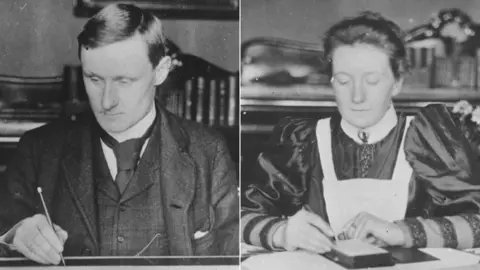

The brother and sister who tried to pioneer flight

Philip Jarrett

Philip JarrettPowered flight - one of the defining inventions of the 20th Century - was achieved in the US but, if not for a tragedy exactly 125 years ago, it could have been very different.

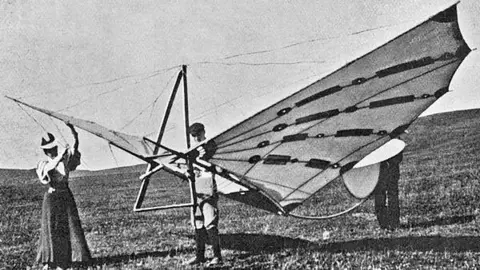

As aviation pioneer Percy Pilcher soared into the air above Leicestershire, watched by his sister and a group of potential investors, it seemed like the dream of powered flight was within their grasp - but then there was the loud crack of breaking wood.

Percy's journey to this point began in earnest as he honed his engineering skills in Victorian Britain's powerful navy.

But not content with ruling the waves, Percy, along with his older sister Ella, wanted to take to the skies.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPercy's biographer Philip Jarrett said: "Ella said he was fascinated by flight from an early age.

"And he, on long navy voyages, watched the birds like the albatross just ride the winds, seemingly without effort.

"But building something to carry a man was anything but effortless.

"There were no textbooks, no calculations or examples, they were, both literally and figuratively, stepping into thin air."

Philip Jarrett

Philip JarrettThe era was marked by an atmosphere of cooperation between pioneers.

Percy corresponded with fellow enthusiasts around the globe including Lawrence Hargrave in Australia, Octave Chanute in the US and Otto Lilienthal in Germany.

Lilienthal freely shared his breakthrough of the aerofoil, the curved surface which produced more lift than drag, which is fundamental to building a successful wing.

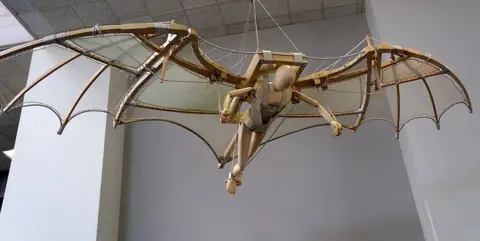

Fired with enthusiasm, Percy designed a series of gliders, which he called "soaring machines", built out of sailcloth, bamboo and piano wire.

Philip Jarrett

Philip JarrettDuring long hours in rented houses, university rooms and draughty barns, Ella used her sewing skills to create sweeping wing surfaces, carefully engineered to the tolerances Percy required.

Aviation historians say this probably makes her the first woman to be involved in the construction of fixed wing aircraft.

Filmmaker and historian Lily Ford said: "This kind of flying had seen centuries of failure and was kind of seen by some as quite ridiculous and they thought it would never happen.

"And even the chair of Natural History at Glasgow University, Lord Kelvin, who actually was a kind of sponsor of Percy Pilcher, said in 1896 - so this was after Percy and Ella were already experimenting - that he had no faith in flying by any other means [than balloon].

"So I think having somebody as a kind of accomplice, a collaborative, supportive person who believed in you, who believed that you could do it and who was totally prepared to roll up their sleeves, was a huge help to Percy."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPercy conducted a series of increasingly ambitious - and therefore dangerous - test flights in Glasgow and Kent.

The risks of operating at the very edge of technical knowledge were emphasised in 1896 with Lilienthal's death during an experimental flight.

But as Percy achieved greater distances - up to 250m (820ft) in 1897 - his reputation grew.

