One year on: Did democratic opposition in Russia die with Alexei Navalny?

BBC

BBCA year after Alexei Navalny's suspicious death in a Russian prison, his supporters have been helping choose a headstone for his grave in Moscow.

"It will be a place of hope and strength for all those who dream of the wonderful Russia of the future," says the opposition politician's widow, Yulia Navalnaya, quoting one of his best-known phrases.

Revealing her shortlist of designs in a video last week, she hoped the grave would become somewhere that those who oppose Vladimir Putin go "to remember they are not alone".

Navalnaya now lives abroad, facing arrest if she were to return to Russia.

Her words capture just how far ambitions have shrunk.

Getty Images

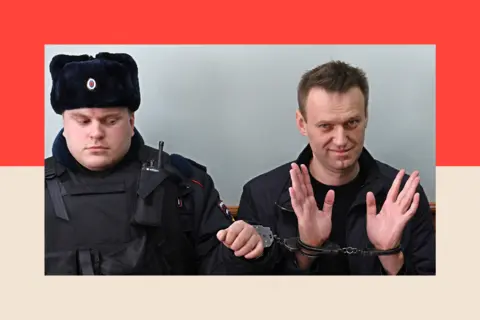

Getty ImagesFor years, Alexei Navalny was Vladimir Putin's biggest political rival: charismatic and courageous. Today, even his lawyers have been jailed as "extremists" and a huge number of supporters have fled Russia for safety. Those who've stayed are mostly scared into silence.

Now Vladimir Putin, far from being defeated by a ruinous war on Ukraine, looks like dictating the terms of a peace deal there alongside Donald Trump.

So did Russia's democratic opposition and its dream of change die in an Arctic prison yard with Alexei Navalny?

Squeezing Russia's democratic life

Ksenia Fadeeva was serving a nine-year sentence when the TV in her cell announced that Navalny was dead. He had collapsed in prison on his daily walk.

Getty Images

Getty Images"I was in a stupor; I couldn't even speak," the activist remembers. "It was a nightmare."

Ksenia was a political prisoner herself, labelled an "extremist" for her previous links to Navalny. She managed his HQ in her Siberian hometown, Tomsk, when Navalny tried to run against Putin in the 2018 presidential elections. He was blocked.

Back then, Ksenia showed me how her car had been coated in paint and had its tyres slashed. On another day the door of her flat was sealed shut with foam glue, trapping her inside.

The young activist shrugged all this off. It came with the territory.

Reuters

ReutersAt that point, Putin had been squeezing the democratic life out of Russia for close to two decades. He'd moved from controlling the media to rigging elections and punishing protest. Then came poisoning and political assassination.

This month also marks 10 years since Boris Nemtsov, another powerful voice of opposition, was killed. He was shot in the back close to the red walls of the Kremlin.

Russia had annexed Crimea illegally the previous year and Putin's approval rating was still riding a wave of toxic nationalism. Critics like Nemtsov were publicly slurred as traitors.

The politician's lifeless body, sprawled beneath fairy lights in the colours of the Russian flag, marked the start of a dark new era.

Opposition criminalised and exported

Navalny did his best to breathe new life into Russia's beleaguered opposition.

A master of social media and of the anti-corruption agenda, he had real appeal, especially to a younger crowd.

But in 2020 he was poisoned with a Novichok nerve agent and almost died.

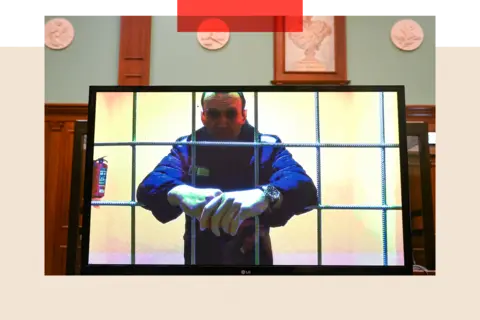

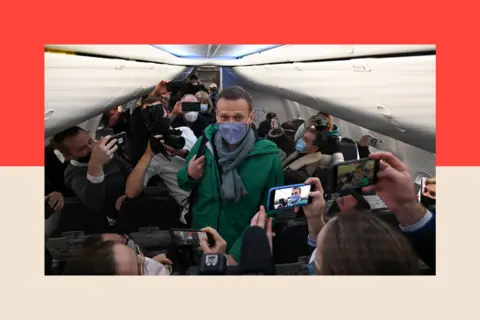

Getty Images

Getty Images"I knew they could put you in prison, break up protests with batons, invent criminal charges. But poisoning with a chemical weapon?" Ksenia Fadeeva remembers her shock at the attack. "I thought there were some brakes on the system, but I was wrong."

