'I donated a kidney to my son-in-law'

BBC

BBCLast year more than 5,000 people in the UK were on the waiting list for a kidney transplant. There is a national shortage of all organs, and the impact on daily life for those needing one can be huge.

But kidneys can also be given by live donors. Last year 832 people did just that after months of preparation and assessment.

BBC North West health correspondent Gill Dummigan followed one operation in Manchester.

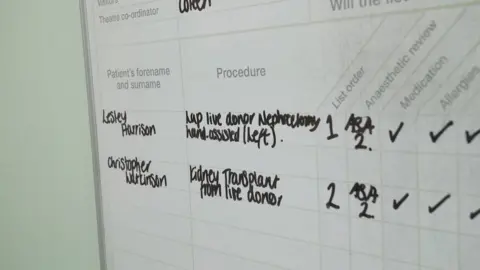

I first meet Lesley Harrison the night before her kidney transplant operation, sitting in a side room at the Royal Manchester Infirmary.

"It would be daft not to be nervous, wouldn't it? I'll be glad when it's over," she says.

Lesley isn't the one receiving a kidney – she's giving one to her son-in-law Chris.

She's one of just a few hundred people each year in this country who donate one of their own healthy kidneys to save someone else's life.

I ask her why she's decided to do it.

"Because he needs one, and I have one to spare so...,” says Lesley before welling up and pausing.

"They can't be a normal family while he's like this so hopefully when he has my kidney they can get back to having a normal life."

Ken, Lesley's husband, is there for moral support.

He also offered to donate his own kidney but was ruled out because of his medication.

Ken says he fully supports her: "I don't see any problem with it."

Chris Watkinson, Lesley's son-in-law, has IGA nephropathy, an autoimmune disease which has destroyed his own kidneys, left him on dialysis and unable to work.

He can barely make it upstairs without needing a rest.

He knows a successful transport would transform his life.

"To have another portion of time, if it's six years fine, if it's longer, even better. Just to get my life back," he says.

I ask the pair if they've spoken much about the emotional enormity of what's about to happen.

“I don't think we've dwelt on it," says Lesley.

Chris says he is always conscious of the impact on Lesley. "I always ask you how you are feeling."

"And I always probably just say I'm fine," finishes Lesley.

"Yes, you've always been very blasé," says Chris, who then looks serious.

"It's a huge thing. I probably don't say it to you enough but thank you."

Lesley wells up again and waves him away.

To get to this point it has taken months of tests and scans to make sure Lesley and both of her kidneys are healthy.

The kidneys need to be equally effective, to ensure that both Lesley and Chris can stay healthy with only one.

Mental preparation is also important.

Live donors are assigned a transplant co-ordinator whose job is to purely look after that donor's interest. Lesley's is Lisa Mulreid, who says it takes about six months to make sure someone is ready.

"I think they need that time... so we can give them the right counselling and education throughout for them to decide this the right thing for them to do.

"It's massive and it's not for everybody. Sometimes people feel obligated that a relative might need a transplant but you have to be the right kind of person to undergo it really," she says.

The most recent annual figures for the UK - up to April 2023 - show 832 people were living kidney donors. The number of people waiting for a kidney transplant is 5,361.

Most organs come from deceased donors, and there is a shortage of all of them. But kidneys are among the few which can be gifted by someone who is still alive.

Zia Moinuddin is the clinical lead for kidney transplants at Manchester Royal Infirmary, one of the biggest living organ transplant centres in the country.

He describes living donations as "the gold standard".

"The kidneys tend to function immediately which improves not just one-year but also five-year survival rates as well," he says.

Different centres use different techniques. Some have the donor and the recipient in operating theatres next door to each other so the kidney can be swapped almost immediately.

Others, like Manchester, carry out the operations one by one in the same theatre. The organ has to go in an icebox between operations but this technique allows the same consultant to carry out both removal and replacement surgeries.

So the next morning it's Lesley sitting in a surgical gown, waiting to be called to theatre. Chris sits with her for moral support. The pair chat and joke until she's called away.

Chris gives her a big hug and tells her she'll be fine, looking after her as she walks down the corridor. Within the hour she is in theatre.

The operation uses keyhole surgery to cut the connective veins, arteries and tissue which bind Lesley's kidney to the rest of her.

The instruments have a small camera which allows the surgical team to see what's happening on a screen above the operating table.

The kidney itself is moved and protected by the surgeon's own hand, which goes in through a separate opening.

Zia explains the hand is used both as a guide and a safety measure.

"It keeps other important structures out of the way and creates the feel for us to be able to operate and detach the kidney," he says.

"In a donor nephrectomy we need a good length of blood vessels on the kidney for us to be able to safely transplant it so we tend to go quite close to the donor's major blood vessels.

"The safety of the donor is paramount so we want to ensure that there's no damage to any of the surrounding structures."

It takes about two hours to carefully detach Lesley's kidney. Once removed, it's flushed through with a cooling fluid and kept in an icebox to prevent any damage while Lesley is sewn up, taken to recovery, and the theatre is scrubbed down.

Now it's Chris's turn.

'Fresh batteries in'

Chris has been here before. Seven years ago he received one of his mum's kidneys but the disease has now damaged that as well.

He tells me initially he didn't want another live donor.

"I felt like I'd used up my luck a little bit and I didn't want to put anybody else at risk for my continued health problems," he says.

"It was one of my doctors who said to me - if people are offering then you should be prepared to let them help."

Chris still has both of his own kidneys, as well as his mum's, so now he'll have four.

Zia says the new kidney goes in front rather than round the back.

"It goes low down in the belly. It makes the operation easier and makes the new kidney more accessible if we want to biopsy it or do anything to it in the future."

Chris's operation takes about three hours and goes well. It's now a question of waiting to see how the transplant has worked.

Six weeks later I catch up with the pair, enjoying the sunshine at a local beauty spot near Chris's home in Poulton-le-Fylde, Lancashire.

Chris feels "like someone's put fresh batteries in", adding: ”I feel great.”

The road for Lesley has been less smooth.

She has been surprised by how tired she felt. She also ended up in A&E after suffering abdominal pains but thinks she may have overdone things after the operation.

She is now recovering well though, and says she's feeling "really good now" and is looking forward to going on holiday.

"Now that I've been checked over and know that it's just part of the healing process, I feel better."

Chris tells her it was hard to hear about that, knowing the circumstances, but Lesley plays it down.

"I'd do the same thing again," she says.

Donors are given annual check-ups for the rest of their lives.

Transplant co-ordinator Lisa says this helps other, unrelated, health issues to be picked up more quickly.

She says she loves her job, working with living donors who are "a special group of people".

"It's the only operation anyone will ever have that's not in their own best interests (physically).

“It's not to improve their quality of life or their health, or to save their life, they're doing it purely for someone else's benefit.”

Chris is now looking forward to the years ahead with his family, thanks to Lesley's decision.

He says he is in awe of what she has done.

"She's so kind, selfless, brave... I mean, how do you repay that? I don't think you can really, can you?"

Watch BBC North West Tonight on BBC One at 18:30 and on iPlayer. Listen to the best of BBC Radio Manchester on Sounds and follow BBC Manchester on Facebook, X and Instagram. You can also send story ideas to [email protected]