sigmund Freud’s great-grandson.

"I think that was picked up and it was picked up almost universally by therapists."

Psychoanalysis is still widely used today – but there are dozens of forms of therapy that use similar or different techniques.

Freud is also widely known for the Oedipus Complex and looked closely at the unconscious mind of his patients. He was particularly concerned with their sex lives, dreams and repression with some of his ideas being considered controversial.

The founder of psychoanalysis had originally based himself in Vienna but in the early 1930s, being Jewish he came to the attention of Adolf Hitler’s Nazi Party, with his books being publicly burnt.

Austria was then annexed by Germany in the Anschluss of March 1938 and in June that year, at the age of 82, Freud left Vienna following negotiations and the payment of a fee to the Nazis.

Making his way to the UK, he travelled across Europe on the Orient Express, assisted by Princess Marie Bonaparte, a great-grandniece of Emperor Napoleon who was also one of his patients.

His departure from his home country was tinged with sadness.

Freud wrote to fellow psychoanalyst Max Eitingon on 6 June 1938, the day of his arrival in London: "The feeling of triumph on being liberated is too strongly mixed with sorrow, for in spite of everything I still greatly loved the prison from which I have been released."

Freud Museum London

Freud Museum LondonOn his arrival at Victoria station, crowds gathered to greet him. He was instantly recognisable to cab drivers.

"Freud was an international celebrity… a global brand famous all over the world. The story of his escape had been widely reported in the press,” says Dr Giuseppe Albano, director of the Freud Museum London.

Freud initially stayed at 39 Elsworthy Road in Primrose Hill, where he met the Surrealist artist Salvador Dali and he continued to see Marie Bonaparte among others.

But he was soon on the move again and took residence in the place he called home for the final year of his life - 20 Maresfield Gardens in Hampstead, which he bought for £6,500 with a mortgage and a down payment from the advance for a book.

By the late 1930s Freud was quite frail and suffering from jaw cancer so he didn’t indulge himself in London society.

"He declined many invitations," says Dr Albano. "He was active and received visitors to 20 Maresfield Gardens… Virginia and Leonard Woolf, they were his publishers. In January 1939, they came to talk about [his book] Moses and Monotheism."

Despite his initial concerns, Freud fell in love with London.

In Moses and Monotheism, he writes: "I found the kindliest welcome in beautiful, free, generous England.

"Here I live now, a welcome guest, relieved from that oppression, and happy again that I may speak and write."

Freud Museum London

Freud Museum LondonFreud’s life in Hampstead didn’t last much more than a year.

In extreme pain and with the blessing of Anna, his doctor and friend Max Schur administered a lethal dose of morphine in what has been described as an assisted suicide.

Freud died on 23 September 1939 at the age of 83, just after the outbreak of World War Two. He was cremated and his ashes placed in an urn in a mausoleum Golder’s Green cemetery.

His daughter Anna continued to live at 20 Maresfield Gardens until her death in 1982 and it was stipulated in her will that the house should become a museum devoted to her father.

It remains so today and includes many of Freud’s belongings, including the famous couch he used for his sessions.

K. Urbaniak

K. UrbaniakAs well as developing new ideas, Freud was a prolific writer and everything he put to paper, including books and research papers, was published from 1953 to 1974 in 24 volumes edited by James Strachey, with the assistance of Freud’s daughter Anna.

This June, the collection of books, known as the Revised Standard Edition (RSE), is being re-published having been edited by South African-based psychoanalyst Mark Solms.

The collection runs to more than 8,000 pages and costs about £1,500. The RSE’s publicists describe it as a "landmark set of books" that will "revise and enrich" Strachey’s originals.

Lord Freud believes the fact his great-grandfather was "such a good writer" was one of the keys to his success.

"He writes really compellingly and you’re picked up and dragged along as if you’re reading a novel when you read his books," he says.

"I am sure that is the fundamental reason he became so famous and established."

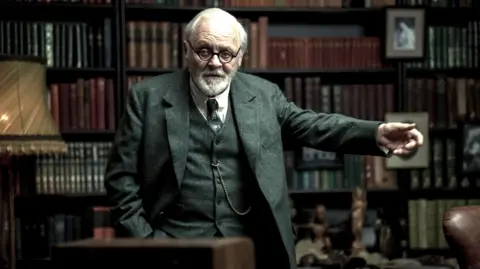

Last Session Productions Ltd

Last Session Productions LtdNo doubt the re-publication of his work will spark fresh interest in Freud, while a new film is also coming out in June, called Freud's Last Session, with Sir Anthony Hopkins playing the founder of psychoanalysis.

"We believe that Freud’s work has never been more alive… he revolutionised our understanding of the unconscious mind," says Dr Albano.

As for the part of the city he moved into, his legacy can still be felt beyond the museum in the high concentration of psychoanalytic practices in the area.

"London has a rich history in the development and practice of psychoanalysis," the museum director explains.

"When Sigmund Freud and his daughter Anna arrived in Maresfield Gardens in 1938… they significantly shaped Hampstead’s future as a psychoanalytic hub."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio London on Sounds and follow BBC London on Facebook, X and Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected]