China is not backing down from Trump's tariff war. What next?

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe trade war between the world's two biggest economies shows no signs of slowing down - Beijing has vowed to "fight to the end" hours after US President Donald Trump threatened to nearly double the tariffs on China.

That could leave most Chinese imports facing a staggering 104% tax - a sharp escalation between the two sides.

Smartphones, computers, lithium-ion batteries, toys and video game consoles make up the bulk of Chinese exports to the US. But there are so many other things, from screws to boilers.

With a deadline looming in Washington as Trump threatens to introduce the additional tariffs from Wednesday, who will blink first?

"It would be a mistake to think that China will back off and remove tariffs unilaterally," says Alfredo Montufar-Helu, a senior advisor to the China Center at The Conference Board think tank.

"Not only would it make China look weak, but it would also give leverage to the US to ask for more. We've now reached an impasse that will likely lead to long-term economic pain."

Global markets have slumped since last week when Trump's tariffs, which target almost every country, began coming into effect. Asian shares, which saw their worst drop in decades on Monday after the Trump administration didn't waver, recovered slightly on Tuesday.

Meanwhile, China has hit back with tit-for-tat levies - 34% - and Trump warned that he would retaliate with an additional 50% tariff if Beijing doesn't back down.

Uncertainty is high, with more tariffs, some more than 40%, set to kick in on Wednesday. Many of these would hit Asian economies: tariffs on China would rise to 54%, and those on Vietnam and Cambodia, would soar to 46% and 49% respectively.

Experts are worried about the speed at which this is happening, leaving governments, businesses and investors little time to adjust or prepare for a remarkably different global economy.

How is China responding to the tariffs?

China had responded to the first round of Trump tariffs with tit-for-tat levies on certain US imports, export controls on rare metals and an anti-monopoly investigation into US firms, including Google.

This time too it has announced retaliatory tariffs, but it also appears to be bracing for pain with stronger measures. It has allowed its currency, the yuan, to weaken, which makes Chinese exports more attractive. And state-linked enterprises have been buying up shares in what appears to be a move to stabilise the market.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe prospect of negotiations between the US and Japan seemed to buoy investors who were fighting to claw back some of the losses of recent days.

But the face-off between China and the US - the world's biggest exporter and its most important market - remains a major concern.

"What we are seeing is a game of who can bear more pain. We've stopped talking about any sense of gain," Mary Lovely, a US-China trade expert at the Peterson Institute in Washington DC, told the BBC's Newshour programme.

Despite its slowing economy, China may "very well be willing to endure the pain to avoid capitulating to what they believe is US aggression", she added.

Shaken by a prolonged property market crisis and rising unemployment, Chinese people are just not spending enough. Indebted local governments have also been struggling to increase investments or expand the social safety net.

"The tariffs exacerbate this problem," said Andrew Collier, Senior Fellow at the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government at Harvard Kennedy School.

If China's exports take a hit, that hurts a crucial revenue stream. Exports have long been a key factor in China's explosive growth. And they remain a significant driver, although the country is trying to diversify its economy with high-end tech manufacturing and greater domestic consumption.

It's hard to say exactly when the tariffs "will bite but likely soon," Mr Collier says, adding that "[President Xi] faces an increasingly difficult choice due to a slowing economy and dwindling resources".

It goes both ways

But it's not just China that will be feeling the impact.

According to the US Trade Representative office, the US imported $438bn (£342bn) worth of goods from China in 2024, with US exports to China valued at $143bn, leaving a trade deficit of $295bn.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnd it's not clear how the US is going to find alternative supply for Chinese goods on such short notice.

Taxes on physical goods aside, both countries are "economically intertwined in a lot of ways - there's a massive amount of investment both ways, a lot of digital trade and data flows", says Deborah Elms, Head of Trade Policy at the Hinrich Foundation in Singapore.

"You can only tariff so much for so long. But there are other ways both countries can hit each other. So you might say it can't possibly get worse, but there are many ways in which it can."

The rest of the world is watching too, to see where Chinese exports shut out of the US market will go.

They will end up in other markets such as those in South East Asia, Ms Elms adds, and "these places [are dealing] with their own tariffs and having to think about where else can we sell our products?"

"So we are in a very different universe, one that is really murky."

How does this end?

Unlike the trade war with China during Trump's first term, which was about negotiating with Beijing, "it's unclear what is motivating these tariffs and it's very hard to predict where things might go from here," says Roland Rajah, lead economist at the Lowy Institute.

China has a "wide toolkit" for retaliation, he adds, such as depreciating their currency further or clamping down on US firms.

"I think the question is how restrained will they be? There's retaliation to save face and there's pulling out the whole arsenal. It's not clear if China wants to go down that path. It just might."

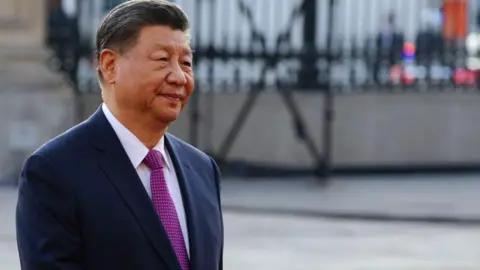

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSome experts believe the US and China may engage in private talks. Trump is yet to speak to Xi since returning to the White House, although Beijing has repeatedly signalled its willingness to talk.

But others are less hopeful.

"I think the US is overplaying its hand," Ms Elms says. She is sceptical of Trump's belief that the US market is so lucrative that China, or any country, will eventually bend.

"How will this end? No-one knows," she says. "I'm really concerned about the speed and escalation. The future is much more challenging and the risks are just so high."