When Navalny returned from treatment abroad, he was arrested at the airport.

He would never walk free.

In that environment, the lack of overt opposition within Russia is hardly surprising.

"I don't think there is any country in the world where many would risk years in prison for speaking out," Vladimir Kara-Murza, a prominent activist, wrote to me once from his own jail cell.

Sentenced to 25 years for condemning Russian war crimes in Ukraine, Kara-Murza smarted at criticism of Russians for failing to stand up to Putin more firmly and failing to stop the full-scale invasion.

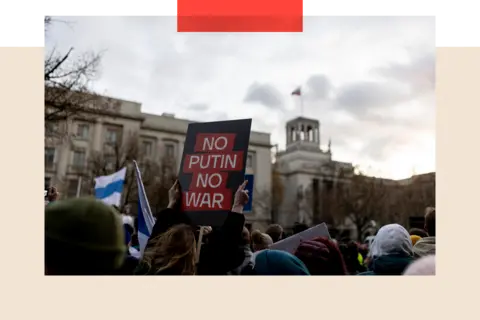

Navalny was already in jail. A spattering of anti-war protests was quickly stamped out.

"Inside Russia, it's not a matter of there being no one with the charisma of Navalny," Tatiana Stanovaya, senior fellow at the Carnegie Russia-Eurasia Centre says, explaining the lack of any new leader since his death.

"We're talking about the complete criminalisation of opposition."

Getty Images

Getty ImagesLast August, Vladimir Kara-Murza and Ksenia Fadeeva were taken from their cells and forcibly deported as part of a giant exchange of prisoners.

The Kremlin was exporting dissent.

By then, Navalny was dead.

Ksenia believes that had he lived, even from abroad Navalny could have made a difference. "Things would have been different if they'd let Navalny out in a swap. His voice would have been loud, the opposition would have had more influence", she says.

"In today's tough conditions, I don't know where you find another leader like Navalny."

In a holding pattern

His team haven't stopped working in exile. One half lobbies Western governments for more effective sanctions, the others try to smash through the wall of Russian propaganda with exposés of Putin's entourage.

Their latest film targets a powerful ally of Putin, Igor Sechin, arguing that Putin is only pretending to "make Russia great" while he and his cronies plunder the country's wealth.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSuch investigations used to spark real-life protests. Now those viewers still inside Russia can only watch via VPN and most dare not post comments.

"You can get a criminal charge now, just for lifting a finger," Ksenia Fadeeva points out, although the latest film was seen almost two million times in 10 days.

Ksenia is sure most of that audience is in Russia.

"People haven't changed their views, they're still there. They definitely read and follow and watch," she says. "But they can't protest. They're just surviving."

That's a word I hear often from activists: they describe Russian opposition forces in a kind of holding pattern.

"We can stick to our basic pro-democracy values and try to keep people safe for the future Russia," Anastasia Burakova argues, and her own "Ark" project tries to do just that.

"But nobody knows how to successfully finish this dictatorship."

Failing to convince

But is there actually demand for that?

"Imagine asking: 'Do you support Vladimir Putin or do you want to go to jail for 15 years,'" says Ksenia Fadeeva, mocking the value of conducting polling in an authoritarian regime.

Others believe researchers do still have ways to take the social pulse, and they confirm that it's not set racing by Yulia Navalnaya and co.

Reuters

ReutersNavalny's widow has moral authority but nowhere near his political skills.

"All these… liberal figures have extremely low approval ratings," says academic Tatiana Stanovaya. Instead, she detects a consolidation of support for the Kremlin which she links to a surge in Ukrainian drone strikes on Russia.

"People see that we are very vulnerable and they have to choose the strongest player to rely on," the analyst explains. "It's not because they like Putin or consider him a positive hero. It's because he can protect Russia in a very hostile environment."

