Tracking the world's major cocaine route to Europe - and why it's growing

BBC

BBC"The Albanian mafia would call me and say: 'We want to send 500kg of drugs.' If you don't accept, they kill you."

César (not his real name) is a member of the Latin Kings, a criminal drug gang in Ecuador. He was recruited by a corrupt counternarcotics police officer to work for the Albanian mafia, one of Europe's most prolific cocaine trafficking networks.

The Albanian mafia has expanded its presence in Ecuador in recent years, drawn by key trafficking routes through the country, and it now controls much of the cocaine flow from South America to Europe.

Despite Ecuador not producing the drug, 70% of the world's cocaine now flows through its ports, Ecuadorean President Daniel Noboa says.

It is smuggled into the country from neighbouring Colombia and Peru – the world's two largest producers of cocaine.

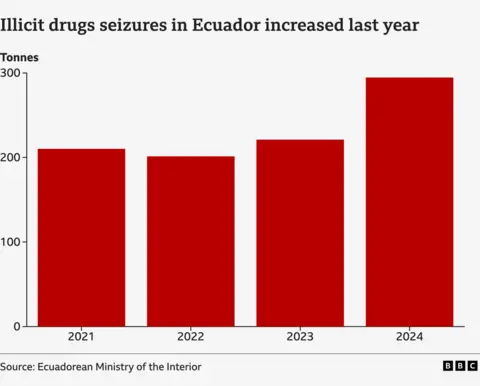

Police say they seized a record amount of illicit drugs last year, the majority of it cocaine, and that this indicates total exports are on the rise.

The consequences are deadly: January 2025 saw 781 murders, making it the deadliest month in recent years. Many of them were related to the illegal drug trade.

We spoke to people in the supply chain to understand why this crisis is worsening – and how rising European cocaine consumption is fuelling it.

César, 36, first started working with cartels when he was 14 years old, citing poor job opportunities as one factor.

"The Albanians needed someone to solve problems," he explains. "I knew the port guards, the transport drivers, the CCTV camera supervisors."

He bribes them to help smuggle drugs into Ecuador's ports or to turn a blind eye – and the occasional camera.

After cocaine arrives in Ecuador from Colombia or Peru it is stashed in warehouses until his Albanian employers become aware of a shipping container that will be leaving one of the ports for Europe.

Gangs use three main methods to smuggle cocaine into shipments: hiding drugs in cargo before it reaches the port, breaking into containers at the port, or attaching drugs to ships at sea.

Sometimes César has made up to $3,000 (£2,235) for one job, but the incentive is not just money: "If you don't do a job the Albanians ask for, they'll kill you."

César says he feels some regret over his role in the drugs trade, particularly what he calls the "collateral victims".

But he believes that the fault lies with the consumer countries. "If consumption keeps growing, so will trafficking. It will be unstoppable," he says, adding: "If they fight it there, it will end here."

Ordinary workers, not just gang members, get caught in this supply chain.

Juan, not his real name, is a truck driver. One day he picked up a tuna shipment to take to the port. He says that something seemed off.

"The first alarm bell was when we went to the warehouse and it only had the cargo, nothing else. It was a rented warehouse, no company name," he recalls.

"Two months later, I saw on the news that the containers had been seized in Amsterdam, full of drugs. We never knew."

Some drivers unknowingly transport drugs; others are coerced – if they refuse, they are killed.

European gangs are drawn to Ecuador for its location but also its legal exports, which provide a convenient way to hide illicit cargo.

"Banana exports make up 66% of containers that leave Ecuador, 29.81% go to the European Union, where drug consumption is growing," explains banana industry representative José Antonio Hidalgo.

Some gangs have even set up fake fruit import or export companies in Europe and Ecuador as a front for illicit activities.

"These European traffickers pose as businessmen," says "José" (not his real name), a prosecutor who targets organised crime groups and who spoke anonymously due to threats he has received.

One notorious example is Dritan Gjika, accused of being one of the most powerful Albanian mafia leaders in Ecuador.

Prosecutors say he had stakes in fruit export companies in Ecuador, and import companies in Europe, which he used to traffic cocaine. He remains on the run, but many of his accomplices faced convictions after a multinational police operation.

Lawyer Monica Luzárraga defended one of his associates and now speaks candidly about her knowledge of how these networks operate.

