I hope I live long enough to get my autistic grandson out of hospital

BBC

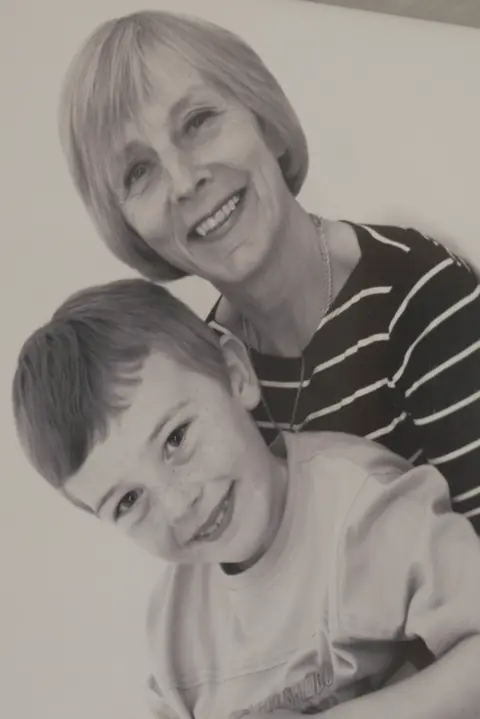

BBCAn 81-year-old granny has told the BBC she hopes she lives long enough to get her autistic grandson out of the hospital he has been stuck in for two years.

Dorothy Lafferty said doctors had long ago agreed that 28-year-old Andrew does not need to be cared for in hospital but there is nowhere suitable for him to go.

He needs a team of carers and a house that is quiet because noisy environments make his anxiety worse.

New figures due out later are expected to show there has been an increase in the numbers of people with learning disabilities and autism who are stuck in hospital or inappropriate placements far from home.

This is despite ministerial pledges to have remedied the problem by March this year.

Ministers first promised to move the majority of people stuck in hospital to a home of their own in the community in February 2022.

Dorothy Lafferty

Dorothy LaffertyThey started recording the figures and a year ago the first dynamic support register was published.

The latest figures show that 1,545 people were on the dynamic support register on 26 September, of whom 486 were classified as urgent.

There were 195 people in hospital, of whom 85 were classified as delayed discharge.

When the register was first published a year ago there were 1,243 people on the register, with 455 classed as urgent.

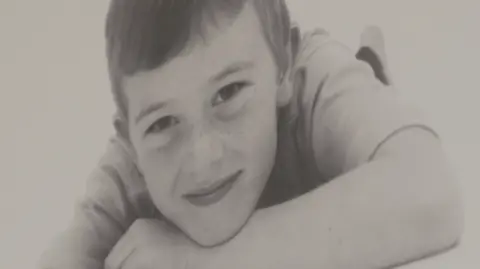

Andrew has been in a 20-bed adult mental health unit at Stobhill hospital in Glasgow for two-and-a-half years.

For two of those years he has been recorded as a delayed discharge and should have been allowed home - but there is no suitable house for him to go to.

His 'nana' Dorothy has cared for Andrew since he was two, when his mother needed support to help her deal with brain cancer.

His mother died from the cancer when he was 12 and Andrew became extremely anxious and struggled to cope.

Dorothy Lafferty

Dorothy LaffertyDorothy, from Bishopbriggs in East Dunbartonshire, says Andrew went to a mainstream school and was doing well but the loss of his mother left him distraught.

She says he could not understand how someone he prayed for could have died.

After leaving school, he struggled in placements and flats because they were too noisy for him.

He was then placed on a mental health ward when his symptoms became severe but was assessed as being fit to leave with the right support two years ago.

Like the hundreds of others with learning disabilities or autism who are stuck in units or hospitals, there is still nowhere for him to live.

Experts say there is a lack of suitable housing, a shortage of care staff and sometimes a failure to prioritise those behind locked doors.

In a note to the BBC, Andrew wrote: “I would like a place of my own with not a lot of people there."

He said he felt scared of leaving hospital because he had been there for so long.

Dorothy Lafferty

Dorothy LaffertyHis autism means he struggles to eat hospital food and is often too anxious to sit with others in the dining room.

His gran regularly makes him tuna sandwiches and takes them to him in the hospital.

Dorothy says Andrew finds many situations too stressful and worries about who will look after him when she is gone.

"I keep thinking I’m so lucky at 81 to be like I am," she said

"I’m able to get out and about and that’s a big plus for me.

"If I can keep this going until I see Andrew out of there I’ll feel like I’ve achieved something in life."

Andrew has a care team in place but no home to go to.

Dorothy says she has spent hours in the library researching accommodation and has been to dozens of meetings but there has been no progress.

She says she and Andrew are very worried about what will happen next.

“He said to me last week: ‘Nana, is there a chance that you could live until you're 100'?"

When Dorothy told him not many people live that long, he said: "I’ll feel as if my life’s ended if anything happens to you because I depend on you so much.

"I can’t imagine what life would be like without you."

Dorothy said: "I want to live long enough to see Andrew settled. That’s my one aim in life. That’s all I want.”

The dynamic support register which monitors how many patients are in unsuitable accommodation was meant to be accompanied by a national oversight panel.

This was meant to hold local authorities and health and social care partnerships to account but it has never happened.

Government advisor Dr Anne Macdonald said not enough progress had been made and that the system was “failing” people with complex support needs.

"People have the right to live in their local community, to live near family and friends and have an ordinary life like the rest of us would want," she said.

"Those with complex support needs who are currently stuck in hospital or living hundreds of miles from home in inappropriate out of area placements – we’re not doing enough for those people and I’d go as far as to say we’re failing them and their families.”

The Scottish government said in 2013 that within five years people with learning disabilities, autism and complex care needs who were in facilities outwith Scotland should be supported to live nearer their family in Scotland.

The policy to move people out of institutional care and closer to family follows decades of promises to get people with learning disabilities out of big hospital institutions and into the community - but a number seem to have become stuck in the system.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSocial Care Minister Maree Todd said she was "very disappointed at the slow progress" that was being made.

"The Coming Home report told us that we needed to do some things in central government and we’ve pretty much completed those things," she told the BBC.

"We’ve created the dynamic support register, that gives us a really good idea of data. We know now who is in the system and where they are, and that’s informing local authorities and local health boards.

"But we haven’t made the progress in driving down the numbers and that is very disappointing to me.”

Derrick Pearce, the chief officer of East Dunbartonshire Health and Social Care Partnership (HSCP), which is handling Andrew's case, said it supported a wide range of social care provision in the local community.

"However there are times when identifying a care provision which will be successful in meeting complex care needs may take longer than we would like in order to ensure a successful long-term discharge from hospital," he said.

“In all cases, including Andrew's, significant multi-disciplinary assessment and care planning with consideration to both medical and social models of support is carried out to establish a bespoke model of care in partnership with family and carers."

“By continuing to work closely together we are hopeful we will establish a person-centred care plan whilst identifying suitable accommodation based on specific housing and health needs whilst ensuring and safeguarding the success of these plans to enable safe and independent living within the community.”