How quiet seaside town became export battleground

PA Media

PA MediaIt is hard to imagine Brightlingsea as anything but a quiet seaside town. But for 10 months in 1995 it became a very different place.

The town was thrust into the spotlight in January 1995 when farmers and exporters wanted to use the port to ferry live sheep and calves to Europe to be slaughtered – a practice that was banned last year.

Animal rights campaigners and police clashed on an almost daily basis. Police were drafted in from elsewhere in the country and hundreds of arrests were made.

What happened?

Brightlingsea is on the coast of north-east Essex, nestled between Colchester and Clacton-on-Sea.

But from the early hours of 16 January 1995, the morning after animal rights campaigners met at the town's community centre, all eyes were on Brightlingsea.

The unrest came to an end that October, when exporters, including Roger Mills, from Framlingham in Suffolk, who had sought injunctions against several protesters, decided to stop using the port because of the delays they had faced.

The press dubbed it the "Battle of Brightlingsea", and 30 years since it started, the BBC has taken a look back on what happened with people who were there.

The activist

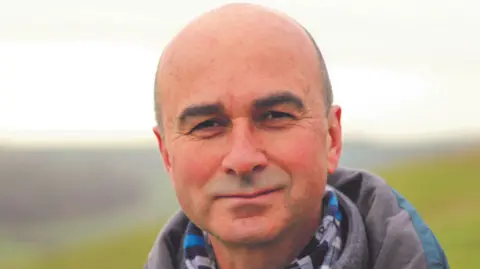

Compassion in World Farming

Compassion in World FarmingNow the chief executive of the animal welfare charity Compassion in World Farming, Philip Lymbery is as passionate about animal rights as he was 30 years ago. He told the BBC why protests broke out in towns like Brightlingsea.

"Public protests meant the big ports like Dover stopped having animals exported through them.

"The major ferry companies pulled out of exporting live animals, which displaced this cruel trade into small ports like Brightlingsea, Shoreham, and even Coventry Airport where calves were being flown out to the continent.

"It brought the trade into the public eye because, all of a sudden, these truckloads of living creatures, peering out with their frightened eyes, were driving past people's homes and down the High Street of places like Brightlingsea.

"This trade was suddenly in people's faces – ordinary people who care for animals and are animal lovers and they came out with a natural reaction which was: 'This trade is archaic. This trade is cruel and it should be banned.'

"I came to Brightlingsea to support the local uprising. The protests were so vibrant and so loud and so clear that it sent a message to the government that this trade had to be stopped."

The politician

Elliot Deady/BBC

Elliot Deady/BBCAfter more than 30 years in Parliament, Sir Bernard Jenkin is a familiar face on the Conservative backbenches. But in 1995, three years after he was first elected as the MP for the former North Colchester constituency, Sir Bernard told the BBC he never imagined what unfolded on his doorstep.

"People started writing to me about the trucks with live animal exports coming through and I looked into that and I wrote to the government, but I was told at the time it was fundamental to our membership of the European Union.

"Every time a convoy of trucks came through, they had to be accompanied by police walking each side, in front, and behind and there were crowds of people trying to slow the traffic down.

"There was a very combative atmosphere.

PA Media

PA Media"I attended a meeting at the community centre with hundreds of people and everyone wanted it to stop, whether they were part of the protest or not.

"It was raised at Prime Minister's Questions; it was debated. I actually took forward a bill to ban live exports and to exempt UK law from the European Union law but that didn't get anywhere because the government would not support it.

"I did something I'd never done before. I wrote to every single household in Brightlingsea to explain what I was doing and that got a very warm response because people realised I was doing my best, even though there was nothing I could do."

The reporter

Rupert Jones admits Brightlingsea "wasn't really on my radar" when he was reporting for the local newspaper, the Evening Gazette, until the protests started.

"There was only one main street that the lorries could go down. I remember people sitting in the road, people had placards, and you could get really close to the lorries.

"You probably could have reached out and touched the calves. That's a fairly heart-rending thing because you know where they're going.

"The thing that really struck me, and probably a lot of people, is that I imagined very militant protesters… but what was so interesting about the Brightlingsea protests was this was normal, local people.

"A lot of the protesters were women and there were a lot of older people. It made for a really interesting dynamic in terms of the policing because they weren't 'troublemakers'. Some of these people were the epitome of law-abiding people.

"It all ended very quickly. I think there was a very quick decision and I seem to recall it all fizzling out fairly fast.

"I think it came down to the fact the exporters decided it was too much aggravation and costing them too much money."

Follow Essex news on BBC Sounds, Facebook, Instagram and X.