"In those years, banana exports to Albania boomed," she says.

She appears frustrated that authorities did not put two and two together sooner that criminal groups were using this as a front: "The entire economy here is stagnant. Yet one item that has increased in exports is bananas. So, two plus two equals four."

Why exports are rising

At Ecuador's ports, the police and armed forces try to control the situation.

Boats patrol the waters, police scan banana boxes for bricks of cocaine – even police scuba divers search for drugs hidden beneath ships.

Everyone is heavily armed, even those simply guarding banana boxes before they are loaded into shipping containers. This is because if drugs are found during a search, a corrupt port worker would likely be involved, and it could trigger a violent incident.

Despite these efforts, police say the amount of cocaine being successfully smuggled out of Ecuador has reached a record high. Rising demand and economic factors are blamed.

Nearly 300 tonnes of drugs were seized last year – a new annual record, according to Ecuador's interior ministry.

Major Christian Cozar Cueva of the National Police says that "there has been about a 30% increase in seizures headed for Europe in recent years".

This increase in cocaine shipments has made it more dangerous for those caught up in the supply chain.

Truck driver "Juan" says the rise of "container contamination" makes him more vulnerable.

He says officials seized a container the day before with two tonnes of drugs: "It used to be kilos, now we talk about tonnes."

"If you don't contaminate the containers, you have two options: leave the job or end up dead."

An economy battered by the Covid pandemic left more Ecuadoreans vulnerable to gang recruitment.

A state that was financially stretched post-pandemic, a security force which had less experience dealing with organised crime, and previously lax visa rules facilitated European gangs' presence there post-2020.

Monica Luzárraga says 2021 was the year when the "Albanian mafia infiltration took off".

She says this period coincided with an "influx" of Albanian citizens and a spike in banana exports, including to Albania.

"This is a lucrative business that harms Ecuador and benefits criminal organisations. How can we accept an economy built on suffering?"

A message to Europe

This ire toward foreign cartels is unsurprising, given their contribution to rising violence.

But one thing some traffickers and those fighting them agree on: the trade is fuelled by consumers, particularly in Europe, the US and Australia.

UN data shows global cocaine consumption has hit record levels. Its surveys suggest the UK has the world's second highest rate of cocaine use.

The UK's National Crime Agency (NCA) estimates the UK consumes about 117 tonnes of cocaine annually and has the biggest market in Europe.

Evidence suggests consumption in the UK is rising.

The UK Home Office's analysis of wastewater suggests cocaine consumption increased by 7% from 2023 to 2024. NCA operations seized about 232 tonnes of cocaine in 2024, compared with 194 tonnes in 2023.

The NCA's deputy director of threat leadership, Charles Yates, says this makes the UK the "country of choice" for organised crime groups who profit from the high demand.

He estimates the UK cocaine market is worth around £11bn ($14.2bn), and criminal gangs make about £4bn a year in the UK alone.

Those fighting these gangs in Ecuador, like prosecutor José, say it is down to "countries whose nationals are consumers to exercise greater control" on those financing the trade.

Its victims take many forms.

For Mr Hidalgo it is the banana exporters suffering reputational and economic damage. For Ms Luzárraga, it is "children, adolescents who are being co-opted by criminal gangs".

"In Europe there are citizens willing to pay large amounts of money to have the drugs they consume. The drugs that are ultimately costing the lives of Ecuadorean citizens."

The NCA stresses that as well as these "catastrophic" effects on communities along the supply chain, cocaine use is claiming additional casualties in users due to cardiovascular and psychological impacts. Cocaine-related deaths in the UK increased by 30% in 2023 compared to 2022, to 1,118.

The NCA also warns that the drug exacerbates domestic violence.

He is clear law enforcement's efforts to tackle the supply aren't enough: "Supply side action on its own is never going to be the answer. What's really important is changing the demand."

From drug gang members to the country's president, this is Ecuador's message to Europe, too.

President Daniel Noboa, who is standing for a second term in the presidential election run-off on 13 April, has made fighting criminal gangs one of his main priorities and deployed the military to tackle gang-related violence.

He told the BBC: "The chain that ends in 'UK fun' involves a lot of violence."

"What's fun for one person probably involves 20 homicides along the way."

Additional reporting by Jessica Cruz