Experts reveal fragments from rare Iron Age helmet

The Trustees of the British Museum

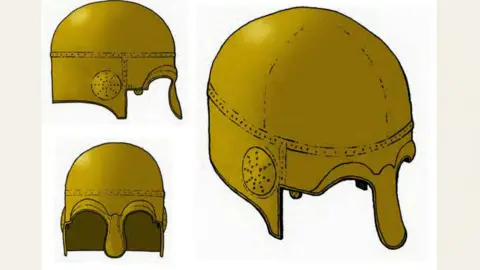

The Trustees of the British MuseumFragments of copper alloy unearthed at one of Britain's most important archaeology sites have been revealed to be parts of an incredibly rare Iron Age helmet.

The discovery was made by the British Museum during a 15-year project analysing 14 hoards of gold, silver and bronze torcs excavated at Snettisham, Norfolk, between 1948 and the 1990s.

"There are less than 10 Iron Age helmets in Britain and every single one is unique," said Iron Age curator Dr Julia Farley, explaining the discovery's significance.

Other insights included the revelation Iron Age craftsmen were capable of using techniques like mercury gilding and "we didn't know they could do this in Britain 2,000 years ago", she said.

'An archaeological jigsaw puzzle'

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumThe fragments - previously believed to be part of a vessel - were "one of the mysteries of the Snettisham Hoards", said Dr Jody Joy, who was the British Museum's European Iron Age curator when the project began in 2009.

"Metals conservator Fleur Shearman was putting together this material, almost like an archaeological jigsaw puzzle," he said.

"She invited us into the lab to look at what she had discovered... she was able to trace the outline of a nose area and where the eyes would go and suggested she had found a helmet."

Now the senior archaeology curator at Cambridge University's Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Dr Joy described it as "honestly, one of the most exciting things in my eight years at the British Museum".

The Trustees of the British Musuem

The Trustees of the British MusuemDr Farley, who co-edited The Snettisham Hoards with Dr Joy, explained: "There is a reason why everyone was so surprised in that room... helmets from Iron Age pre-Roman Britain, are just vanishingly rare.

"And this one is a one-off, it's got a kind of nasal bridge which is really unusual and these little brow pieces and it's all hammered out from incredibly thin sheet bronze, and that's a tremendously skilled thing to be able to do."

She believed it was probably not complete when it was put into the ground because so much was missing.

Dr Joy said it might have been an heirloom, or something beyond mending, or was simply intended as a container for other material when it was buried.

The helmet has yet to go on display, but "that's what the conservationists are working on", said Dr Farley, adding the warning it was "tremendously fragile".

What's so special about the Snettisham Hoards?

The Trustees of the British Museum

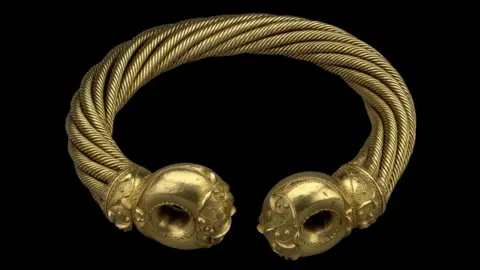

The Trustees of the British MuseumMore than 80% of the Iron Age (800BC to 43AD) torcs and bracelets known in Britain come from a field and woodland at Ken Hill, near Snettisham.

At least 400 torcs were discovered, more than 60 of which were intact or near intact - including the Snettisham Great Torc, one of the most elaborate golden objects from the ancient world.

The first discoveries were made by a ploughman and a series of further finds were made over more than 70 years by farm workers, metal detectorists and a British Museum-led excavation.

Most were buried in about 60BC, with some finds dated to the early Roman period, and they are one of the biggest concentrations of precious metal from prehistoric Europe.

Despite its importance, the hoards had never been fully published, which is why the British Museum began this project, in partnership with Norwich Castle Museum, which also holds some of the finds.

'Amazing torc technology revealed'

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumThe torcs and other fragments were examined in detail using the latest cutting-edge scientific technology.

"British Museum scientists uncovered the finer details of the objects using an electron microscope," said Dr Joy.

"You can see wear patterns at the back of the object and you can see polishing on the underside of the terminals where they would have been rubbing against either the body or clothing.

"So these things would have been worn for a long time or worn very intensively, and that was a really big insight."

The scientists worked with a metal worker "and he showed how intensive the process was, how long it would have taken to get the wires into the same circumference and twist them together," he added.

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumThe sophisticated finishing skills of the Iron Age metal workers, including the use of mercury gilding, was another surprise.

Dr Farley said: "They're taking bronze torcs and gilding the surface with an amalgam of mercury and gold - an amazing technology that's really hard to learn and very toxic. You wouldn't want to be the person doing it.

"The other thing I'd add is every single one of these objects is unique, while we live in a world that is standardised.

"These people lived in a world where these unique and personal objects, which they wore on their bodies, would have had histories and stories and names."

Julia Farley

Julia FarleyAn additional insight was confirmation the torcs were "probably worn by men, women and even younger people", rather than kept for high status men.

Dr Farley said: "When people imagine someone wearing the Great Torc, they're imagining a man with a twirly moustache, but actually when you know the sheer breadth of sizes [found at Snettisham] we should assume they're being worn by everybody."

From an age of torcs to an age of coins?

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumWhy were so many torcs laid to rest at Ken Hill within such a short period of time?

The science suggested they were in circulation for decades beforehand and many showed signs of repair, with one visibly mended with an organic twine, before they were interred.

Dr Farley said: "To us it seems really weird to put valuable stuff in the ground unless you are trying to hide it.

"It's probably a sacred location where people are making these offerings - there's even a Roman temple there later."

But there is another insight offered by the research related to the introduction of coinage in the late part of the last century BC.

Dr Farley said: "Torcs are unique, individual, you wear them on your body [while] coins are mutually indistinguishable. You can give them to lots of people and they can be scattered and brought back.

"So the two things don't work well together.

"Our theory is these torcs are too special, too unique and too important to be melted down and turned into coins, and instead people decided to have a ceremony to bring people together and put them in the ground."

'Rich and complex Iron Age lives'

Jody Joy

Jody Joy"I think there's an inherent bias people have that you have to have a pyramid or a temple or a king with a crown to represent a complicated society," Dr Joy said, reflecting on the 15-year long analysis.

And Norfolk appears to have had a particularly dynamic Iron Age society.

"They had the mechanism to make this stuff, to source the gold, to wear it in a society setting which we don't really understand and then put it in the ground in a complicated way," he said.

Dr Farley agreed, adding: "These people are just as sophisticated and intelligent as we are. They live these rich and complex lives.

"I hope people will look at the material from Snettisham and feel a little bit of both of those things - recognition, but also the the wonder of looking into a different world."

The Trustees of the British Museum

The Trustees of the British MuseumFollow Norfolk news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, Instagram and X.