The Conservative Party faces problems - is its leader one of them?

BBC

BBCListen to Henry read this article

"Could this be like the 1920s where the Liberals got overtaken by Labour – but this time it's the Conservative Party being overtaken by Reform?"

It's an interesting question – perhaps a little niche. But it's certainly not a question you'd expect to find a senior member of Kemi Badenoch's team openly pondering.

The shadow cabinet minister went on to stress that they were more optimistic: that the resilience of what is often called the world's most successful political party should never be underestimated.

Yet it's not so rare to find Conservative MPs entertaining the demise of the party under whose banner they were elected only last year.

Why? Because since July – when the Conservatives were not just turfed out of office but reduced to their fewest MPs ever – things have only got worse.

Getty Images

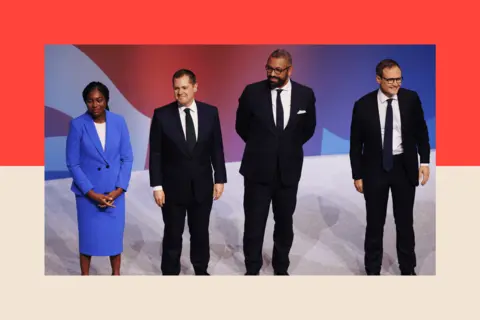

Getty ImagesThe initial excitement of a leadership contest and the opportunity to renew their party in opposition has given way, for many Conservative MPs, to a deep and deepening despondency.

And while almost nobody believes that Kemi Badenoch, leader of the party for just under seven months, is the problem, more and more Conservatives admit to seeing her as a problem.

"It's pretty bad," says one Conservative adviser. "I don't think you would find many of her supporters at all who would either tell you it's going well or that they expect her to be there at the general election."

Another senior Conservative puts it more starkly. "This is a hugely important crossroads for the party. Trying to win an election again or just becoming a sort of heritage party that shrivels."

How Conservative strength crumbled

The immediate cause of these statements – one about Badenoch, the other about the party more generally, both utterly fatalistic – was the local election results at the start of May, a grim reminder for the Conservatives that the only way isn't up.

What began as expectation management, that the Conservatives might lose control of every council they held at the start of the night, became a prophecy. Crucially, the local elections proved that the rapid surge of Reform UK in the polls was real at the ballot box too.

The results also made clear that the challenge facing Badenoch is a dramatically distinctive one.

The Conservatives last left government in 1997, and in the following set of local elections in 1998, their new leader William Hague made modest gains.

When Labour lost office in 2010, their new leader, Ed Miliband, made gains at the local elections the following year. There is a template for how defeated parties fare in their early period out of office – and Badenoch's Conservative Party is diverging from it significantly.

In fact, new analysis by the BBC's Political Research Unit shows that things have got worse for the Conservatives even in the few weeks since the local elections. The Conservatives have lost 47 more councillors since polling day, a rate of about two a day.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThere are diverse reasons for this – six (including two this week) have defected to Reform UK, whereas others who have quit have generally left to become independents. One has defected to Labour. Three have died. And it's worth noting that on the other side of the ledger, one independent councillor has defected to the Conservatives since the start of May.

While not completely unheard of, it is unusual for a party to lose so many councillors in such a short period of time and will be interpreted by some as another sign that the pillars of Conservative strength are continuing to crumble.

In the same time period, Reform have gained 19 new councillors, both through defections and by-elections, although they have also lost five. It is striking that in no council in the country has a Conservative-Reform coalition materialised, despite much speculation – underscoring that, even at the most local level, the two parties are vying directly with each other.

The Conservatives' polling position has deteriorated since the local elections too. A YouGov poll last week put the party in fourth place on 16%, their lowest share with the pollster ever.

While probably an outlier – a new poll this week had the Conservatives back in third – falling even temporarily to fourth was a blow to Tory morale at the start of what became a difficult week for its leader.

Badenoch's difficult week

Badenoch's performances at Prime Minister's Questions (PMQs) had been seen by her colleagues to be steadily improving. That changed on 21 May when Sir Keir Starmer opened the session with an announcement that he was U-turning on the winter fuel allowance. Badenoch proceeded with her planned questions anyway, only coming to the winter fuel allowance midway through.

Badenoch denied what many of her own MPs believed – that she had simply failed to notice the significance of what the PM had said. "Lots of people who have never done PMQs all have lots of suggestions," Badenoch said.

PA Media

PA MediaSome members of the team preparing Badenoch for PMQs have been urging her to change her approach, advising her to deploy more jokes in an effort to break through in what is typically her highest-profile event of the week. Badenoch disagrees.

"She wants it to be more serious," says a party source. "She feels PMQs should be a proper exchange of arguments and views."

An oddity of PMQs at present is that, given Reform's surge, Starmer often uses Badenoch's questions to jab at Reform, who have a tiny Commons presence.

Some argue that in a funny way the Conservatives are a victim of Starmer's unpopularity: Labour's polling decline has been so fast that voters who are unwilling to forgive the Conservatives are flowing to Reform instead.

'She's just vacated the playing field'

Unexpected though it may have been, Reform's success arguably feeds on a crucial early strategic call Badenoch made.

During her leadership campaign, a point of difference between Badenoch and her rivals was policy. Not necessarily what party policies themselves should be, but more fundamentally, when and whether to have policies.

She argued that the Conservatives needed to take the time to go back to first principles and work out what the government should and should not do. This, Badenoch was explicit, would take time.

In practice that has meant Badenoch repeatedly refusing to be drawn on policy questions, instead launching a string of policy reviews which will weigh up what direction to take the party in.

