Nasa makes history with closest-ever approach to Sun

NASA

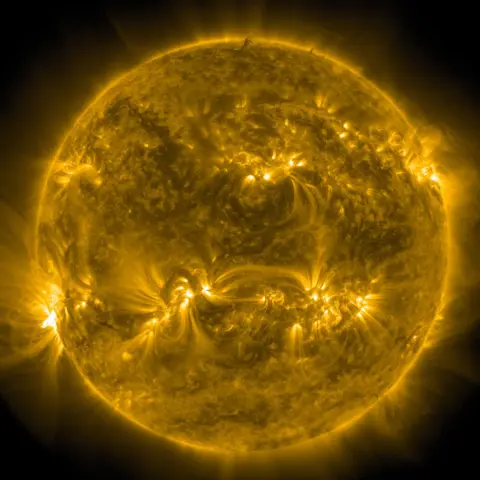

NASAA Nasa spacecraft has made history by surviving the closest-ever approach to the Sun.

Scientists received a signal from the Parker Solar Probe just before midnight EST on Thursday (05:00 GMT on Friday) after it had been out of communication for several days during its burning-hot fly-by.

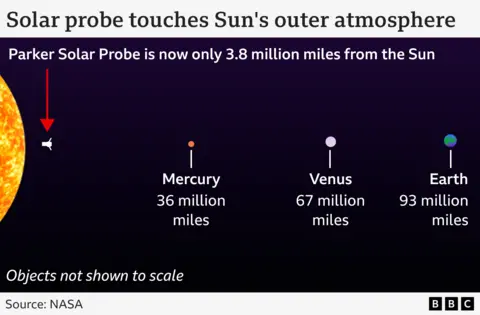

Nasa said the probe was "safe" and operating normally after it passed just 3.8 million miles (6.1 million km) from the solar surface.

The probe plunged into our star's outer atmosphere on Christmas Eve, enduring brutal temperatures and extreme radiation in a quest to better our understanding of how the Sun works.

Nasa then waited nervously for a signal, which had been expected at 05:00 GMT on 28 December.

Moving at up to 430,000 mph (692,000 km/h), the spacecraft endured temperatures of up to 1,800F (980C), according to the Nasa website.

"This close-up study of the Sun allows Parker Solar Probe to take measurements that help scientists better understand how material in this region gets heated to millions of degrees, trace the origin of the solar wind (a continuous flow of material escaping the Sun), and discover how energetic particles are accelerated to near light speed," the agency said.

Dr Nicola Fox, head of science at Nasa, previously told BBC News: "For centuries, people have studied the Sun, but you don't experience the atmosphere of a place until you actually go [and] visit it.

"And so we can't really experience the atmosphere of our star unless we fly through it."

NASA

NASAParker Solar Probe launched in 2018, heading to the centre of our solar system.

It had already swept past the Sun 21 times, getting ever nearer, but the Christmas Eve visit was record-breaking.

At its closest approach, the probe was 3.8 million miles (6.1 million km) from our star's surface.

That might not sound that close, but Dr Fox put it into perspective. "We are 93 million miles away from the Sun, so if I put the Sun and the Earth one metre apart, Parker Solar Probe is 4cm from the Sun - so that's close."

The probe endured temperatures of 1,400C and radiation that could have frazzled the on-board electronics.

It was protected by an 11.5cm (4.5in) thick carbon-composite shield, but the spacecraft's tactic was to get in and out fast.

In fact, it moved faster than any human-made object, hurtling at 430,000mph - the equivalent of flying from London to New York in less than 30 seconds.

Parker's speed came from the immense gravitational pull it felt as it fell towards the Sun.

PA Media

PA MediaSo why go to all this effort to "touch" the Sun?

Scientists hope that as the spacecraft passed through our star's outer atmosphere - its corona - it will have collected data that will solve a long-standing mystery.

"The corona is really, really hot, and we have no idea why," explained Dr Jenifer Millard, an astronomer at Fifth Star Labs in Wales.

"The surface of the Sun is about 6,000C or so, but the corona, this tenuous outer atmosphere that you can see during solar eclipses, reaches millions of degrees - and that is further away from the Sun. So how is that atmosphere getting hotter?"

The mission should also help scientists better understand solar wind - the constant stream of charged particles bursting out from the corona.

When these particles interact with the Earth's magnetic field the sky lights up with dazzling auroras.

But this so-called space weather can cause problems too, knocking out power grids, electronics and communication systems.

"Understanding the Sun, its activity, space weather, the solar wind, is so important to our everyday lives on Earth," said Dr Millard.

NASA

NASANasa scientists faced an anxious wait over Christmas while the spacecraft was out of touch with Earth.

Dr Fox had been expecting the team to text her a green heart to let her know the probe was OK as soon as a signal was beamed back home.

She previously admitted she was nervous about the audacious attempt, but had faith in the probe.

"I will worry about the spacecraft. But we really have designed it to withstand all of these brutal, brutal conditions. It's a tough, tough little spacecraft."

(Additional reporting by Tim Dodd)