Pioneering trial could 'switch off' arthritis

BBC

BBCPatients are taking part in a trial that scientists hope could ultimately lead to a cure for rheumatoid arthritis.

The AuToDeCRA-2 study seeks to prove it is possible to train white blood cell commanders - dubbed the "generals" of the immune system - to order other "soldier" cells to stop attacking healthy tissues.

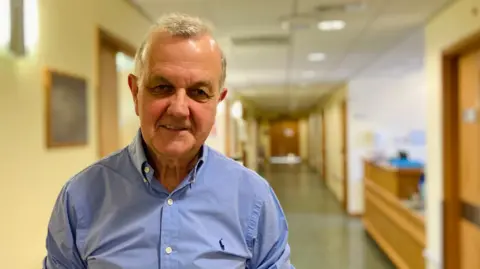

Prof John Isaacs, who has worked on the condition for 35 years and is leading the research, believes this could make it possible to "switch off" rheumatoid arthritis.

Trial participant Carol Robson, from Jarrow in South Tyneside, says the worst part of living with the disease is the pain, but if the research helps ease suffering "that would be wonderful".

The study, funded by the charity Versus Arthritis and the European Commission, is being run by Newcastle University and Newcastle Hospitals.

"It's pioneering," Prof Isaacs claims. "There are only one or two other groups around the world doing similar work."

Training the 'generals' to stay calm

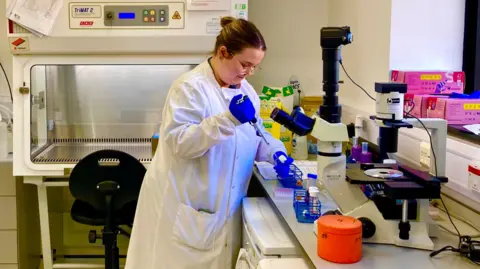

In this latest research, now in its second phase, certain cells are isolated from a patient's blood.

Prof Isaacs explained there are different types of cells that come together, rather like an army of soldiers, to attack an infection or disease.

These take instructions from the white blood cells known as dendritic cells, which he refers to as the "generals" of the immune system.

When these generals sense danger they become excited and send out the attack signal, but when there is no danger detected they remain calm and instruct the army to ignore healthy tissues.

When this goes wrong it causes diseases like rheumatoid arthritis.

Over the course of a week the patient's white blood cells are grown in the lab and trained to resemble the "calm" generals so that, when given back to the patient, they command the soldiers to stop attacking the patient's joints.

"In time, this treatment could provide significant benefits to people living with rheumatoid arthritis by 'switching off' the disease," Prof Isaacs explains.

Among the estimated 450,000 people in England who live with the condition is 70-year-old former nurse Ms Robson. She wakes up every morning to pain.

Before she was diagnosed she would put her hands in packets of frozen peas in an effort to find some relief.

She now takes immunosuppressants, which she says help a bit, but since being injected with the retrained white blood cells she believes she is in less pain.

"Is this just me hoping it is? But realistically I do think it is better," she says.

"If this trial works to switch off rheumatoid arthritis that would be wonderful.

"It's a privilege to be part of something that is actually quite a leap forward - if they get it right."

The outcome of the Newcastle work is being widely monitored as it could have huge implications for the 18 million rheumatoid arthritis patients worldwide.

Prof Isaacs said, if its successful, the research could also have implications for other autoimmune diseases such as diabetes or multiple sclerosis.

"It's an area of research that we describe as re-education of the immune system.

The first two trials are small - in total about 32 patients have been involved - and more research is needed, but if it shows signs of success another, larger trial will follow.

Even if all goes to plan and the treatment is shown to re-educate the immune system, it may still be another five to 10 years before patients are able to access it.

But Prof Isaacs, who has dedicated his career to the condition, said it would make him and his team immensely proud to have developed the treatment.