To many of her colleagues we've spoken to, that is being increasingly revealed as naive at best.

"The way in which she's just vacated the playing field has been a total disaster," one senior Conservative says. "Reform has become the de facto opposition. And that's because of a conscious choice she and her team made."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEven some shadow cabinet ministers – each of them responsible for the policy reviews in their areas – agree. "We need more policy sooner," says one.

Another urged Badenoch to do more to "articulate our values" even while sticking to her policy development timetable.

Others argue that criticism of Badenoch on policy development is wide of the mark. A shadow cabinet minister pointed out that Badenoch had said she would reverse Labour's policies on inheritance tax on farms and VAT on private school fees, as well as changing the Conservative position on net zero targets and the European Convention on Human Rights.

"It's not that we're not saying things," says the shadow minister. "It's that people don't want to listen to us."

Redundancies at Conservative Party HQ

Accompanying that strategic debate are more mundane frustrations, many of them stemming from money – or the lack of it.

True, political parties often shrink their staffing operations a little at this point in the cycle, having tooled up for the general election. But at Conservative Campaign Headquarters (CCHQ), a string of voluntary, then compulsory, redundancies were especially severe, prompting so much briefing that Badenoch was moved to write to party members assuring them the rebuild was strategic rather than due to a shortage of funds. "Ignore ill-informed media reports from the disgruntled," she says.

Shadow cabinet ministers have repeatedly complained of going without advisers, several of them being told the party does not have enough money for them to hire yet.

"You go from having a whole department of thousands of civil servants filling your red box with briefings to working out how to respond to the government in the House of Commons all by yourself," says one shadow minister, sitting alone at a table in parliament.

Badenoch's defenders – and indeed some of her critics – say that both the money and personnel issues are yet more facets of her miserable inheritance.

"People don't realise how bad a state CCHQ was in," one MP says. "A lot of work has had to go into getting the party back on its feet, and I don't think it fully is yet."

Opposition parties are funded by a scheme known as Short Money. While there is a fixed sum for the staffing costs of Badenoch's office as leader of the opposition, the rest of the money given to the Conservatives is calculated from a formula on the basis of the number of seats and votes they won at the general election. Both were low – so, as a result, is the Conservatives' income.

Time for a 'pact' with Reform?

Badenoch did not exactly have the luxury of choice for her shadow cabinet, given its members constitute almost 20 per cent of Conservative MPs. Still, there are frequent complaints that some have taken to opposition with significantly more energy and commitment than others, and that Badenoch ought to promote newly-elected Conservatives to senior roles sooner rather than later.

Reshuffle rumours are the preserve of any political party. But those complaints, as with all the others, take on a greater urgency while Reform is lurking.

A few months ago, the word that probably figured most often in conversations with Conservatives about Reform was "pact" – should there be one between the two parties come the next general election.

Now it is probably "existential" – the crisis the Conservatives have been plunged into by Reform's success.

"Right now it would not be a pact," says one Conservative MP, "it would just be us folding into Reform."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesEven those who believe the Conservatives will overpower Reform in time wonder at what point more pessimistic Conservative MPs might follow the logic of their own predictions and defect.

Top of many of her colleagues' lists is Suella Braverman, the former home secretary.

Asked earlier this month whether she would join Reform, Braverman spoke of her "many decades" of commitment to the Conservative Party but warned her colleagues that "Reform is here to stay".

What worries some Conservatives more is not defections of current MPs but a brain drain of future MPs and advisers – the kinds of people who keep the ecosystem of a political party healthy.

They warn of a "crossover point" where ambitious young people on the right entering politics might decide it makes more sense to sign up to Reform than to join the Conservatives.

Questions around Badenoch's future

For all their frustration, many Conservative MPs are still sticking to the view that Badenoch ought to be given longer to prove her worth. For them, the next set of local elections just under a year from now will be the pivotal moment – not least because they coincide with elections for the Scottish and Welsh parliaments too.

A shadow cabinet minister says: "Realistically you need to give any leader, including this one, at least two years to show their worth."

Others disagree. "People say 'you can't change leader again, you'll look mad'," says one senior Conservative. "Well I remember all that with Liz [Truss]. People said the country wouldn't allow it. Actually the country was just relieved."

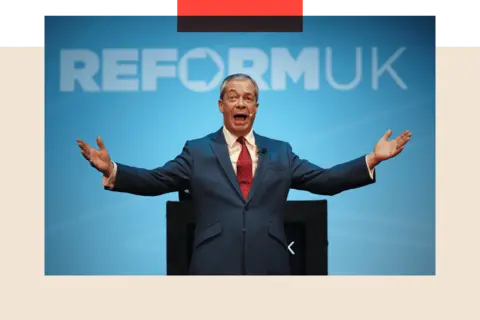

One crucial factor in Badenoch's favour is that, beneath the loud despair, there are still plenty of Conservatives who believe Reform's surge will fizzle out. One shadow cabinet minister says that just as Reform UK leader Nigel Farage was the beneficiary of a "speeding up" of politics, he will soon become a victim and be seen by the public as "old news".

Others believe that Farage's prominence masks how thin Reform's bench is. "You can't win a general election or be the largest party as a one-man band. Farage will have to find a way of sharing the limelight."

Those the words of a senior figure from the last Conservative government.

Last as in most recent? Or last as in final?

Overwrought it may sound, but there really are plenty of Conservatives now entertaining those questions.

Additional reporting by Peter Barnes and Oscar Bentley.

Top picture credit: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.

Sign up for our Politics Essential newsletter to keep up with the inner workings of Westminster and beyond.