No matter that Putin created that environment himself by going to war.

It helps that Donald Trump now appears to be siding with Moscow: the US president once said he "understood" Russia's veto on Ukraine joining Nato. He now seems to have conceded that major condition, even before any peace talks.

"I think the war has further entrenched anti-Western sentiment," Dr Jade McGlynn of King's College suggests. "I also don't really see evidence there's even a strong minority of Russians who are desirous of a liberal, Western-allied type of democracy."

"I think the liberals… ultimately failed to convince."

There's a whole lot wrapped up in that line, including the economic pain and massive corruption Russians experienced as the USSR fell apart. It all helped make democracy a dirty word.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesFor years, state TV has also been shouting into every living room that critics of Russia are its enemies, and Western agents.

"The Kremlin plays on a real fear, ingrained in Russian minds, that the West has been trying to ruin Russia, weaken and divide it," Tatiana Stanovaya argues.

"There is good soil for the Kremlin to work on."

Divided dissent

Opposition forces are also deeply divided.

Fierce rivalries and personality clashes that go back many years have intensified in exile and now frequently erupt into vicious and very public fights.

"We can debate after democracy in Russia begins, but for now we have the same goal and the same enemy: he's in the Kremlin," Anastasia Burakova voices the frustration of many that such scrapping is a dangerous distraction.

That division is part of why Jade McGlynn thinks Russia's exiled activists might better be called "dissidents" than a political opposition.

"Politics is about practicality, otherwise you are a philosopher," she argues – and challenging those in power is impossible in Russia right now.

Reuters

ReutersAnastasia Shevchenko agrees. But just surviving Putinism isn't good enough for her. "I hate when people still talk about the 'beautiful Russia of the future'," the Russian activist quoted Alexei Navalny, when we met in a Kyiv coffee shop last month.

"You can't be happy next to destroyed cities where so many people were killed."

Other opposition figures insist on referring to "Putin's war", to suggest that most Russians are against the invasion - which infuriates Ukrainians.

"I think to claim that it's one man's war when you have 600,000 troops there and over three million in the defence industry, not including all the propagandists, is not convincing," Jade McGlynn is firm.

Other ways to help

But Anastasia Shevchenko struggles to focus on anything else. Whilst change within Russia remains "very far away", she sees Ukraine is in trouble now and she can help.

She's become a one-woman telephone exchange for Ukrainian soldiers held captive in Russia: prisoners of war, who can't call Ukrainian numbers from Russian jails, dial Anastasia's Russian mobile. She gets their mother or wife on another line and places the phones together so they can talk.

"If you can help Ukraine, you should do that," she believes. "But we Russians are focused only on Russia and I don't understand it."

Still readjusting to life out of prison, and out of her country, Ksenia Fadeeva has shifted her own focus from politics to human rights for now, helping political prisoners.

"I still believe Russia has every chance of becoming a normal, free, peaceful European country," Ksenia Fadeeva insists. "But the regime is far harsher now, more authoritarian."

Anastasia Shevchenko agrees, though she remembers the collapse of the USSR and concedes that history is unpredictable.

"You never know what happens. Things can change quickly. So you have to be ready."

But ready for what?

Spectre of nationalism

The idea of Russia leaping from Putinism to liberal democracy looks less likely than ever.

Jade McGlynn sees no prospect at all, unless the vision that led to the invasion of Ukraine - "this imperial, chauvinist vision of Russia" – is defeated.

Getty Images

Getty Images"I think that's where we will see real opposition," she thinks. "From disgruntled nationalists," especially in a country with tens of thousands of war veterans and all their trauma.

"What will the authorities 'sell' to the people then? What idea?," Ksenia Fadeeva wonders, when the war is finally over.

All agree the political repression will remain intense. As the analyst Tatiana Stanovaya puts it: "The state, especially the repressive apparatus, do not have the skills to retreat."

On Sunday, Navalny's supporters plan memorials from Argentina to Australia to mark the anniversary of his death. In Moscow, some will visit his graveside. A few may dare to chant for change. But most of all, those who still cling to the dream of a democratic Russia will be checking who else is still out there. Still waiting.

Top image: Getty Images

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.