Mr Jarrett said: "He worked through ideas via a series of increasingly sophisticated designs with names like the Bat, Beetle and Hawk.

"He was dogged in working on problems until he had a solution."

Philip Jarrett

Philip JarrettDuring one of these tests, Ella agreed to be strapped in, so becoming the first female glider pilot in the UK, said Dr Ford.

She added: "She managed publicity. She sent people photographs. She may well have organised the photographs to be taken in the first place.

"She's in all the photographs, which is a wonderful thing.

"So she was really his collaborator, but because of how things were for women at that point, there just wasn't scope for her to be seen as a technological pioneer.

"There was no mould that she could fit in."

But Percy knew the real prize was powered flight, not gliders. This had become a serious possibility with the development of the internal combustion engine.

Mr Jarrett said: "Pilcher initially simply put an engine in the Hawk glider.

"But the extra weight meant he needed bigger wings - but this meant more superstructure, which meant yet more weight. He found himself in a vicious circle.

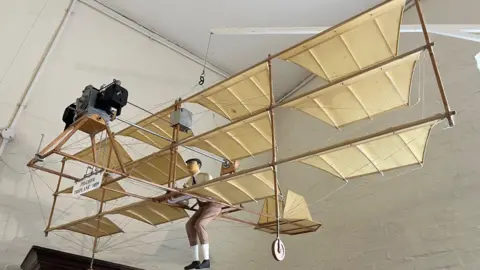

"Then appeared a letter from Octave Chanute which detailed the use of multiple small wings stacked on top of each other.

"Percy had a way forward and began work on an entirely new aircraft."

After constructing the triplane itself and having an engine built to go in it, Percy, again accompanied by Ella, gathered potential investors at Stanford Hall on 30 September 1899 for what promised to be the first powered flight in history.

After years of struggle, all the Pilchers needed was a fair wind and some luck. But they were to get neither.

Greg Wurr, a guide at the hall, said: "There were some important people present, including an MP, but shortly before the first demonstration of the triplane, part of the engine broke.

"Percy didn't want to disappoint the crowd or lose the opportunity to impress, so he got the Hawk out instead.

"It was a damp, blustery day and the Hawk was hard to handle but Percy got it into the air.

"As he was getting some height, part of the tail broke away and it plunged to the ground.

"Percy was badly injured and died at the hall three days later, aged just 32, with Ella by his side."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesWithin weeks of Percy's death, Ella, who had worked so hard and so closely with her brother, left England, sailing to South Africa to work as a nurse in the Boer War.

She continued to promote her and Percy's work, writing to the Royal Aeronautical Society, saying: "I should not like our name to be taken off your lists.

"As I always helped my dear brother in his experiments, I am able to take great interest in the subject."

Soon after, a vote at the society made Ella Pilcher its first honorary member.

The untested triplane was put into storage and, neglected, slowly fell to pieces and was lost.

The fate of the specially designed engine is also unknown.

So how close was Percy to achieving the centuries old dream of powered flight, a full four years before the Wright brothers claimed the prize?

In 2003 a team, including Mr Jarrett, pieced together the fragmentary evidence for Percy's triplane.

Dr Bill Brooks, an aircraft designer, was part of the project and actually piloted the reconstruction.

He said: "The basic configuration was remarkably good but there were a few things about it which weren't.

"There were cut-outs in the wings which reduced lift and his control system of just shifting his weight hanging from his arms was very limited.

"Also the power from his engine, which would have been between two and four horsepower, wasn't sufficient.

"So we had to surmise he would have recognised these and worked his way round them - the pace of development at the time was rapid.

"He had made more progress on a shoestring budget than people with big wallets had and, with time, I think he would have been the first, or among the first, to succeed."

After just two days of testing, the triplane achieved a flight time of one minute 25 seconds - beating the Wright brothers' best initial time by 19 seconds.

Follow BBC Leicester on Facebook, on X, or on Instagram. Send your story ideas to [email protected] or via WhatsApp on 0808 100 2210.