Country park's huge role in D-Day airborne assault

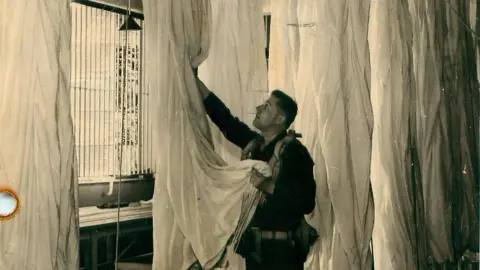

Airborne Assault Museum / ParaData.org.uk

Airborne Assault Museum / ParaData.org.ukHours before the warships began their bombardment and the landing craft motored towards the beaches on 6 June 1944, British troops had already landed in northern France.

Their mission was to capture bridges and German machine gun nests.

And while the 133,000 men involved in D-Day came from all over Britain, the Commonwealth and the USA, all the British paratroopers who landed in the early hours had one thing in common.

They were all trained in Cheshire.

Specifically, the men of the Sixth Airborne Division were trained in the grounds of the country house at Tatton Park, near Knutsford, and the small airport in the Ringway parish of the county – which would later become the Manchester Airport known today.

The role of the stately home, and the wider east Cheshire countryside in the preparations for Operation Overlord, is not widely known.

But it is a story pivotal to the outcome of World War Two.

Airborne Assault Museum / ParaData.org.uk

Airborne Assault Museum / ParaData.org.ukThe sight of thousands of parachutes unfurling in the skies over the Low Countries of Europe terrified the population of the Netherlands in 1940.

The German invasion of Holland was one of the first mass airborne assaults of the war.

While it has been said that neither the commanders of the British Army nor the Royal Air Force took any particular interest in developing parachute regiments, the method of invasion captured the imagination of British prime minister Winston Churchill.

And before long the spectacle of parachute troop deployments would soon become a familiar one in the skies over Cheshire.

Manchester's Ringway Airport became the base for the Parachute Training School (PTS) in June 1940, but when it became apparent that it was too busy for the troops to land there, an approach was made to the owner of nearby Tatton Hall and Park.

Maurice Egerton, the 4th baron Egerton and the owner of the hall, was a keen aviator who had been friends with the pioneers of flight, the Wright Brothers. He offered up the grounds of his country home as a landing ground for the paratroopers.

According to contributors to a new book, Airborne Tatton, produced by the Manchester Branch of the Parachute Regimental Association, about 60,000 troops would make about 400,000 jumps there during the war years.

Airborne Assault Museum / ParaData.org.uk

Airborne Assault Museum / ParaData.org.ukThe jumps were made from barrage balloons whose mooring points can still be seen in the park to this day, and then later from Whitley bombers and Dakota transport planes.

In total, 46 men were killed during the training, and many others were injured.

Evelyn Waugh, who was a captain in the Special Operations Executive (SOE), broke his leg on his second jump, which rendered him unfit for active duty. He spent much of the rest of the war at a desk, during which he penned the novel Brideshead Revisited. Tatton Hall is said to have been an inspiration for descriptions of the fictional stately home that gives that book its name.

Women were also among those who were parachute trained at Tatton, including Odette Hallowes, a member of the SOE who dropped into occupied France in 1942 to conduct espionage and sabotage operations. She was captured in 1943 along with her husband, Peter Churchill, and saw out the war at Ravensbruck concentration camp.

Airborne Assault Museum / ParaData.org.uk

Airborne Assault Museum / ParaData.org.ukThe assault on Normandy on 6 June 1944 would be made by air, land and sea. But the opening gambit of the invasion was airborne. While warships and warplanes would attempt to soften up German fortifications, it was vital that the advance inland from the beaches had the maximum chance of success.

And to achieve that, the paratroopers trained at Tatton Park and Ringway would be vital. Thousands of them jumped from Dakotas just after 00:00 on 6 June, landing behind the lines and attempting to capture key positions, and all of the British contingent had learned how to make their landings in simulations in the Tatton Park.

Those who did not land by parachute instead touched down in gliders that had been towed behind planes, in techniques mastered at Ringway.

A memorial obelisk stands in Tatton Park on the edge of the drop zone, dedicated to all who trained there between 1940 and 1945.

It reads: "This stone is set in honour of those thousands from many lands who descended here in the course of training given or received for parachute service with the Allied Forces in every theatre of war."

Listen to the best of BBC Radio Manchester on Sounds and follow BBC Manchester on Facebook, X, and Instagram. You can also send story ideas to [email protected]